MARCUS OLDENBURG, HANS JOACHIM JENSEN, SURESH N IDNANI

The routine activities for Masters, officers and crews are determined by the

- type of ship, for example, container vessel, bulk carrier or chemical tanker, general cargo ship or cruise ship,

- shipping routes,

- particular weather and climatic conditions and

- ship’s operations.

C.4.1 Ship´s routines and watches

HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN, MARCUS OLDENBURG

A 24-hour watch operation on the bridge is required during the sea, river or canal voyage,

but not in the port. Each watch should involve a nautical watch officer and one or more deck ratings. The nautical watch officer takes over the visual and auditory control of the ship's command. This includes navigation and ship safety. As the engines of modern ships can be controlled and operated from the bridge by nautical watch officers, there is no need for corresponding watch keeping by technical officers.

In seafaring today, the three-watch system is most common. The 24-hour day is divided into 6 consecutive periods of watch keeping, and each watch has two periods of four hours on, followed by eight hours off. The 2nd officer is responsible for the so-called 0 to 4 watch (00.00 - 04.00 and 12.00-16.00), the 1st officer for the 4 to 8 watch (04.00-08.00 and 16.00-20.00) and the 3rd officer for the 8 to 12 watch (08:00-12:00 and 20:00-24:00). There is a watch-free operation in the engine room outside of the daily work routine. In the event of machine malfunctions, an alarm is triggered, which leads to appropriate action by the technical officers.

On smaller ships, the two-watch system is often practised by dividing the 24-hour day into 2 watch units. Here the 2nd officer is in charge of the 0 to 6 watch (00:00-06:00 and 12:00-18:00) and the 1st officer for the 6 to 12 watch (06:00-12:00 and 18:00-24:00). In all watch systems, the Master can take over the watch at any time in critical situations.

Other routine tasks in ship operation include maintenance and repair work on deck and in the engine room, cargo handling and cargo securing, acceptance of fuel, spare parts and catering, safety and emergency exercises, administrative work and documentation.

C.4.2 Food

MARCUS OLDENBURG, HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN

The Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (MLC) provides the legal basis for the living conditions on board, including food provisions [1]. It aims ‘to ensure that seafarers have access to good quality food and drinking water provided under regulated hygienic conditions’. A critical appraisal of the MLC reveals that the nutritional situation on board is neither standardised nor mandatory, but adapted to the standard of each member state.

The cook is in charge of the preparation of food on board. In cooking courses lasting only a few weeks, cooks gain basic knowledge on how to manage their job on board. Often they have only a small repertoire of recipes that they repeat every 2 to 3 weeks. The ship’s cook is also responsible for ordering the food and is normally supported and advised by shore based ship-specific caterers. After the provision lists are drawn up, the captain checks and supplements them, according to his own preferences. Furthermore, a low catering budget, the limited possibilities regarding the supply and storage of fresh food during long sea voyages and the often limited access to ports where food can be brought on board pose major problems in the shipboard food provision.

As a rule, seafarers have very little influence on the quality and diversity of their nutrition, especially during sea voyages on board merchant vessels travelling worldwide. Seafarers’ nutrition has often been described as a high-fat diet with a high proportion of meat. Correspondingly, a Nordic study showed that 64% of seafarers were overweight and 23% of them were estimated as being obese [2]. Possible poor nutrition, combined with a lack of exercise and a high level of professional stress, represents a crucial risk factor for cardiovascular disease among seafarers.

In current seafaring situations, warm meals are usually served three times a day. Food is served in the crew’s mess room for the ratings and in the officers’ mess room for the officers. The food available in the mess rooms may differ, taking into account the different cultural requirements and habits. Furthermore, the actual dietary conditions on merchant ships are characterised by a lack of self-determination in the selection of food, different dietary habits in multi-ethnic crews and irregular mealtimes due to the shift pattern on board.

References

1. Maritime Labour Convention (2006). http://www.ilo.org/global/standards/maritime-labour-convention/WCMS_090250/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed at January 2019.

2. Hoyer JL, Hansen H. Overweight among Nordic male seafarers. 8th International Symposium of Maritime Health 2005, Rijeka, Croatia.

C.4.3 Accommodation

HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN , MARCUS OLDENBURG

The accommodation and furnishings on board seagoing ships should contribute significantly to the well-being of seafarers. Due to the short time spent in port, it is now rarely possible for seafarers to ‘get away’ from on board operations by going ashore. Thus, the cabins are the only private retreat for many seafarers. The size, type and furnishing of the accommodation and leisure facilities depend on the type, size and age of the vessels and the rank of the respective seafarer. In general, larger and newer vessels usually offer better accommodation and amenities than older and, particularly, smaller ones. In many cases, the former have far better leisure facilities with a fitness room and a swimming pool. In contrast, accommodation on small ships, such as the ships in the feeder services of North Sea and Baltic Sea traffic, is cramped and often there is no space for a fitness room. In addition, the crews on smaller vessels often do not have internet access in their cabins. Seafarers are often affected by vibration and noise whilst in their cabins and the normally sparse furniture in the seafarers’ accommodations may be firmly anchored to the floor to prevent movement during high seas.

The accommodation and furnishings on board seagoing ships should contribute significantly to the well-being of seafarers. Due to the short time spent in port, it is now rarely possible for seafarers to ‘get away’ from on board operations by going ashore. Thus, the cabins are the only private retreat for many seafarers. The size, type and furnishing of the accommodation and leisure facilities depend on the type, size and age of the vessels and the rank of the respective seafarer. In general, larger and newer vessels usually offer better accommodation and amenities than older and, particularly, smaller ones. In many cases, the former have far better leisure facilities with a fitness room and a swimming pool. In contrast, accommodation on small ships, such as the ships in the feeder services of North Sea and Baltic Sea traffic, is cramped and often there is no space for a fitness room. In addition, the crews on smaller vessels often do not have internet access in their cabins. Seafarers are often affected by vibration and noise whilst in their cabins and the normally sparse furniture in the seafarers’ accommodations may be firmly anchored to the floor to prevent movement during high seas.

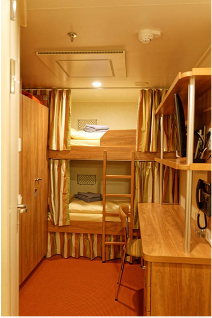

Even on the large cruise ships with a high number of seafarers, accommodation is cramped, especially for the ratings. They may have 6 to 10 m2 twin cabin with bunk beds and a small separate bathroom. A curtain in front of each bed provides the only individual privacy. Often they are inside cabins, or cabins below the water level, without portholes. The officers' single cabins are normally bigger, with portholes or a window, and the captain and other senior officers, may have a suite with several rooms.

The MLC contains requirements for newer ships in terms of the size of accommodation, heating and ventilation, sanitary facilities, noise and vibration as well as lighting and hospital facilities. According to the Lloyd's Register Educational Trust[1], there are significant differences in the quality of accommodation and facilities on board, and a high percentage of seafarers are dissatisfied with their accommodation.

C.4.4 Leisure time on board

HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN, MARCUS OLDENBURG

With decreased time spent in port and therefore restricted access to shore based facilities, long periods of separation from their social environment, high job demands and no strict separation of work and leisure time at sea, sufficient recreation facilities on board are important for the wellbeing of the seafarers.

Leisure activities available on board depend on the type of ship, the equipment in leisure rooms, the sailing area and the composition and size of the crew. Cultural behaviour patterns as well as the work situation on board also have an influence on leisure behaviour. A distinction can be made between individual and collective as well as active and passive leisure activities. On board, the focus is more on passive behaviour, for instance watching DVDs, listening to music or just relaxing. Sports activities are more frequent on ships operating worldwide than on small feeder ships and seafarers on these worldwide vessels generally have fewer opportunities for leisure time spent off the ship. There are also differences between the different occupational groups. Amongst the ratings, with their typically higher level of physical job tasks, there is little willingness to do sport. Sitting together and karaoke are common leisure activities among Eastern Asian seafarers, especially Filipinos. Officers, on the other hand, are more likely to find an individual sporting activity.

In feeder shipping with its special workload caused by irregular and often long working hours, seafarers prefer using their leisure time for recreation and sleep. Due to the better communication possibilities in the coastal area, contact with their families is paramount to the crews. The psychosocial leisure environment, which includes the possibility of IT contacts with their families, is particularly important for East Asian seafarers with their rather socio-centric values.

In contrast, newer cruise ships with a high number of seafarers have more extensive recreational facilities. They may include a separate sport and fitness room, bar, other recreation rooms, swimming pool and a separate deck area for the crew’s leisure activities, for example for sunbathing. The use of such facilities varies depending on the occupational group and culture-specific differences. Parties are organised for various occasions such as birthdays, crew change etc., often with alcohol offered. These leisure time events also serve as an important source of relaxation after a hard working day.

C.4.5 Physical fitness opportunities

MARCUS OLDENBURG, HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN

The opportunity for physical training is important, especially during long, tedious voyages. Here, seafarers often perform monotonous job-related activities in which some of their muscles are not used sufficiently. In addition to the health benefits, sport also encourages team building due to social interaction. Since recreation time is often limited in seafaring, especially on board feeder ships, time for physical activity has to fit in with the daily work schedules on board. For successful implementation of fitness on board, a positive attitude towards fitness training is necessary on the part of the shipping company. Although several shipping companies have already improved shipboard exercise opportunities in recent years, there are still a lot of vessels without sufficient or suitable facilities. A well-equipped fitness room should contain cardio-training equipment such as treadmills, steppers, rowing machines or bicycles. Weight benches or balls are also often used in fitness rooms. Music, positive pictures, sufficient lighting and a view outside the exercise room may raise the motivation for fitness activities.

Motivating seafarers to do enough physical activity can be demanding. A prerequisite for such motivation is that the seafarers enjoy the physical activities on board. It is particularly important that the Master and other officers should take part in the fitness programme to set an example. Organised sports events or competitions on the ships, in which the seafarers can pit their strength against each other, either individually or in groups, provide a strong motivation for exercise.

C.4.6 Social life

HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN, MARCUS OLDENBURG

Practically speaking, the most important characteristic of a seafarer’s life on ships is the lack of demarcation between work and leisure time. The seafarers work and live together over several months in a heterogeneous group from different cultures. Consequently, the majority of the crew do not normally talk in their native language − neither during their working time nor in their leisure time − which may lead to comprehension problems and affect their well-being. The hierarchical crew structure among the different occupational groups also influences social life on board. The different lengths of the seafarer’s time on board as a rule, 4 months for European officers and up to 12 months for East Asian crew ranks, lead to frequent changes in the personnel on board. New seafarers signing on can change the communication and social relationships on board considerably. In addition to these basic conditions of ship operation, different cultural standards and cultural backgrounds in a multi-ethnic crew also influence the social life on board. The sociocentric orientation of the East Asian seafarers, with the Philippines as the largest group in terms of numbers, leads to a pronounced attachment to their own ethnic group. Often, however, they complain about poor communication on board and feel discriminated against. Consequently, this occupational group often express a feeling of loneliness. The situation is different among the seafarers of European cultural context, who are mostly officers. However, ties to their own communicative cultural background can also increase the social distance on board, especially towards subordinate seafarers.

The large and very heterogeneous crews on cruise ships often come from more than 40 different nations, and this determines social life on board. The crew structure, especially in the hotel sector, comprises very different occupational groups, from service personnel to that in the wellness and entertainment areas. The close coexistence of people from different nations also leads to stronger social control. The need for cohesion in one's own linguistic-cultural group offers a certain protection in this context. Nevertheless, withdrawal and isolation of seafarers also frequently occurs on cruise ships.

C.4.7 Time off in port

HANS-JOACHIM JENSEN, MARCUS OLDENBURG

During their time on board, the seafarers integrate into the closed social system of the ship with its hierarchical structure. Face-to-face communication over a long time may be limited to a few colleagues, leading to rather narrow communication on board with hardly any new content. This is why contact opportunities and new communication partners outside of the on board operation are very important for maintaining social competence. They allow the seafarers to leave their roles in the hierarchical ship operation and use different contact and communication means, at least for a short time.

The main reasons for going ashore are communication with the family, transferring money to the family and using shopping facilities for essential items. The desire to visit a bar or for other amusements is rather rare in many seafarers. To do so would mean spending money, which is something many seafarers, particularly non-Europeans, want to avoid.

The growing efficiency in maritime port turnover has led to a significant reduction in the time that seagoing vessels spend in port. In combination with strict security requirements in many ports in accordance with the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code, this has significantly reduced the shore leave opportunities for seafarers. Public health concerns such as the 2020/21 pandemic can also lead to further restrictions. In addition, the ports may be relatively far away from the central urban area and there are often insufficient or no transfer possibilities. Feeder vessels have a particularly short time in port. During these short berthing periods, these ships often have to call at several terminals for the unloading and loading of cargo. This requires the seafarer’s presence on board for the ship's manoeuvres. In addition, maintenance and repair work that cannot be carried out during the voyage is often necessary, especially in the engine room. The officers are even more closely involved in on board operations including port clearance, monitoring of cargo handling and bunkering. Due to the mentioned problems, many seafarers prefer visiting welfare organisations in the proximity of the port.

C.4.8 Women Seafarers

SURESH N IDNANI, HANS JOACHIM JENSEN, MARCUS OLDENBURG

A career in the maritime industry is not considered mainstream or ‘professional’, and is also not very well known to many young women. Nevertheless, the maritime industry is now seeing women seafarers enrol in a once male dominated shipping career.

In 1988, few maritime training institutes accepted female students. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) was instrumental in establishing global programme known as the Integration of Women in the Maritime Sector (IWMS). The primary objective was to encourage IMO member States to open the doors of their maritime institutes to enable women to train alongside men and so acquire the high-level of competence that the maritime industry demands. The programme includes but is not limited to

- strengthening national and regional capacities through gender-specific fellowships

- facilitating access to high-level technical training for women in the maritime sector in developing countries and

- facilitating the identification and selection of women by their respective authorities for career development opportunities in maritime administrations, ports and maritime training institutes.

IMO's programme is now 30 years old and continues to empower women to fuel thriving economies, spur productivity and growth, and benefit every stakeholder in the global maritime community.

Women seafarers may also have to deal with discrimination, bullying and harassment, including sexual harassment or even abuse while at sea. Many maritime unions and companies are alert to these dangers and strive to protect the interests of women members – who now number about 23,000 worldwide (10).They are also are more susceptible to social isolation than their male counterparts and it is worth considering employing more than one female seafarer on the same voyage when possible. Guidelines in this area have been produced by the ITF (16).

A 2014 study looked at the health and welfare needs of women seafarers and how organisations can best make or campaign for improvements to the health information and services available to women seafarers (17). The responses received highlighted a small number of areas where relatively simple and low-cost interventions might improve the health and welfare of women seafarers. Specifically, these include:

- the production and appropriate distribution of gender-specific information on back pain, mental health and nutrition in addition to gynaecological complaints,

- the introduction of means for disposing of sanitary waste for all female crew on all ships and

- the improved availability of female specific products e.g. sanitary products in port shops and welfare centres worldwide.

In addition, much work needs to be done to build confidence amongst women seafarers in being able to speak confidentially with the officer responsible for medical care and in addressing sexual harassment. The support of all of the main stakeholders is important to carry on with further work in this area.

[1] Ellis, N., Sampson, H., Acejo, I., Tang, L., Turgo, N., Zhao, Z Seafarer. Accommodation on Contemporary Cargo Ships. The Lloyd's Register Educational Trust Unit, December 2012

[2] Oldenburg M, Jensen HJ. Recreational possibilities for seafarers during shipboard leisure time. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019 Oct;92(7):1033-1039. doi: 10.1007/s00420-019-01442-3. Epub 2019 May 21. PMID: 31114964