C.5 Multinational crews and multiculturalism

- Details

ROAR HANSEN, ANETTE FAGERTUN

Shipping: a global, multinational and multicultural industry

The shipping industry, and therefore the workplace of seafarers, has during the past decades increasingly become a global entity. This reality has brought fundamental changes to the maritime industry in terms of company structure and ownership, trade, staffing policies, tempo and work conditions.

Transforming structures have subsequent and far-reaching implications for the health and wellbeing of seafarers and has also brought forth potential challenging issues as seafarers of many nationalities and cultures live and work together for prolonged periods of time.

Serving as an example, the Norwegian maritime sector has for generations been made up of Norwegian ship owners and companies, shipyards, supply chains and seafarers, and the industry has played a significant role for both the national economy and the imagination of nationhood. In the wake of the Norwegian International Ship Register (NIS) in 1987, the “Norwegian” merchant fleet is today multinational, manned by 20 000 seafarers from the Philippines (about 45 % of the total), 10 000 from Eastern Europe, 6000 from India, 5-6 000 Norwegians and approximately 3000 seafarers from other countries worldwide1.

Besides bringing people from every corner of the world together and creating job opportunities globally, a key organizing principle for labour policy in today’s globalized world is flexibilization. This means that informality and competition have become the dominant modes of employment2,15, giving rise to a rapid increase in exploitative forms of wage work, often conceived of as ‘precarious labour’, and the maritime sector is no exception. Increased competition, and a focus on reducing labour costs, have created new criteria for inclusion and exclusion, which tend to politicize notions of culture and multi-nationality.

The concept of multiculturalism refers to a political philosophy that approaches diversity by emphasising equal rights and opportunities for all citizens, and a positive valuation of ethnic, religious and cultural differences in a society16. It differs from ‘diversity politics’ where such differences might be acknowledged but not approached in the same manner. Multiculturalism may serve as a useful guiding ideal for both thinking and practicing within multinational contexts.

What is culture?

Linguistic and psychological approaches dominate the research into intercultural communication. These approaches focus on the breakdown or misunderstandings in encounters, or communicative behavior, between people in situations of cultural diversity. Intercultural communication studies commonly classify culture “on the basis of nationality or pan-national traits…or more generally still as Western (individualist) and Eastern (collectivist)”3, p150. Geert Hofstede highlights generalized differences between national cultures and regional different worldviews4. In line with Durant & Shepherd3, we encourage caution of such arguments, both because they may contribute to simplify complex relationships between nations and cultures and because they may encourage cultural stereotypes and stigmas that can have a derogatory effect on people affected by their use, for example onboard a vessel.

Culture is a complex concept defined in many different ways. Common for all ‘definitions’ is that culture is about something a group of people share, it is collective, and it has symbolic, structural, practical and material dimensions. The concept of culture comes from a time in history dominated by colonialism, strong beliefs in race and evolution, and the emergence of strong nation states. It was often used to mean heritage, as a people’s, a nation’s or a tribe’s distinct, inherited and unwavering ways of being.

Clifford Geertz described culture as “webs of meaning within which people live”5, p3 that include values, attitudes and beliefs, as well as practices and structures. Numerous studies of human culture have shown that academic and political assumptions about a direct correlation between a people/nation and a culture are misguiding. Culture deals both with similarities and differences in ways of being and perceiving the world, and such values and beliefs may both differ within a nation/people, and may be shared across assumed cultural and geographical boundaries. Roger Keesing understands culture as “systems of knowledge” that shape and constrain humans in their interactions. As a knowledge-system, culture is socially produced and unequally distributed. Culture does not only produce systems of meaning along national demarcations, ‘it’ also positions individuals differently according to social categories such as gender, class, occupation and education6.

Structural and organisational factors

Work cultures, communication and safety are all social phenomena shaped and produced at a certain point in time, within specific social contexts and through specific social relations. They exist within specific structural frameworks that encompass both possibilities and limitations. Culture is not only heritage or nationality, culture must also be understood as always changing in the interface between knowledge, institutional conditions and individual experiences.

The maritime industry has undergone a great transformation during the last 40 years due to globalisation, technological innovation, increased competition and flexibilization of labour. Depending on trade segments, the size of crews on board has decreased by as much as 60%, some companies employ only top officers, both deck and engine, whilst crew and ratings are engaged through various, often short-term contracts involving manning companies and agents external to the ship owner. Several, usually western, companies have staffing policies restricting non-western mariners from climbing higher than to 2nd or 3rd officers. The length of work period differs greatly within the industry. In some companies, seafarers employed in the company work on board for 8-12 weeks and enjoy well regulated time on shore. Others sign 12 months contracts, with few if any guarantees for further employment, or paid time in between trips to sea8. In addition, the increasing globalization of the industry combined with an ongoing combat to reduce costs, have generated highly uneven and unfair wage regimes where non-western seafarers may only be entitled to 1/3 of the salary paid to western employees, for performing the same job9. Further information on the employment of seafarers is available in Ch. 4.1.

When considering the seafarer’s individual experience it is also important to keep in mind a key characteristic of migrant work, remittance, and, in the case of maritime work, the strong identity of being a seafarer. In the case of Filipino seafarers for example, the seafarers are both a product of and for their families10. As “family enterprises”, their individual professional careers are always interwoven with their families in terms of both obligation, sentiments, and financial contributions. In the Philippines, as in many countries in the Global South, education is expensive, and the task of educating a son to become a certified seafarer often involves substantial financial contributions from kin, godparents, family friends and more. Furthermore, in a global system of manning agents, international companies and tough competition, the most likely path towards a contract may involve many middle-men and favours. This generates a system of often life-long obligations of debt and repayment, as well as strong moral expectations for the seafarer to himself contribute to the education of others within this social network of payments and reimbursements. The importance of continued engagement, to never un-sign no matter what- guides many Filipino seafarer’s attitudes towards their job. Thus, the structural conditions shaping the seafarers ‘choices’ combined with the social obligations of the seafarer create a particular work situation that should be recognized when considering the workers’ health and wellbeing.

Culture and Medicine

Human beings’ understandings and expectations regarding health, sickness and cure vary greatly. Health and sickness bring together biological, cultural and individual processes.

Cultural values about “proper” treatment may be guided by efforts towards regaining balance (Ayurveda and Chinese medicine), fighting a virus (western biomedicine), or re-establishing good interpersonal relationship and avoiding conflicts (African and Asian folk medicine). Within strong religious belief systems, topics of sickness and health are subjected to ‘God’s will’, and in some parts of the world belief in magic, healers and luck are the driving forces behind sickness, health and cure.

Seafarer’s cultural beliefs, therefore, may, or may not, coincide with the current practice of maritime medical examinations and treatment. Eisenberg distinguishes between illness and disease to highlight this relationship, where the former refers to the individual experience of suffering while the latter to the medical experts’ diagnosis of this suffering11. The greater the difference between the explanatory models of patient and doctor, the less are the chances for compliance to the prescribed treatment. This situation is further highlighted on board where medical care is delivered by an officer with limited medical training. The officer may be of a different culture with a different understanding and expectation of health and sickness and of course, a different first language.

Seafarers are heavily overrepresented in terms of fatalities such as accidents, suicide, and psychological disorders 12. A majority of mariners report that they never or rarely get ashore during their work periods12,p2. Long contracts and working days in combination with the solitary nature of life at sea, makes it challenging to cope regardless of cultural background. However, for people from cultural backgrounds where being part of a larger, close community is important (kin, tribe, local community, family belonging), such illness is believed to be a natural consequence of being isolated from the required (and health- giving) social circumstances that generate wellbeing. If interpreted as solely deriving from individual pathology and treated only through individual intervention (medication), compliance to psychological support and treatment may be dramatically reduced. A mixed approach highlighting both the need to follow individual prescriptions, and to strengthen/re-engage social networks, for example, get in contact with relatives, visit fellow citizens/church congregation in the next port, etc., will most likely create a better outcome for both the patients and medical care givers.

Cultural awareness

Cultural awareness

The global variation in how people perceive and interpret their surroundings is enormous. It falls outside of the scope of this text to provide a detailed account of this matter. However, there are two general guidelines fostering multiculturalism and constructive multicultural interaction in multinational work places.

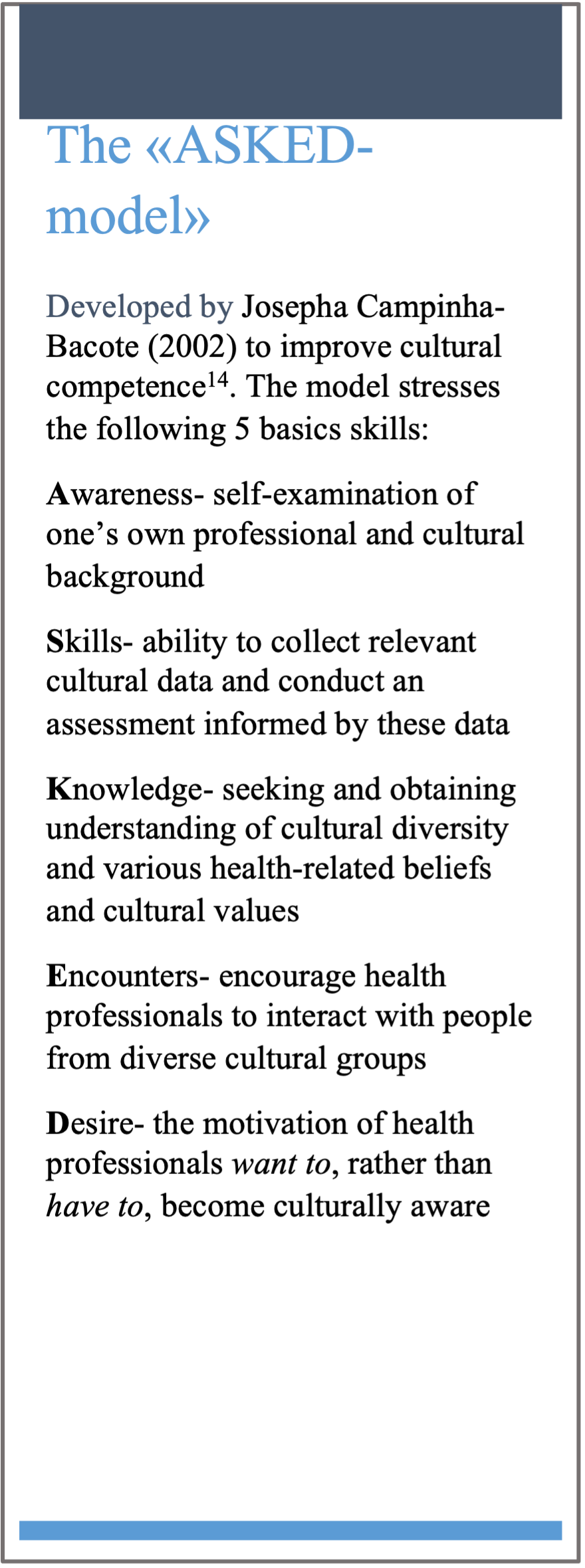

First, cultural competency is a key factor in establishing good communication across cultural horizons. At a basic level, this implies showing an interest in, and seeking knowledge of, peoples’ cultural background and sentiments. Besides broadening ones’ own horizon, the ability to engage in conversations showing knowledge of local/cultural issues are always experienced as respectful and trustworthy. For maritime health professionals cultural competency skills should be built and practiced to improve the quality and compliance of consultation and treatment.

Secondly, sickness and health are always culturally mediated and communicated. Benedicte Ingstad (2007) set out 4 different ways that culture mediates sickness (our translation) 13, p40

- through interpretation of symptoms

- by the way symptoms are communicated

- through ways of legitimizing sickness

- by (possibly) creating disease (culturally-bound syndromes)

The “ASKED-“model” presented here provides a good rule of thumb for effective interaction in a multicultural setting. As with much safety and competence work, it urges everybody to start with their own assumptions and values.

References

(1) Norwegian Shipowners Association 2009. Annual Report at https://rederi.no/globalassets/dokumenter/alle/arsrapporter/11-00646-2-2009-arsrapport-nr.pdf-215871_1_1.pdf retrieved October 19 2018

(2) Breman, J., & Van der Linden, M. (2014). Informalizing the economy: The return of the social question at a global level. Development and Change, 45(5), 920-940.

(3) Durant, Alan & Ifan Shepherd 2009. ‘Culture’ and ‘Communication’ in Intercultural Communication. European Journal of English Studies, 13:2, pp. 147 – 162.

(4) Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications.

(5) Ortner, Sherry (1994). Introduction, in The fate of Culture. Geetz and beyond, Sherry Ortner (ed.), pp. 1- 14. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

(6) Keesing, R. M. (1974). Theories of culture. Annual review of anthropology, 3(1), 73-97.

(7) Goffman, E. (1961). On the characteristics of total institutions. In Symposium on preventive and social psychiatry (pp. 43-84). Washington, DC: Walter Reed Army Medical Centre.

(8) Hansen, Roar, Gunnar M. Lamvik og John Meling 2001. «Barkada-rapporten:

Flerkulturelle utfordringer i moderne rederi- og skipsdrift». Report from a joint research project..

(9) Alderton, Tony, Michael Bloor, Erol Kahveci, Tony Lane, Helen Sampson, M. Zhao, M. Thomas, Nik Winchester, and Bin Wu. The global seafarer: Living and working conditions in a globalized industry. International Labour Organization, 2004.

(10) Lamvik, Gunnar M. (2012) The Filipino Seafarer: A life between sacrifice and shopping. Anthropology in Action, 19 (1):22-31.

(11) Eisenberg, Leon (1977). Disease and illness Distinctions between professional and popular ideas of sickness. Culture, medicine and psychiatry, 1(1), 9-23.

(12) International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assitance Network (ISWAN) (2015). Social isolation of Seafarers http://seafarerswelfare.org/news-and-media/latest-news/article-discusses-the-social-isolation-of-seafarers retrieved October 19 2018

(13) Ingstad, Benedicte (2007). Medisinsk Antropologi- en innføring. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

(14) Campinha-Bacote, J. (2002). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. Journal of transcultural nursing, 13(3), 181-184.

(15) ILO 2013, Caught at Sea. Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---declaration/documents/publication/wcms_214472.pdf, retrieved August 16 2018

(16) Bygnes, Susanne 2012. Ambivalent Multiculturalism. Sociology 47(1), pp. 126 – 141.

Cultural awareness

Cultural awareness