TIM CARTER

C.7.1 Introduction

Seafarers working at sea need to safely and effectively perform a wide variety of tasks. Most involve the seafarer receiving information about their surroundings, analysing it and then taking appropriate actions that usually require movement of their hands, limbs, head or body.

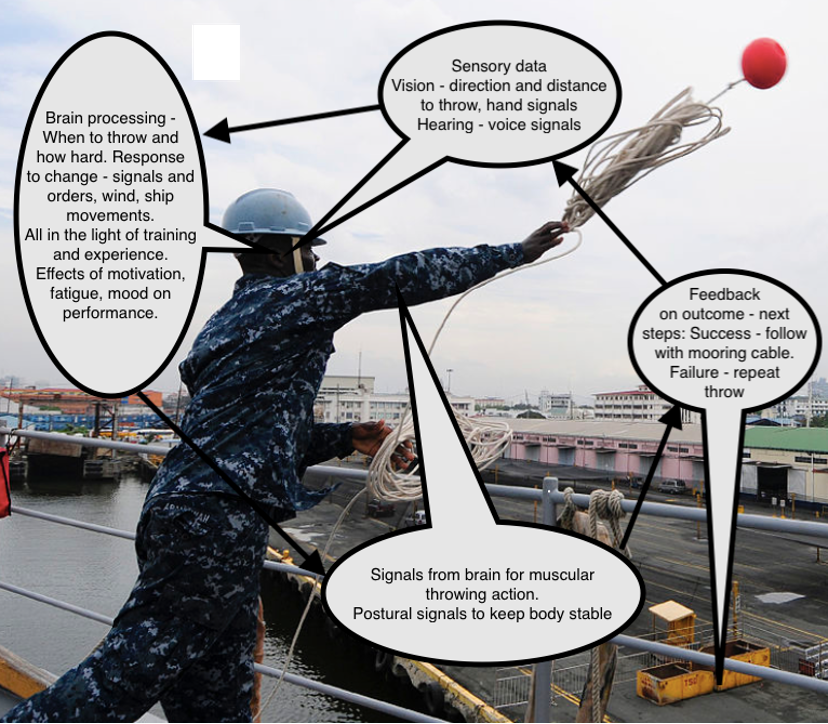

Fig 20.1 Information processing and actions throwing a mooring line

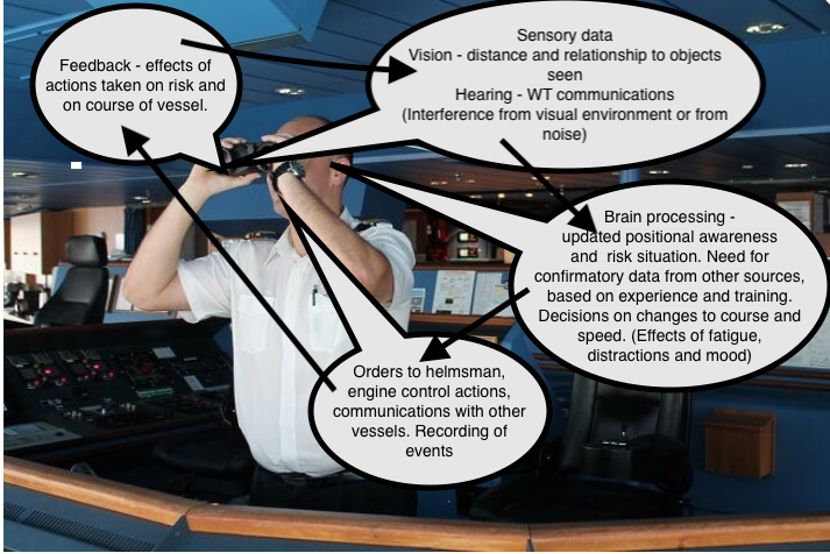

Thus performance depends on

- the sense organs, such as the eyes and ears to receive information

- the ability of the brain to analyse this information and, based on training, decide on the actions needed, and

- the physical capability to carry out the necessary task using either fine movements, for instance to adjust a control or forceful ones, as in handling mooring ropes.

The effects of the actions taken need to be monitored to assess the need for future actions. Tasks are often achieved through teamwork and the individual has to co-ordinate their actions with those around them.

The majority of humans, especially those of working age who have selected to work in the same sort of job, have broadly similar capabilities. Factors such as fatigue, mood, experience and age, as well as minor variations in individual capability may also affect performance.

Fig 20.2 Information processing and action – officer of the watch.

C.7.2 Vision

Vision is the main way in which we perceive our surroundings. The eye is capable of responding to a huge range of light levels, but with diminished colour and form perception when light levels are low. It can focus from a few centimetres to infinity, while at short distances (<5 metres) the two eyes, working stereoscopically, provide additional information on distance. Defects in focusing are common and correctable with glasses, contact lenses or by corneal surgery. Other vision defects are rarer, but increase in frequency with age. Age also reduces the ability of the eye to focus and slows the pace of adaptation to changing light levels.

The maritime environment is visually complex, with visibility often reduced by fog, darkness and/or glare and a lack of image contrast is common. Colour is used in navigation lights, on alarms and on charts. Failure to recognise correctly form (visual acuity) and colour can be safety critical. For this reason, some defects may make a person unsuited to safety critical work at sea. These include defects in focusing and in colour perception that cannot be corrected and defects due to light scattering in the eye after corneal surgery and with eye diseases such as cataract.

The eyes of humans are forward facing and so do not detect visual signals beyond their field of view. Other senses, such as hearing, as well as self-awareness of the need to scan widely, lead to the gaze being directed elsewhere. Thus, the control of the eye and head muscles plays an important part in visual performance.

Eyesight standards for seafarers use relatively crude tests of form and colour vision. These are well validated and reproducible but do not effectively assess visual performance under adverse conditions. Tests are available which can do this but they are not sufficiently reliable to be used as the basis for decisions on fitness to work at sea. Information from the light receptors of the eye is transmitted to the visual centres of the brain for analysis through the optic nerve.

C.7.3 Hearing

Voice communications, either direct or relayed by telecoms equipment, are integral to the operation of a vessel. Hearing and comprehension is therefore essential. Sounds can be heard from all directions, and the ears acting together can localise them. This means that sound signals are effective as warnings of danger. If loud enough they can also arouse seafarers from sleep and penetrate through partitions.

Deficient hearing may be congenital, it may be the result of childhood infections or degenerative diseases. It can also be produced by prolonged exposure to loud noise, either at work from noisy machinery or from amplified sounds experienced during leisure. Minor damage to hearing can be detected by audiometry before it becomes apparent or impairing.

Sufficient hearing for communication and for responding to alarms is essential in seafarers. Checking this is a routine part of the seafarer medical. Damage from occupational noise exposure can also be identified using audiometry under controlled conditions. Further information on noise related hearing loss can be found in Ch. 6.6.

In some forms of hearing impairment, hearing aids can enable seafarers to meet the communications demands of their work. If removed when sleeping it is important to ensure that awareness of alarms is still present or to supply an alternative, non-auditory alarm. Not all hearing aids are robust enough for use in a maritime setting, they are liable to damage and all require frequent battery changes.

In noisy settings, ear defenders will reduce the risk of hearing damage. They do not interfere significantly with communication, but models are available with built in speakers to improve communications.

The auditory nerve transmits impulses from the sound sensors in the inner ear to the auditory centres for analysis.

C.7.4 Analysis by the brain (cognition)

Impulses from the eyes and ears, as well as from other receptors all arrive in the brain. Other sensory information comes from

- touch, hot, cold and pain receptors in the skin,

- position sensors in joints and muscle

- taste and smell sensors in the mouth and nose

The information is processed to build up both conscious and unconscious assessments of the surroundings and an important part of this process is the matching of situational information with past experience, including the input from training.

The brain’s state of alertness can vary from high when aroused by important external stimuli to very low, for example, when resting. Alertness is also influenced by other factors such as fatigue, the time of day, food intake, alcohol and some medications. How information is analysed and acted on can be affected by a person’s psychological state, for instance if they are anxious they may over-react to unexpected information, while if they are depressed they may set it aside as unimportant. For this reason effective teamwork and double-checking of decisions is an important method of reducing the risk of inappropriate actions.

If a person is overloaded with information then their performance can decline, particularly where this has significant emotional, economic or safety implications. Prioritisation of inputs and responses to them is an important aspect of brain function, and is one that is particularly sensitive to the effects of fatigue, alcohol and psychoactive substances.

Training and experience make important contributions to the quality of decision taking and can ease the effects of overload by the adoption of tried and tested routines.

Once analysis is complete, either at a conscious or unconscious level, any actions required occur through nerve impulses, mainly to muscle groups that will make the desired action a reality. This may include actions designed to improve the information available for decision taking, such as turning the head and directing gaze in response to a noise.

C.7.5 Physical capability

Work at sea involves a wide range of tasks, many of which are relatively undemanding in terms of muscle strength and stamina, joint flexibility, balance and co- ordination. However some routine duties, such as heavy manual handling, both of mooring ropes and when loading stores or effecting maintenance, demand strength and stamina as well as an adequate response by the circulatory and respiratory systems to increased demands for oxygen and nutrients. Other tasks such as working at heights and entry into confined spaces need good co-ordination and flexibility. Some tasks require the use of breathing apparatus and both physical fitness and mental preparedness are essential for this. In emergencies the physical demands can be much higher, for instance if fighting fires or launching and entering life rafts.

Physical capability is, to an extent, assessed during training, for instance in sea survival and fire-fighting courses. The clinic setting for seafarer medical examinations does not provide opportunities for assessment other than by methods far removed from the realities of work at sea. Most seafarers have a good standard of physical fitness when they are young and starting their career but this may decline through lack of regular exercise or because of illnesses affecting the heart, lungs and bones, muscles and joints.

C.7.6 Impairment, illness and ageing

Seafarers with long service at sea usually retain a good level of physical fitness, provided they do not develop conditions such as heart or lung disease, musculo-skeletal pain or obesity. Some forms of impairment, such as decrements in visual function are very clearly age related, but may be amenable to correction, either by using glasses to compensate for declining acuity or by behavioural adaptations, such as taking more time in the dark before undertaking night lookout duties.

There is an increased incidence of long term illness among older seafarers and an increased risk of medical emergencies arising while at sea. However, the benefits of having seafarers with long experience and high-level skills on board more than compensate for these increments in risk.

Active health promotion programmes for seafarers, both on board and ashore, can be expected to reduce the frequency of career-shortening medical conditions. The requirements in the STCW 2010 amendments that have now come into force and require seafarers to repeat essential safety courses, such as those in fire-fighting and survival at sea can also be expected to provide an incentive for the maintenance of physical fitness. Further information on the training of seafarers is available in Ch. 4.3