VIVEK MENON

C.3.1 Organisational structure on board

The crew of a ship are the personnel who sail on board and are responsible for its operation, primarily when the ship is at sea. They also have some responsibilities when in port. All ships, i.e. cargo and passenger ships have similar crew departments. However, in addition, passenger ships carry passenger service and entertainment staff, who, for the purpose of this chapter are referred to as non-traditional crew. The traditional crew of a ship are divided into three departments:

- Deck department

- Engine department

- Catering (steward’s) department

The bridge of a ship is the navigation hub fitted with advanced machinery systems for safe navigation. Seafarers in the deck department, mainly deck officers and ratings, are responsible for the navigation of the ship, handling of cargo operations and machinery on the deck of the ship.

The engine department includes marine engineer officers and ratings responsible for operation and maintenance of the ship’s machinery. The engine room houses the propulsion and power generating machinery required for the safe operation of the ship.

The catering department is responsible for the preparation of meals and general housekeeping for crew and passengers. The number of personnel in this department varies with the type of ship. Passenger vessels would have several members and ranks while a cargo ship may have only a couple of members owing to the difference in the number of people on board.

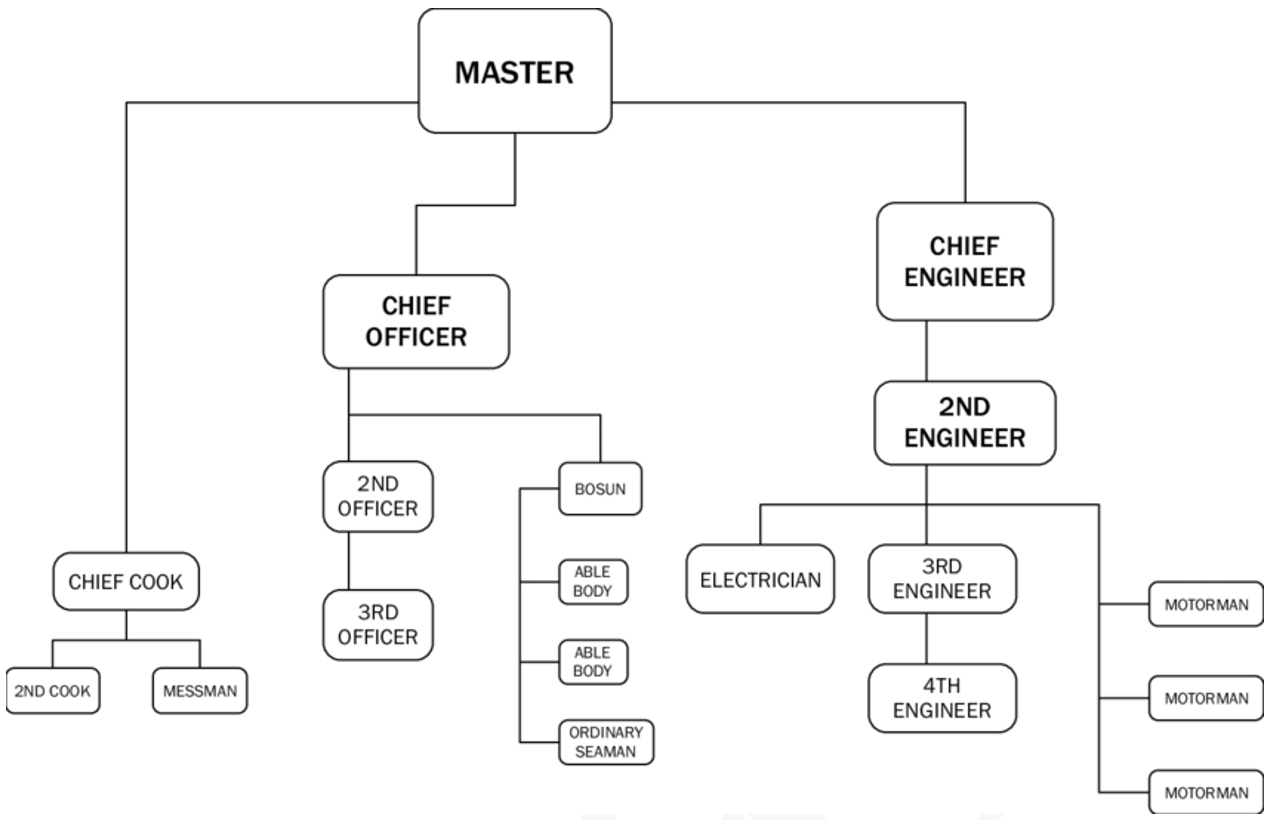

Figure 1: Typical ship-board organisational chart – Credit T. Bielić, D. Ivanišević, A. Gundić: Participation-Based Model of Ship Crew Management

Figure 1: Typical ship-board organisational chart

The Master is the ship's highest responsible officer, acting on behalf of the ship's owner / operator or manager. He may be one of a number of seafarer’s on board to hold a Master Mariner certificate and hold the rank of Captain but only one person can be the Master of the ship. The Master is legally responsible for the day-to-day management of the ship. It is his responsibility to ensure that all the departments perform legally to the requirements of the ship's owner /operator or manager. The ship has a number of deck officers that assist the Master. In addition, the Master also has the advice of pilots when the ship is navigating in restricted waters, such as narrow or shallow channels. Each shipboard department has a designated head who reports to the Master.

The deck department is headed by the Chief Officer. The engine department is headed by the Chief Engineer. The Chief Steward is the head of the catering department.

C.3.2 Deck Department

Chief Officer

The Chief Officer, also called the First Mate, is the head of the deck department. He is second-in-command after the Master. The Chief Officer's primary responsibilities are the vessel's cargo operations, its stability, and supervising the deck crew. The Chief Officer is responsible for the safety and security of the ship, as well as the welfare of the crew on board and usually is the officer responsible for medical care on board. The Chief Officer typically stands a bridge watch from 0400 to 0800 hours and from 1600 to 2000 hours, the 4 - 8. Additional duties include ensuring good maintenance of the ship's hull, cargo gears, accommodation and the lifesaving and firefighting appliances. The Chief Officer also trains the crew and cadets on various aspects like safety, firefighting, search and rescue and various other contingencies. The Chief Officer may or may not have a Masters certificate that would allow him to take over duties from the Master should that be necessary.

Second Officer

The Second Officer, also called Second Mate, is usually in charge of ship navigation with a position below Chief Officer and above the Third Officer. He is the third in command, after the Master and Chief Officer. The second officer typically stands the bridge watch from 1200 to 1600 hrs and again from 0000 to 0400hrs, the 12 - 4. In some companies, the Second Officer is the officer responsible for medical care on board.

Third Officer

The Third Officer (also called the Third Mate) is primarily charged with the safety of the ship and crew and ensuring good maintenance of the lifesaving and firefighting appliances and generally serves as the ship's chief safety officer. The Third Officer is the next licensed position on board the vessel, as fourth-in-command and usually stands the bridge watch from 0800 – 1200 and 2000 – 2400, the 8 - 12.

Deck Cadet

The deck cadet is the trainee officer on board, fresh out of maritime school with the least experience on board ships. His task is to learn, comprehend and apply skills for the process of becoming a skilled officer in the future.

Boatswain:

The boatswain, who may also be known as the Bosun or ‘Chief Petty Officer’ (CPO), is the highest ranking unlicensed rating in the deck department. The boatswain generally carries out the tasks instructed by the Chief Officer, directing the able seaman and ordinary seaman. The boatswain generally does not stand a navigational watch.

Pump Man

The Pump Man works on tankers carrying liquid, gas or chemical cargo, ensuring the safe operation of pumps and the discharge of liquid cargo - mostly petroleum products. He plays a major part during loading and discharging, mainly opening valves as per the Chief Officer’s instruction, taking ullage and sounding measurements, etc. The Pump Man is also responsible for maintaining and repairing all cargo handling equipment on the vessel. This rank is equal to Bosun and mostly works independently, taking orders directly from the Chief Officer.

Able Seaman

An Able Seaman (AB) works under the Boatswain, completing tasks such as working mooring lines, operating deck gear, standing anchor details, and working cargo. An AB also stands a navigational watch, generally as a lookout or helmsman, also known as quartermaster.

Ordinary Seaman

The lowest ranking personnel in the deck department. An Ordinary Seaman (OS) generally helps out with work that the Able Seamen do. Other tasks include standing lookout, and general cleaning duties.

C.3.3 Engine department

The engineers on board ships are also called technical officers. They are responsible for maintaining the machinery and ensuring it is operational. Today, ships are complex systems that combine a lot of technology within a small space. This includes not only the engines and the propulsion system, but also for example, the electrical power supply, devices for loading and discharging, garbage incineration and freshwater generators. Additionally, more and more environmental protection technologies, fuel treatment systems and cargo conditioning devices are used on board ships. The upkeep of all these are in the hands of engine department staff.

Chief Engineer

The Chief Engineer on a commercial vessel is the official title of someone qualified to manage and oversee the engine department. The Chief Engineer is responsible for the operation and maintenance of all of the engineering equipment throughout the ship and must be in possession of the appropriate Chief Engineer license as per STCW requirements. According to the Safety of life at sea (SOLAS) convention, it is the responsibility of the chief engineer to look after the safety of maritime professionals working in the engine room. The duties of the chief engineer are clearly mentioned in STCW 95 section A- III /2 (as amended). The Chief Engineer has other licensed engineers to assist with engine room watch and the performance of maintenance and repair of machinery on board ship.

Second Engineer

The Second Engineer, also called First Assistant Engineer, is the officer responsible for supervising the daily maintenance and operation of the engineering systems. He/she reports directly to the Chief Engineer. The Second Engineer is second in command in the engine department after the Chief Engineer. The duties of the chief engineer are clearly mentioned in STCW 95 section A- III /2 (as amended)

Duties include but not limited to the following:

- ensuring safety of personnel, their rest/working-hours;

- upkeep of safety equipment and pollution prevention equipment;

- operation and maintenance of equipment’s in the engine rooms and deck machinery;

- engine room management – for e.g. duties of other engineer and management of spares;

- documentation and record keeping in accordance to international, national and company rules and regulations;

- Training of junior and fellow colleagues.

The person holding this position is typically the busiest engineer on-board the ship, due to the supervisory role this engineer plays and the operational duties performed. Operational duties include responsibility for the main engines, refrigeration systems and any other equipment not assigned to the third or fourth engineers. The second engineer may or may not hold a Chief’s ticket that would allow him to assume the role of Chief Engineer if necessary.

Third Engineer

The Third Engineer is junior to the Second Engineer in the engine department and is usually in charge of boilers, fuel, auxiliary engines, condensate, and feed systems. Duties include but not limited to, performing independent engine watch, bunkering, if the officer holds a valid certificate for fuel transfer operations) and execute maintenance and repairs on equipment as delegated by the second engineer. On some ships the bunkering task responsibility may be shared between the Chief Officer and Second Engineer.

Fourth Engineer

The Fourth Engineer is junior to the Third Engineer in the engine department. As a junior marine engineer of the ship, he is usually responsible for the maintenance of electrical systems, sewage treatment, lube oil, bilge, and oily water separation systems. Depending on the vessel and manning, this person usually stands a watch. Moreover, the Fourth Engineer may assist the Third Officer in maintaining proper operation of the lifeboats.

Trainee Marine Engineer

Trainee Marine Engineer, also known as Engine cadet, usually accompanies the Second Engineer, to assist and learn while observing and carrying out activities in the engine room.

Electro-Technical Officer

The ElectroTechnical Officer (ETO) handles various aspects on board a ship related to the electrical systems. The ETO usually reports to the Chief Engineer and organises his jobs in consultation with the Second Engineer. He handles the maintenance of various electrical systems in the engine room and the navigational equipment on the bridge. The myriad systems he would be working on would be as varied as the refrigeration system to the emergency systems or fire alarms and detectors to navigational lights and battery backups to electrically operated propelling machinery. Due to a general decrease in manning levels many vessels do not carry an ETO and hence these duties must be performed by other seafarers in addition to those duties already described.

Fitter

Fitters are certified professionals in welding and are skilled operators of the lathe machine. Their role is to ensure the proper fitting of the engine and other electrical parts in the engine room as well as to repair or fabricate pieces required for repairing broken/cracked components. They are important because of their technical and fitting skills, as well as their knowledge that is more technical rather than theory based.

Motorman

Motormen hold a watch keeping certificate and can stand watch along with Engineer Officers. They are delegated jobs by the Second Engineer and usually assist the Engineer Officers in the maintenance of machinery and keeping a track of operating parameters of the machinery.

Oiler

The Oiler does maintenance work in the engine room and does not hold a watch keeping certificate. He assists the duty Engineer at watch, if the ship is not an UMS ship. They assist Engineers in overhauling machinery, cleaning and painting etc. This rank is equal to an AB in the Deck Department. At times the oiler with experience may become a Pump Man.

Wiper

Wipers are responsible for assisting with the cleaning and maintenance of the engine room. They are usually not certified watch keepers although they may progress from this rank to that of a Motorman or Oiler after obtaining a watch keeping certificate and completing the required sailing time.

C.3.4 Steward's department

Chief Steward

A Chief Steward is the senior crew working in the galley department of a ship. Since there is no purser on most ships, the steward is the most senior person in the department, hence the name. The Chief Steward directs, instructs, and assigns personnel performing such functions as preparing and serving meals, cleaning and maintaining officers' quarters and communal areas, and receiving, issuing, and keeping an inventory of the stores. The Chief Steward also plans menus and compiles supply lists, overtime, and cost control records.

A Chief Steward's duties may overlap with those of the Steward's Assistant, the Chief Cook, and other steward's department crew. On large passenger vessels, the Chief Steward is known as the Passenger Services Director or Purser and is a high ranking officer. Here they are responsible for many staff including galley staff, restaurant and bar staff, reception staff, tours staff, housekeeping staff and staff tasked with the administration of potentially many thousands of crew members.

Chief Cook

A Chief Cook, also known as Cook, is the most senior seafarer in the Chief Steward's department of a merchant ship. On some ships, the Chief Cook is the senior most person in this department. The Chief Cook directs and participates in the preparation and serving of meals, determines the timing and sequence of operations required to meet serving times, inspects the galley and equipment for cleanliness and oversees the proper storage and preparation of food. The Cook may plan or assist in planning meals and taking an inventory of stores and equipment.

A Chief Cook's duties may overlap with those of the Steward's Assistant, the Chief Steward, and other steward's department crewmembers.

It is important to note that not all the roles described above may be presented onboard every vessel. This will depend on the size and operational complexity of the vessel.

C.3.5 Numbers of crew

The IMO has laid down the Principles of Safe Manning, the objectives of which are to ensure that a ship is sufficiently, effectively and efficiently manned to provide safety and security of the ship, safe navigation and operations at sea, safe operations in port, prevention of human injury or loss of life, the avoidance of damage to the marine environment and to property, and to ensure the welfare and health of seafarers through the avoidance of fatigue.

Most vessels require a crew of 20-25 personnel consisting of officers (Master, Chief Engineer), specialist technicians (Electrical or Gas Engineers) and crew or ratings (Able seaman). Crew size and its onboard organisation structure depends on the size and operational complexity of the vessel. For e.g. a very large tanker vessel carries out more complex operations and they may require a larger crew.

Below table provides a very generic overview of the number of crew that may be on different types of vessels:

Vessel Type | Average Crew size |

General cargo | 20-25 |

Oil Tanker | 20-26 |

LP/LNG | 15-24 |

Bulk carrier | 20-24 |

Container | 15-25 |

Passenger | 100-2000 |

Large Fishing vessel | 30-50 |

C.3.6 Non-Traditional crew

Passenger ships in addition have passenger service and entertainment staff to take care of passengers on board. For example, a large Cruise Ship may carry around 2000 non-traditional crew members. Some of the ranks of non-traditional crew are listed below -

- Waiters and wine waiters

- Bar Staff

- Chefs and Galley Staff

- Back of House Staff

- Cabin Stewards

- Entertainment staff

- Tour staff

- Youth staff

- Shop Staff

- Beauticians and Hairdressers

- Casino Staff

- Medical staff

Additional information on passenger shipping is available in Chapter 2.12.

C.3.7 Interaction between ship and shore staff

In the early days of shipping, when vessels were at sea seafarers were totally cut off from shore‐side personnel. Even in port, vessels were normally out of contact with ship and cargo owners. Hence, the Master was in charge of all matters relating to trade, human resources, and finance. By contrast, in the modern context, ships are much more connected whilst at sea, by email, telephone and fax. Once in port, they are visited by a huge range of port and harbour officials. These interactions with office personnel and officials are vital to the smooth, and safe, operation of vessels. However, they are far from straightforward given that they take place in environments where communication may be challenging as a consequence of language, culture, time pressures, noise levels, stress and bureaucracy.

Personnel with whom seafarers interact can be broadly divided into those who are encountered in ports, usually face to face, and those who run shore‐side operations pertaining to the vessels. Although there are some exceptions, most seafarers do not have sustained relationships with the personnel they directly encounter in ports. Seafarers are more likely to enjoy longer‐term relationships with ‘operations’ personnel associated with their company, although this may often be in the absence of any direct face to face contact.

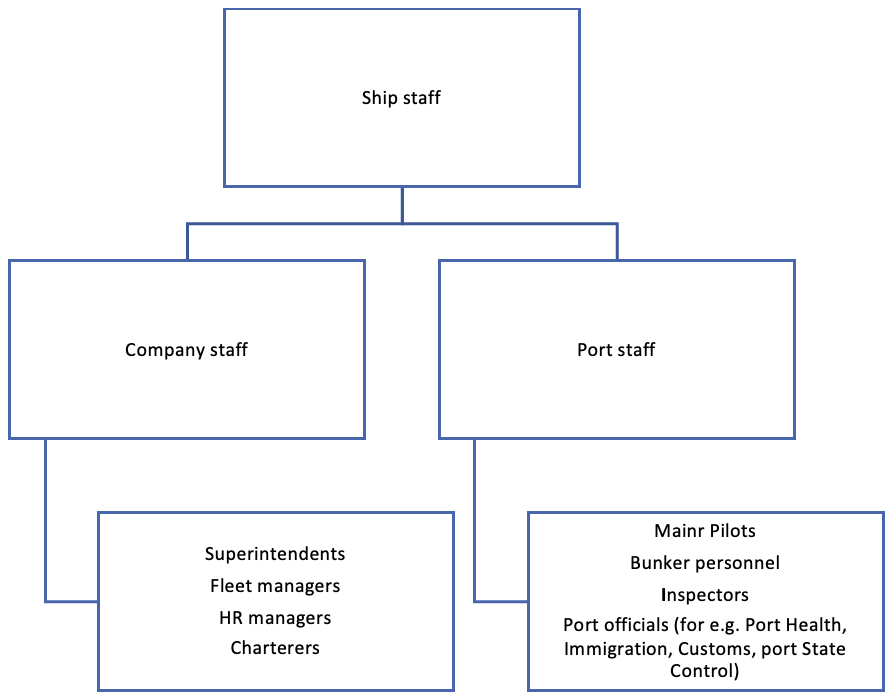

Figure 2 provides an overview of the personnel with whom seafarers interact.

Figure 3: Overview of ship-shore interactions

Ship‐staff and port‐personnel

Marine Pilots:

A marine pilot, also called maritime pilot, harbor pilot, port pilot, ship pilot, or simply pilot, is a mariner who maneuvers ships through dangerous or congested waters, such as harbors or rivers. They are navigational experts possessing knowledge of the particular waterway, licensed or authorised by a recognised pilotage authority. The pilot becomes an integral part of the Bridge Team Resource when navigating through dangerous and congested waters. The relationship between a Pilot and Master is an intriguing balance of mutual trust and respect, which is largely unwritten. During pilotage, the Masters is still in command of their vessel, however, the Pilot advises on direction of the movement of the vessel in order to transit the local channels, waterways etc.

Bunker personnel:

Bunkering is the supplying of fuel for use by ships. Bunkering may take place offshore, at anchor or alongside. It may be pumped from road tanker, bunker barge or another tanker or ship, and the people who work in providing this service are referred to as bunker personnel. Whatever the provider, the procedures followed are similar. Bunkering should be considered a high-risk operation, where mistakes can result in pollution, high financial penalties or even imprisonment. The Master is responsible for the overall operation, whilst the Chief Engineer is responsible for matters that concern the engine room including fuel oil systems, bunkering operation and quality of oil received.

Inspectors:

There are different types of inspectors who come onboard vessels and interact with the Master and crew. For e.g. Flag State Inspectors are used by flag states to ensure satisfactory standards are being maintained on board vessels flying their flag. Flag State Inspectors conduct a verification of statutory documentation and a general examination of the vessel's structure, machinery and equipment as well as a more thorough inspection and/or operational testing of firefighting equipment, lifesaving appliances and safety equipment.

Marine surveyors

A Marine surveyor (including "Yacht & Small Craft Surveyor", "Hull & Machinery Surveyor" and/or "Cargo Surveyor") is a person who conducts inspections, surveys or examinations of marine vessels to assess, monitor and report on their condition and the products on them, as well as inspects damage caused to both vessels and cargo.

Port Officials:

Just like when a person arrives in an airport they undergo immigration, customs and health clearance procedures, vessels and its crew experience the same which commonly known as vessel clearance procedures. Vessel clearance procedures are carried out by government port officials such as Port Health, Immigration and Customs. They verify documents presented by the Master for any non-compliance in accordance to the local law. Port State control (PSC) inspections of foreign ships are conducted by port State control officers (PSCOs) in national ports to verify that the condition of the ship and its equipment comply with the requirements of international applicable mandatory regulations and that the ship is manned and operated in compliance with these rules.

Vulnerability of seafarers and ships

Ships and seafarers in port are vulnerable to local officials who might cause delays and have the power to fine, detain, and tarnish the reputation of a vessel and to place criminal charges and even enforce the imprisonment of seafarers. In many areas of the world, the vulnerability of vessels and seafarers is not generally exploited by port‐based personnel. However, in some places such exploitation is routine and takes the form of demanding ‘gifts’ of produce and cash. There have also been cases, where port personnel were found to steal from seafarers and from ships and to abuse their power in order to extort cash from individuals.

C.3.8 Ship staff and shore‐based vessel personnel

Superintendents:

A Superintendent is a person ashore, responsible for providing organisational and operational support to the ship, and to facilitate safe and efficient running of the ship.

A superintendent using their knowledge and understanding of human resource management which is vital part of ship operations shall be able to provide support and supervision to the ships management, for operating and maintaining the ship to the relevant international, national, classification society and company requirements. A superintendent also supervises and directs shipyards, technicians and others for maintaining the ship to the required standards. A superintendent with the help of the Master and Chief Engineer evaluates the condition of the ship, by carrying out periodic inspections and by obtaining necessary reports from the ships and others. Additionally, a superintendent manages the ship operating costs and control costs based on the business goals of the organisation, while maintaining the ship in compliance with all mandatory regulations and local regulations.

There are primarily 2 categories of ships' superintendents (Marine and Technical) in accordance to their applicable competence and support to ships.

Marine superintendent: The person ashore, responsible for providing nautical and operational support to the ship, and to facilitate safe and efficient running of the ship.

Technical superintendent: The person ashore, responsible for providing technical and operational support to the ship, and to facilitate safe and efficient running of the ship.

Fleet managers:

A Fleet Manager is a key position within any shipping company and this role is usually responsible for all operational aspects and budgetary control of the company’s vessels. Depending upon the company, this position together with superintends could involve the management of as few as 2 or 3 vessels up to perhaps as many as 30+ vessels.

HR managers:

HR Manager (also known as Marine HR manager) in close liaison with officers and crew onboard ships plays a key role in the safe performance of a shipping company. The role and responsibilities vary from managing recruitment, crew planning, training and development, cost monitoring and general HR matters, ensuring positive co-operation between the vessels and the office in delivering a safe and efficient operation to the satisfaction of all the company. Additionally, the HR manager ensures compliance to regulatory and industry standards as well as company standards by overseeing various elements within departments. This role is a crucial link between seafarers onboard, Marine HR, technical as well as commercial departments.

Charterers:

Chartering is an activity within the shipping industry whereby a shipowner hires out the use of their vessel to a charterer. A charterer may own cargo and employ a shipbroker to find a ship to deliver the cargo for a certain price. Some charterers own ships themselves, either on a leased or permanent basis, chartering vessels from independent ship owners when the need arises. The charterer maintains a close relationship (or communication) with the Master of the hired vessel and the shipping company to ensure that reasonable and careful inspection and maintenance of the vessel is performed in accordance with the custom of the trade. This practice ensures that the shipowner is exercising due diligence to make the vessel seaworthy to carry the charterer’s cargo. Sometimes, an inspection from the charterer is warranted for this purpose.

Cooperation between ship- and shore-based personnel

Sea‐staff, depending on the nature of trade have limited opportunities for face to face interaction with employees working in the shore-based offices of their companies. Superintendents are the most usual point of contact between companies and their sea‐staff and therefore play an important role. Much interaction between sea‐staff and office-based personnel, including charterers, takes place by email and telephone. Historically, superintendents generally adopted a managerial and hierarchical approach when visiting ships. Hence sea staff felt that they were on ‘the other side’ of what emerged as a considerable gulf between ship and shore staff working for the same companies. Poor relationships between company personnel and ship personnel resulted in the majority of seafarers feeling unable to report the full truth about a situation on board to company personnel ashore.

However, we do see some examples with certain companies who are trying new ways to better their ship-shore communications, provide improved conditions and communications structures of interaction between their sea-shore based staff. For e.g. with better technology available onboard, practice of regular phone calls take place and in some cases video calls are getting more common. Some companies provide regular group calls with their fleet of vessels to share pains and gains during their vessel operations. Depending on the company the hierarchical approach towards Master and crew onboard have changed to being more of proving decision support as and when needed by the vessel. Some companies include better training of shore based personnel to support seafarers and pursue practices which are likely to improve the mutual understandings of seafarers and shore staff in relation to their respective jobs and working environments (for e.g. shipboard placements for management staff without sea‐experience, rotations of seafarers between shore and shipboard jobs, company seminars and training events etc).

C.3.9 Job demands for different positions

Physical and mental requirements

Seafarer’s job demands on board various types of ships include routine and emergency duties.

Often, this is also in the context of the seafarer living on board as well - in many cases the ship is both home and workplace. Seafarers need to be able to adjust to living and working conditions on board ships, including

- the requirement to keep watches at varying times of the day and night,

- the motion of the vessel in bad weather,

- the need to live and work within the limited spaces of a ship,

- the physical demands of climbing ladders etc and lifting heavy objects

- working under a wide variety of weather conditions.

One way of classifying seafarer’s job demands is by their functions and levels of responsibility. Typically, there are seven functional areas, at three different levels of responsibility. The levels of responsibility are:

- management level, applies to senior officers

- operational level, applies to junior officers

- support level, applies to ratings forming part of a navigational or engine watch

The following table lists the different functions and levels of responsibility at which the functions can be carried out.

Function | Level of responsibility | |||

Management | Operational | Support | ||

Deck | Navigation | x | x | x |

Cargo handling and stowage | x | |||

Deck & Engine | Controlling the operation of a ship and care for persons on board | x | x | |

Engine | Marine engineering | x | x | x |

Maintenance and repair | x | x | ||

Electrical, electronics and control engineering | x | x | ||

Radio | Radio communication | x | ||

These functions can be further broken into what is practically required of the seafarer. It then becomes possible to identify some of the physical and mental demands placed on the seafarer in order for them to carry out both their routine and emergency duties.

General tasks on board | Physical/mental demands |

Routine movement around vessel: – on moving deck – between levels – between compartments | • be able to maintain balance and move with agility • be able to climb up and down vertical ladders and stairways • be able to step over coamings around cargo hatches of certain heights • be able to open and close heavy watertight doors |

Routine tasks on board: – use of hand tools – movement of ship’s stores – overhead work – valve operation – standing a four-hour watch – working in confined spaces – responding to alarms, warnings and instructions – verbal communication | • be able to use physical strength, dexterity and stamina to use mechanical devices • be able to lift, pull and carry a load • be able to reach upwards • be able to stand, walk and remain alert for an extended period • be able to work in constricted spaces and move through restricted openings (e.g. openings in cargo spaces and emergency escapes) • be able to visually distinguish objects, shapes and signals • be able to hear warnings and instructions • be able to give a clear spoken description |

Emergency duties on board: – escape – firefighting – evacuation | • be able to use lifesaving and safety appliances (e.g. lifejacket, immersion suit, safety harness, breathing apparatus, etc.) • be able to escape from smoke-filled spaces • be able to take part in fire-fighting duties, including use of breathing apparatus • be able to take part in vessel evacuation procedures |

Living and social conditions: – isolation – – evacuation | be able to live and work with same people for long periods of time be able to occasionally live and work under stressful conditions be able to deal with isolation from family and friends be able to work with and interact person of various cultural background |

Some of these demands will be more relevant than others, depending upon the seafarer’s duties. For example, the chief steward or cook is unlikely to be part of the firefighting team. However, the ship is an enclosed community, and many tasks may need to be done by many different people, particularly if a seafarer becomes ill or is injured.

Emergency duties

In the case of an emergency or other situation where the safety of the ship, of any person on board, or of the marine environment is at stake, the Master, officers and crew are required to assist and offer their help without being requested to do so. Traditional and non-traditional crew on board ships have specific duties during emergencies and the main ship incidents are described in Chapter 2.1.3.

Depending on vessel type, audio-visual alarms inform the crew of the type of emergency and the crew must then muster and carry out their emergency duties. Different teams are compiled to tackle emergencies, and these are described in Chapter 4.3.9.

Tasks performed as part of the emergency duties of traditional crew include:

- Wearing a fire suit with breathing apparatus

- Recovering casualties or injured persons from confined spaces

- Carrying breathing apparatus bottles

- Closing fire dampers

- Acting as back up

- Carrying out technical tasks

- Rigging and operating fire hoses (usually heavy)

- Preparation, launching, manoeuvring and recovering of the lifeboat or rescue boat.

Whilst non-traditional crew, for example passenger service and entertainment staff, may need to perform the following tasks:

- Forming part of a lifeboat crew

- Assisting the firefighting team with boundary cooling using heavy hoses

- Assisting as stretcher party of possible casualties or injured persons

- Assisting as messengers having to go up and down up to eighteen decks on foot

- Assisting by being a part of the lifeboats crew

- Helping to push the lifeboat away from the ships side, when in water

- Assist in preparing and launching liferafts upon receiving instructions.

- Assisting passengers by being stairway guides

- In charge of a Muster Station as instructed

- Assisting in searching cabins for passengers and crew

- Assisting in guiding passengers to the lifeboats from the Muster Station

- Assisting moving disabled passengers

All of these emergency tasks place physical and mental demands on crewmembers. Seafarers must be able to perform these duties when required and to cope with the general, often stressful,situation.

Living at the working place

In addition, seafarers should be able to live and work closely with the same people for long periods of time and under occasionally stressful conditions. They should be capable of dealing effectively with isolation from family and friends and, in some cases, from persons of their own cultural background. Further information about living and working on board is available in other sections of Ch.4.

Any limitation to physical and mental capability may affect a seafarer’s ability to perform routine and emergency duties, for example, using breathing apparatus. Such limitations may also make rescue in the event of injury or illness difficult. In order to meet the physical and mental demands of working on board a ship, seafarers must undergo a medical examination prior to starting work on a ship, and at regular intervals after that. A satisfactory examination attests that the seafarer is medically fit to perform the duties that they are to carry out at sea. Further information on pre employment medical selection is available in Ch. 4.8.

C.3.10 Training and certification

The key to maintaining a healthy and safe shipping environment requires seafarers across the world to observe high standards of competence and professionalism in the duties they perform on-board. The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) 1978, as amended in 1995 and in 2010, sets those standards, provides a framework for training and certification and controls watch keeping arrangements. Its provisions not only apply to seafarers, but also to ship-owners, training establishments and national maritime administrations. A ship cannot sail from port if the officers and ratings on board do not hold the required STCW certificates. This is important if a seafarer needs to be evacuated from a ship, that other crewmembers hold appropriate certificates to administer first-aid and/or medical care before evacuation and allow the ship’s voyage and operation to continue before replacement crew arrive.

List of STCW Courses for Seafarers:

- Deck & Engine Officer Training Courses: STCW Deck and Engine Officer Courses, Leadership & Trainer, Assessment & Examinations, and Other Related Courses for Seafarers

- Basic Safety Training Program: STCW Basic Safety Training is required for seafarers employed or engaged in any capacity on board ship at all levels.

- Environment Related Training: Marine environment and energy efficient operations STCW courses for seafarers, management and other stakeholders

- Firefighting Courses: Basic and advanced firefighting courses under STCW for seafarers and designated personnel on shore.

- Maritime Safety Courses: Basic and advanced maritime safety courses under STCW for seafarers on passenger and merchant ships.

- Medical Courses: First aid and medical care courses and training under STCW for seafarers.

- GMDSS and Radio Courses: GMDSS technical and general operators courses and training under STCW for seafarers.

- Radar & Navigational Courses: Radar, ARPA, ECDIS, IBS & INS courses and training under STCW for seafarers.

- Maritime Security Courses: Maritime security courses and training under ISPS Code and STCW for seafarers and port security personnel.

- Ship Simulator Courses: STCW approved Bridge & Engine Room; LNG, Oil, & Chemical Tanker and other maritime simulator training courses for seafarers.

- Cargo Operations Courses: Liquefied Gas, Oil, & Chemical Tanker and other cargo operations training courses under STCW for seafarers.

Ship Survey, Port State Control & SAR Courses: IMO Ship Survey, Port State Control (PSC) & Search and Rescue (SAR) courses for shipping, maritime administrations & ports officers

Certificates

The term ‘certificates’ covers all official documents required under STCW. It includes certificates of competence, endorsements, certificates of proficiency, and any documentary evidence showing that a requirement of the convention has been met. Certificates are important as they provide documentary evidence that the seafarers’ level of maritime education and training, length of service at sea, professional competence, medical fitness and age all comply with STCW standards. Every party to the convention has to ensure that certificates are only issued to those seafarers who meet STCW standards.

Training

To obtain a STCW certificate seafarers first need to successfully complete a training programme approved by the issuing administration, and/or to complete a period of approved seagoing service. Most certificates will need a combination of both. Some of the training can be provided at sea, but for more specialised and longer courses, shore-based instruction is required. A certificate is issued once the seafarer has proved competence in and knowledge of the tasks covered by the certificate to the standards required.

Levels of competence

An officer (Master, deck and engine officer) must meet minimum requirements in respect of standards of competence in accordance with relevant chapters of the STCW Convention, seagoing service time, medical fitness and age. The officer should be in possession of a valid certificate of competence according to their rank and functions on-board.

Ratings fall under three general categories; those forming part of a watch, deck or engine, those who are not assigned watch keeping duties, and those undergoing training. A rating must meet minimum standards of medical fitness and of minimum age and competencies, if designated with watch keeping duties, in accordance with the relevant chapters of the STCW Convention. They must also have completed appropriate seagoing service time, if designated with watch keeping duties. Ratings who are not assigned watch keeping duties or those still undergoing training are not required to hold watch-keeping certificates.

The sea survival course is mandatory for all sea staff regardless of role.

Medical training of ship officers:

The STCW Code PART A Chapter VI provides the basis for medical training of ship officers. On the basis these requirements the IMO has produced a series of model courses:

- Model course 1:13 “Elementary First Aid”

This model course provides training in elementary first aid at the support level and is based on the provisions of table A-VI/1-3 of the STCW Code

- Model course 1:14 “Medical First Aid”

This model course provides training in elementary first aid at operator’s level and is based on the provisions of table A-VI/4-1 of the STCW Code.

- Model course 1:15 “Medical Care”

This two-volume model course provides training in elementary first aid at management level and is based on the provisions of table A-VI/4-2 of the STCW Code.

Officers who have the responsibility for medical issues on board must have completed all three courses. The first two deal mainly with safety issues, but also with the treatment of injuries. The theoretical knowledge of medicine and first aid obtained at these courses is limited. However, officers are taught to perform some important and potentially lifesaving procedures such as the immediate care of severe injuries and of unconscious persons, and the establishment of venous access. Such training is vital as no medical advice or equipment can replace the first aid given in the first minutes after an accident or an acute disease. More information on the training in medical care for seafarers is available in Chapter 5.3.

C.3.11 References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seafarer%27s_professions_and_ranks

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_cook

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_steward

http://seamansupport.com/ranks-merchant-shipping/

https://www.marineinsight.com/careers-2/a-guide-to-merchant-navy-officer-ranks/

https://maritimeoutlook.wordpress.com/2018/01/11/beginners-guide-to-merchant-navy-officer-ranks/

http://www.careersatsea.org/ratings-roles/

https://www.afcan.org/dossiers_reglementation/ism_p12_gb.html

IMO Train the Trainer (TTT) Course on Energy Efficient Ship Operation - Module 4 – Ship Board Energy Management

INFLUENCE OF SHIPPING COMPANY ORGANIZATION ON SHIP'S TEAM WORK EFFECTIVENESS Capt. Toni Bielić, Ph. D.

The relationships between seafarers and shore‐side personnel: An outline report based on research undertaken in the period 2012‐2016 - Helen Sampson, Iris Acejo, Neil Ellis, Lijun Tang, Nelson Turgo

STCW A Guide For Seafarers, Taking Into Account The 2010 Manila amendments - International Transport Workers’ Federation

Some Uses of Accident Data in Maritime Occupational Safety – Pekka Räisänen http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522162984.pdf

Guidelines on the medical examinations of seafarers - International Labour Office Geneva and International Maritime Organization

Emergency duties of seafarers - Stuart Greenfield, Maritime and Coastguard Agency, Maritime Health Seminar 2014

Effective ship maintenance strategy using a risk and criticality based approach - I. Lazakis, O. Turan, S. Alkaner & A.Olcer - https://pure.strath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/39330169/Lazakis_etal_IMAM2009

_ship_maintenance_strategy_using_a_risk_and_criticality.pdf

Accident prevention on board ship at sea and in port - International Labour Office Geneva - //www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@

safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107798.pdf">

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@

safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107798.pdf