VIVEK MENON with contributions from BOB BRIDGER and MARGARETHA HOLTENSDOTTER LÜTZHÖFT

C.2.1 Types of vessels

There are many types of vessels depending on the type or cargoes carried and/or its purpose. Vessels are built based on the requirements for transportation of particular commodities that differ from place to place, industry to industry and country to country.

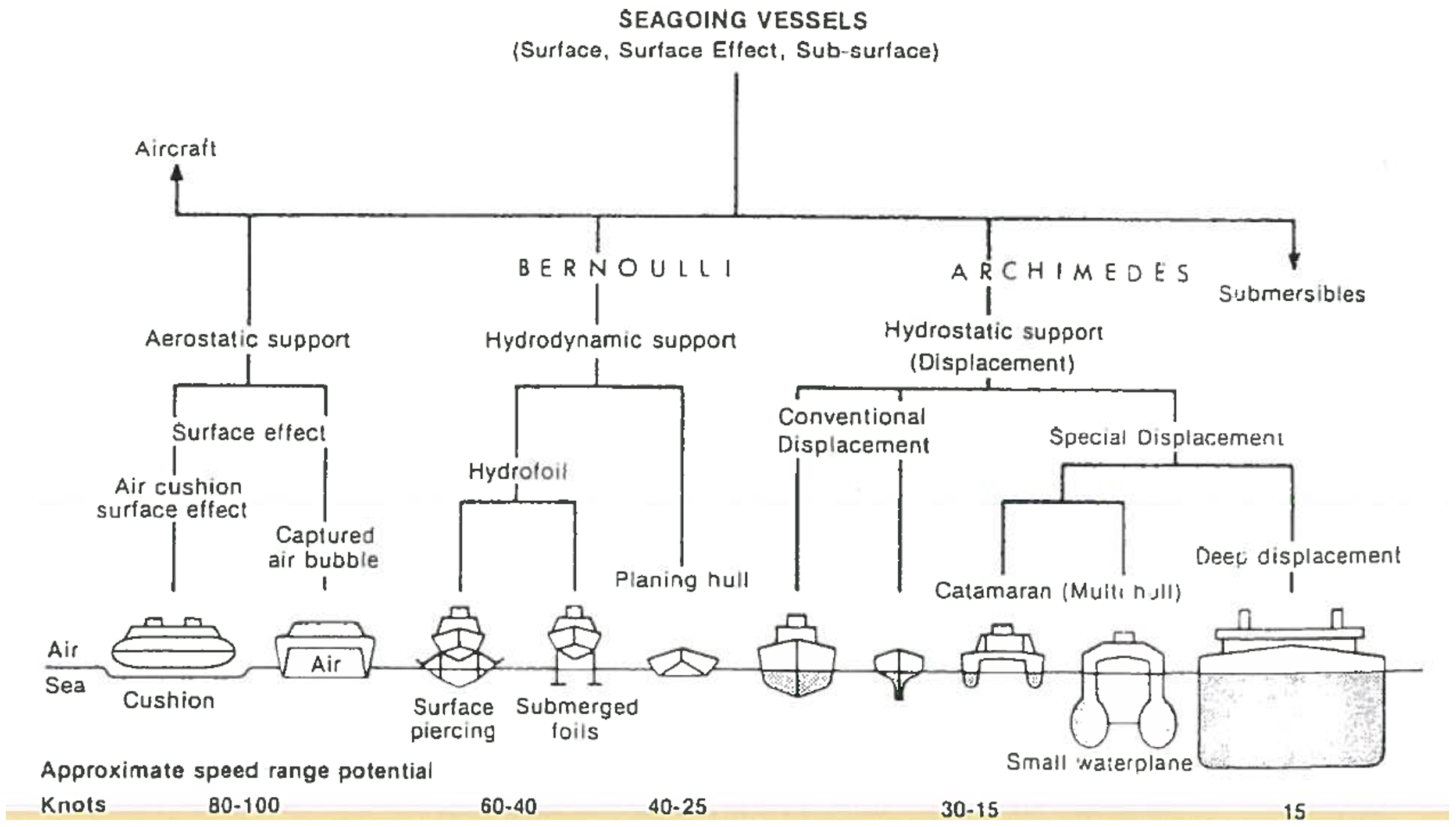

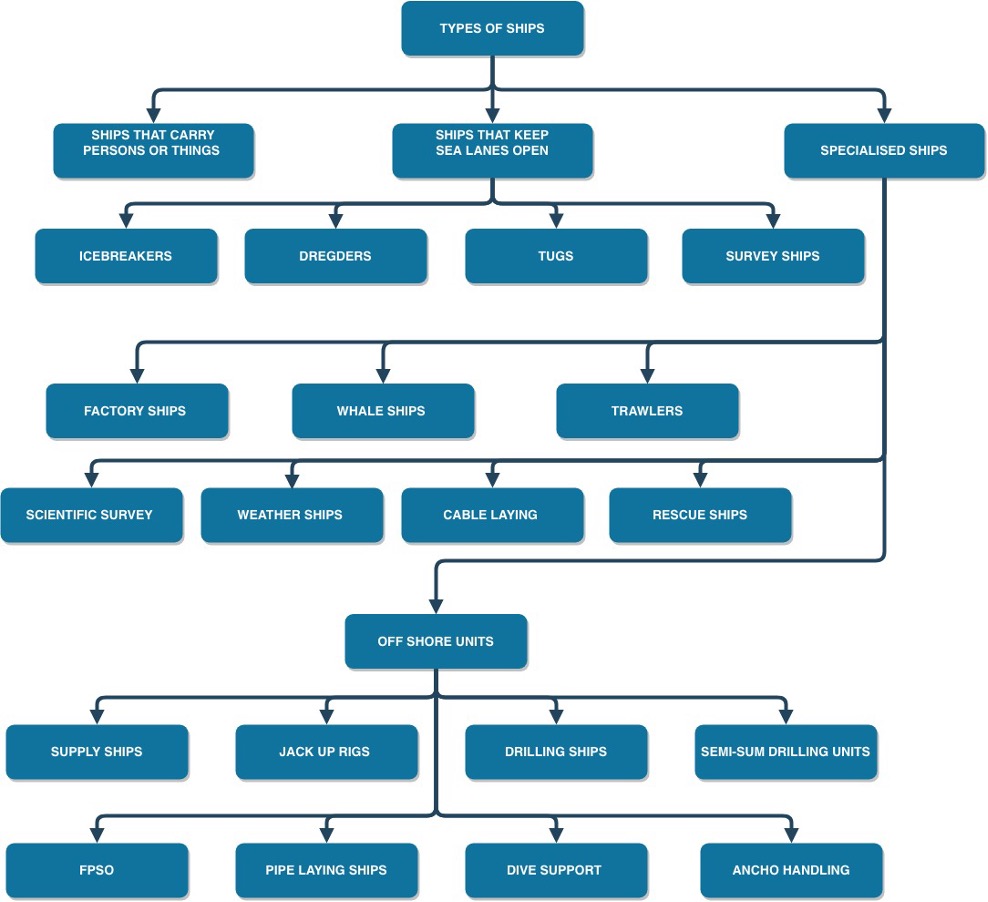

Vessel category

Vessels can be categorised on the basis of:

- Their mode of support on water

- Hydrostatically supported i.e. supported by force of buoyancy

- Dynamically supported i.e. supported partially by buoyancy and partially or fully by other forces (hydrodynamic or aerostatic)

In order for a vessel to obtain certain speed and thereby move distance a force needs to be exerted on the vessel. A propulsion system provides this force, which usually consists of an engine or turbine, gearboxes, propeller shaft and propeller. The design of the propulsion system varies depending on the type of vessel and primarily takes care of the different resistances that a vessel encounters, such as resistance caused due to friction, pressure, wave and air.

In addition, it is important to have an optimum underwater ship design in the form of minimum resistance for the vessels intended purpose.

- Function of the vessel - commercial vessels fall under three categories,

- vessels that carry persons or things,

- vessels that keep sea lanes open or the utility vessels, and

- specialised vessel

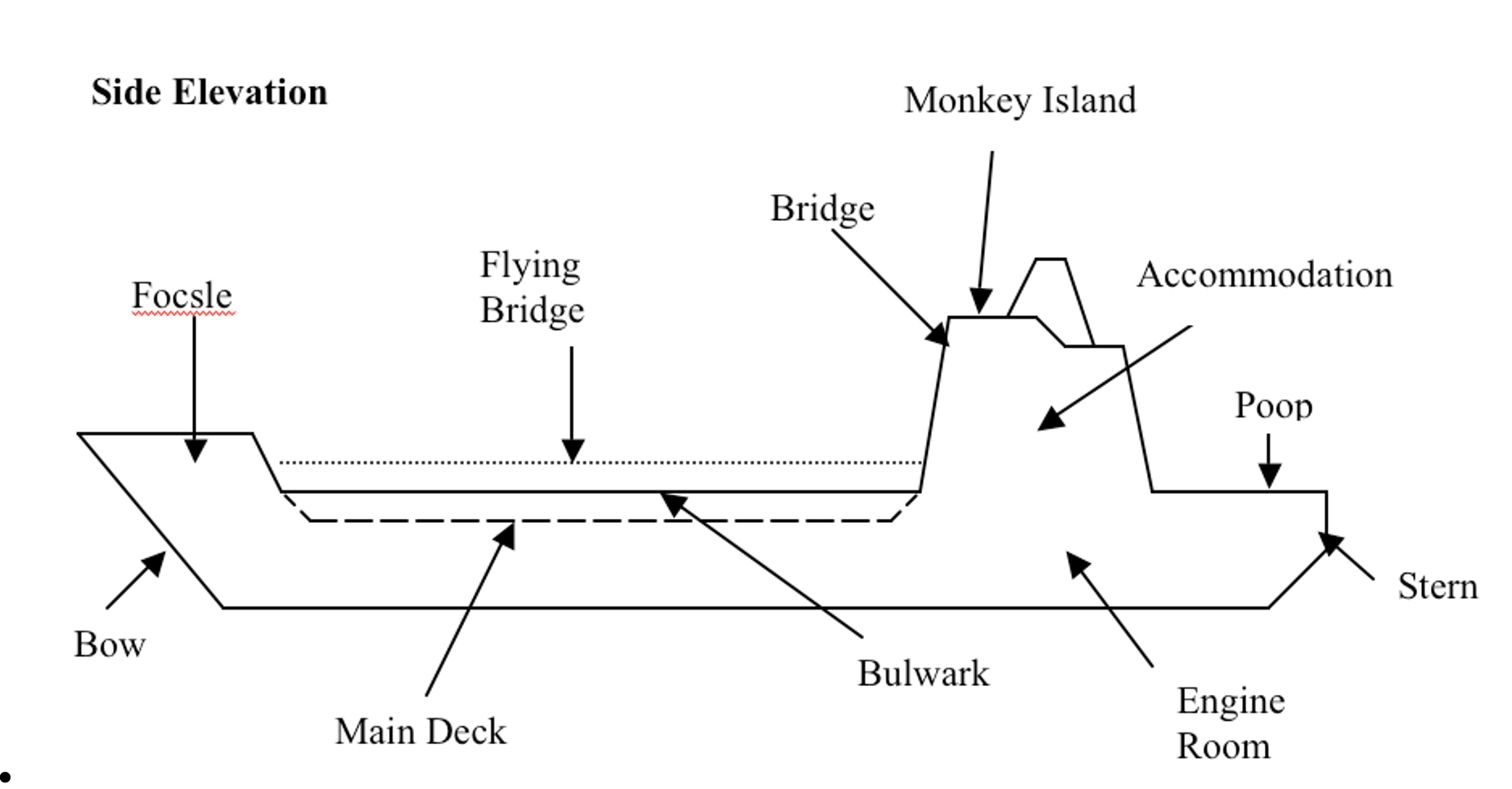

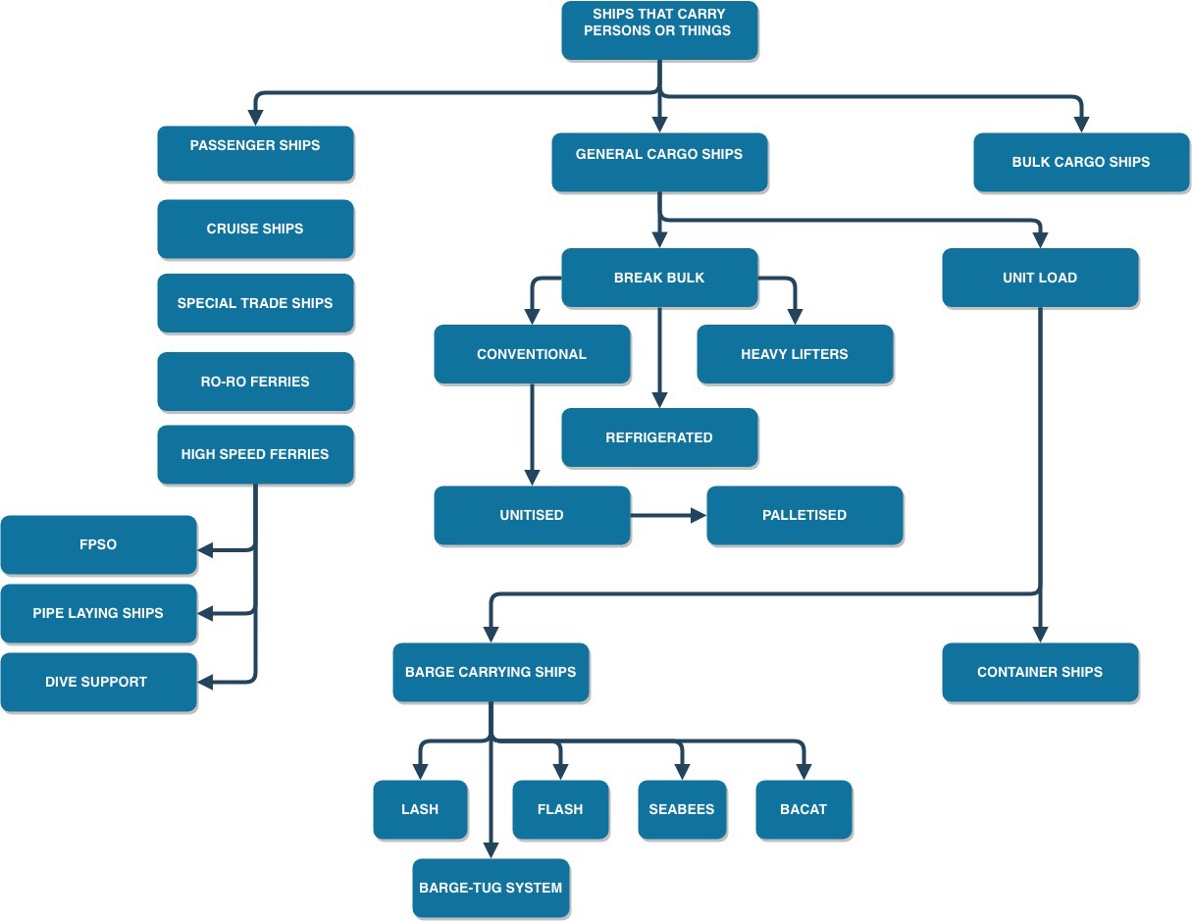

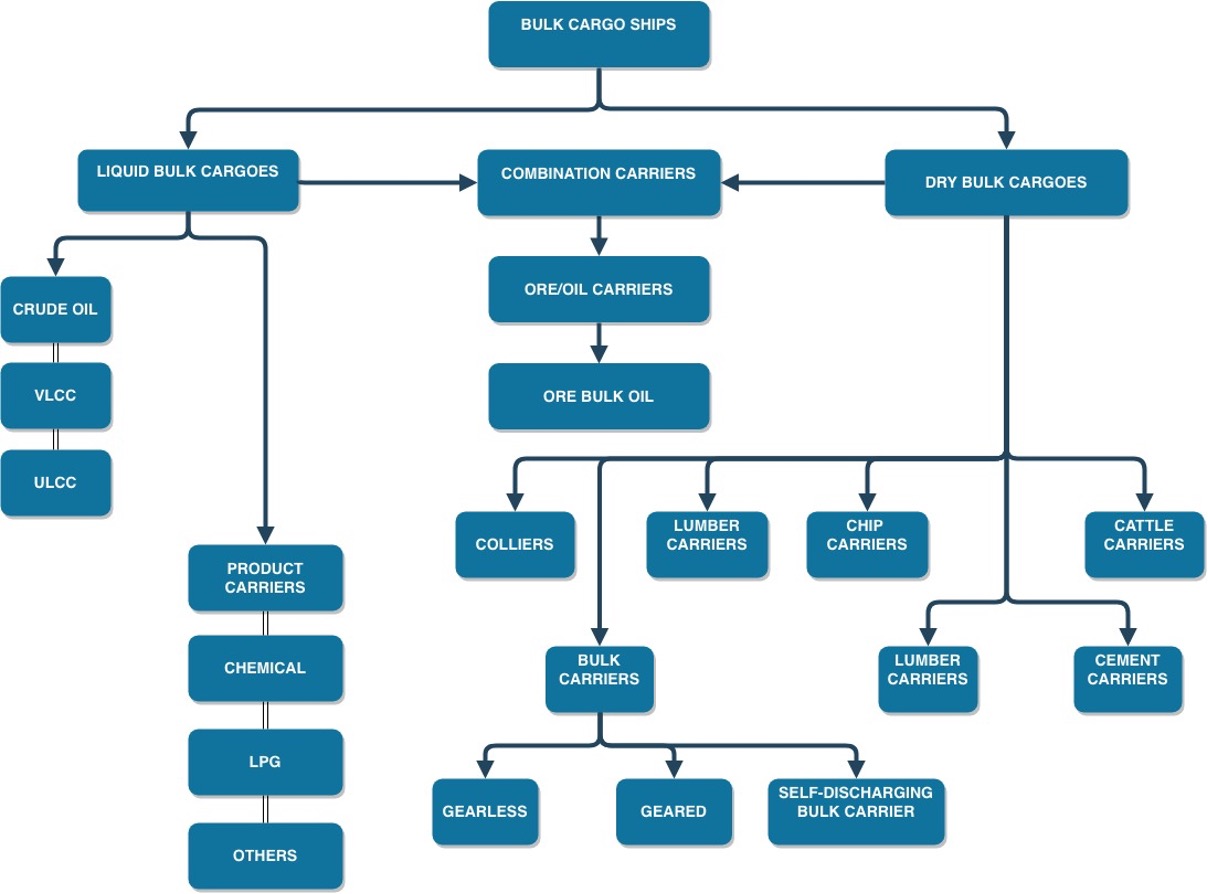

Figures 1-4 gives you an overview of the various types of vessel category.

Figure 1 Mode of transport

Figure 2 Mission of vessel

Figure 3 Vessels that carry persons or things

Figure 4 Bulk cargoes

C.2.2 Cargo carriers

General cargo ship

General cargo ships were once the predominant type of merchant ship. Generally small to medium size ships, they are usually equipped with their own cranes or derricks for handling their cargoes. This makes them versatile in terms of the cargo they can carry and the ports in which they are able to work.

Hazards specific to this ship type tend to relate to the large number of moving parts when working with cargo, such as wires, hatches and associated lifting gear. Other hazards include working with a variety of lashing gear, which may be heavy and require use in unstable positions. Working at heights is also a hazard when working such vessels.

Container ship

Container ships are characterized by the absence of cargo handling gear, reflecting the usual practice of locating the container-handling cranes at shore terminals rather than aboard ship. Unlike the tanker, container ships require large hatches in the deck for stowing the cargo, which consists of standardized containers usually either 20 or 40 feet in length. These ships may be small coastal ‘feeder’ vessels or vast inter-continental liners.

The stacks of containers on deck identify container ships. They are usually modern, fast and efficient which mean that their stays in port are normally short (6hours to 24 hours).

The main hazards on this type of vessel are heavy deck lashings that may be lying about the deck or fall from above and containers being lifted overhead. Many containers contain dangerous goods that can, occasionally, leak or cause other issues. Containers may also have toxic atmospheres from the use of fumigants such as methyl bromide or cyanide. Appropriate Personal Protective Equipment may be required by the crew.

Barge-carrying ships

An extension of the container ship concept is the barge-carrying ship. Here the container itself is a floating vessel, usually about 60 feet long by about 30 feet wide, which is loaded aboard the ship in one of two ways. Either it is lifted over the stern by a high-capacity shipboard gantry crane, or the ship is partially submerged so that the barges can be floated aboard via a gate in the stern.

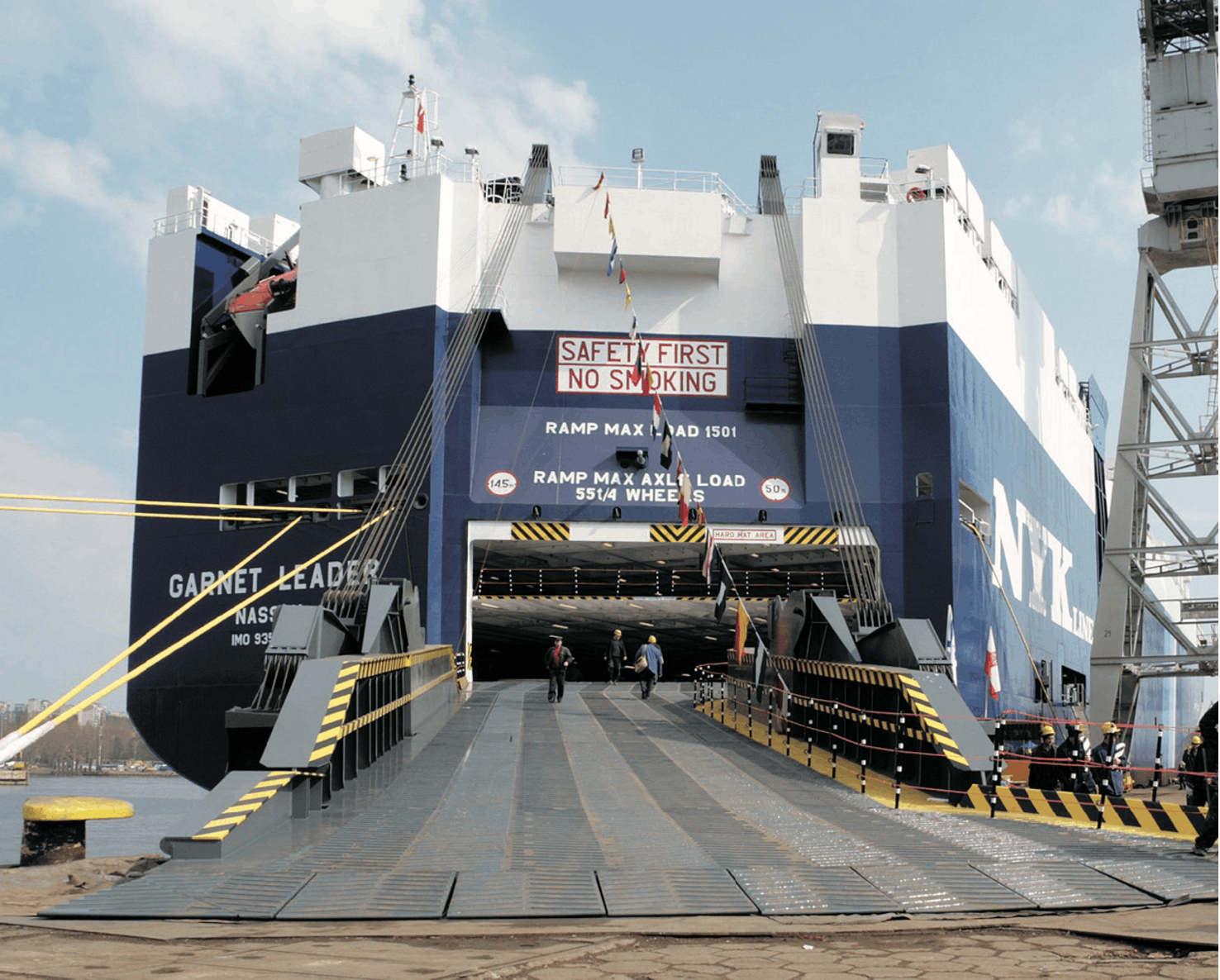

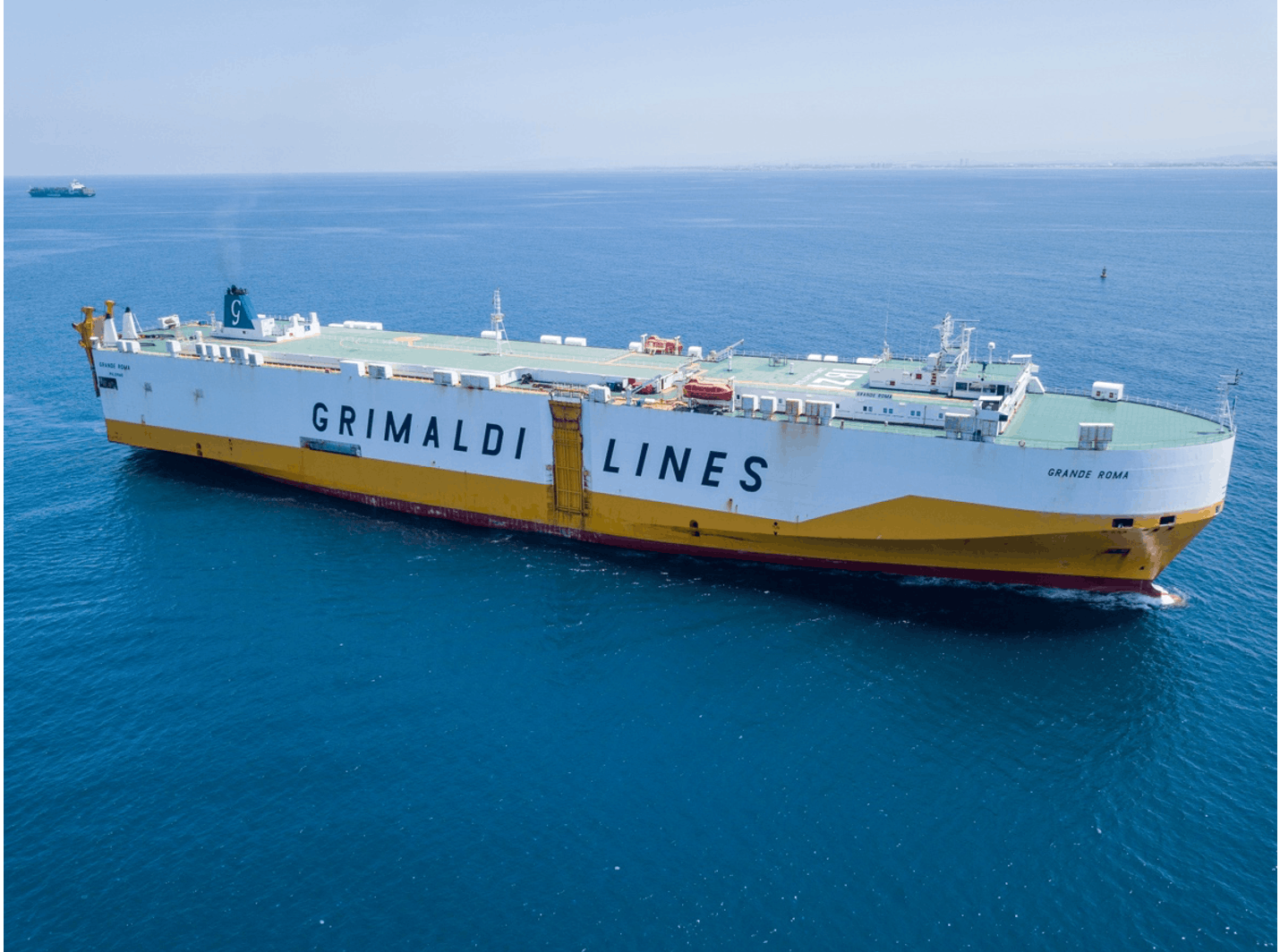

Ro-Ro ships

Ro-Ro stands for Roll on - Roll off. Roll-on/roll-off ships are designed for the carriage of wheeled cargo, and are distinguished by large doors in the hull (usually at the bow, stern or in some cases the ships side) and often by external ramps that fold down to allow rolling between pier and ship.

Huge car carriers, for example, employ this principle to transport cars between continents. Turnaround in port can be quite fast.

Moving vehicles, fumes from vehicles inside the ship, heavy lifting and working in physically wearing postures constitute some of the main hazards in this type of ship.

Dry Bulk carriers

Bulk Carriers usually carry unpackaged (i.e. ‘bulk’) dry cargoes, such as coal, grain and ores that are poured directly into the ships’ holds. Other forms of cargoes such as steel slabs, coils, pipes, are also carried on bulk crriers. These ships vary considerably in size from small coastal vessels to large ships, which carry tens of thousands of tonnes of cargo. They may be equipped with their own cargo handling cranes, but often rely on shore conveyors and cranes to handle cargo.

The primary hazard in these ships is loose material underfoot (e.g. piles of coal dust and particles), and large grabs operating overhead in the hatches. In addition, there are specific risks based on the cargo being carried, e.g. coal can lead to spontaneous combustion, lead ores can be associated with toxicity, wood chips can emit toxic gases (carbon monoxide), organic cargoes can lead to oxygen deficiency and soya as a cargo runs the risk of acting as an allergen.

Oil Tankers

Oil tankers carry oil, or oil products, in bulk.

The cargoes are pumped directly into or out of the ship’s tanks. Tankers have their own cargo handling pumps that are housed in a pump room low down in the ship. Tankers vary in size from small coastal vessels to vast ships where the crew sometimes use bicycles to get around the main deck!

The main hazard on a tanker is fire. Precautions must be taken to prevent smoking and avoid static or sparks. Equipment and clothing used on a tanker must be intrinsically safe (no mobile phones or ‘normal’ torches, for example) and anti-static (no ‘normal’ nylon jackets, steel tools, etc). These ships often bond to the quay by means of a heavy cable to prevent the build-up of static electricity. Tankers use inert gas to reduce the fire risk and this causes problems with tank entry or cleaning. In the event of an electrical storm, cargo work may be suspended.

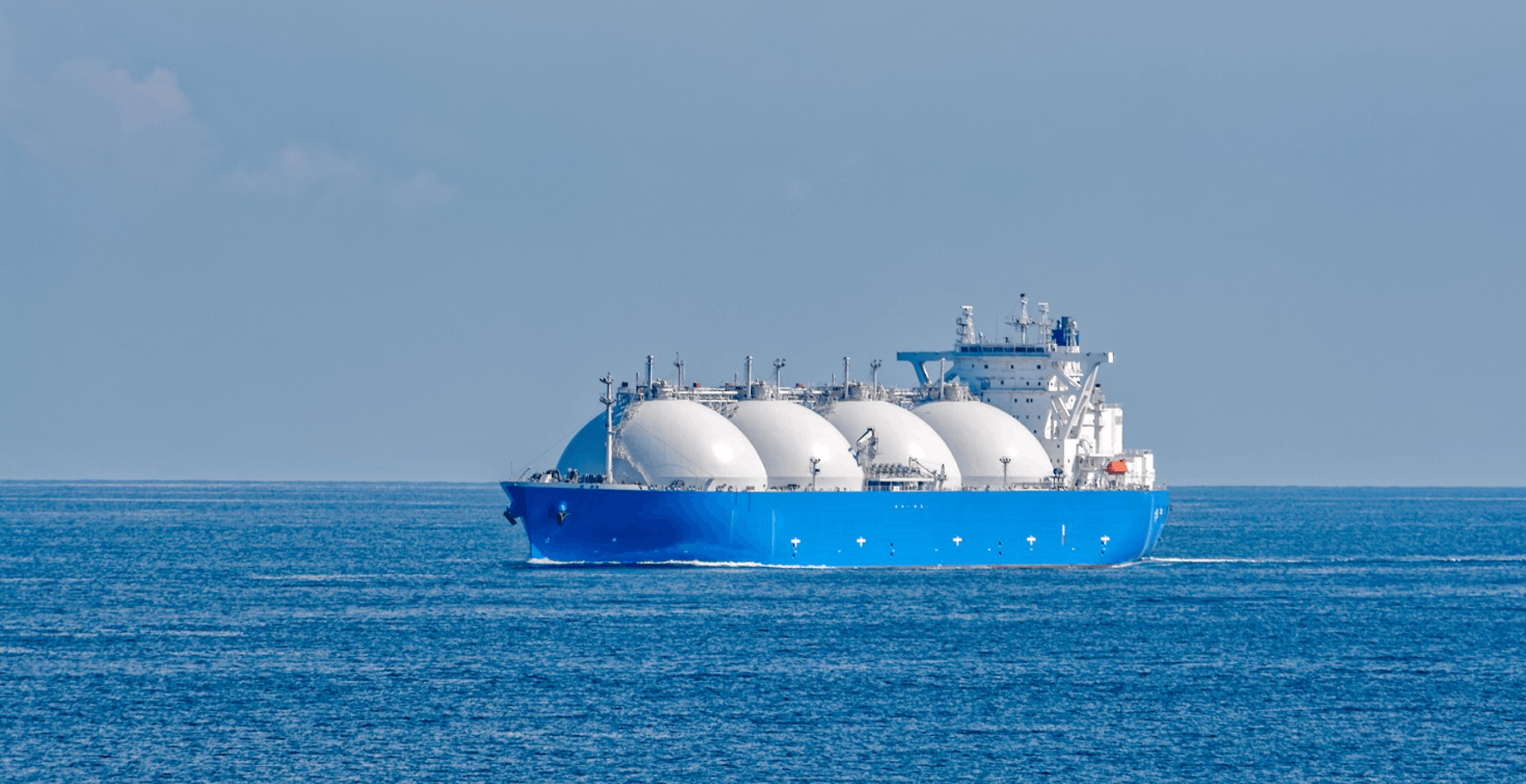

Gas Tankers

Gas tankers carry liquefied gas in bulk and vary in size from small coastal ships to huge vessels. Some of these gas tankers use their cargo for steam generated propulsion and as such as the only remaining commercial ‘steamships’. They fall into two main categories, those designed to carry liquefied petroleum gas (LPG, such as butane or propane) and those designed to carry liquefied natural gas (LNG – methane).

In both cases the gas is pumped directly into and out of the ship’s tanks. The gas remains in a liquid state by refrigeration, pressurisation, or a combination of these methods, depending on the design of the ship. There may be a plant on board to perform these functions.

The main hazard in these ships is the same as those for oil tankers, i.e. fire. Another hazard in gas tankers is that the cargo may be carried at very low temperatures (-163ْ C in LNG ships). This means that cargo pipelines and any spillages may ‘burn’ items in contact with them.

Chemical Tankers

Chemical tankers tend to be smaller, complex vessels with many cargo tanks (about 30). They are capable of carrying many different categories of chemicals in bulk and have individual tanks and cargo pipelines constructed from different material to cope with different cargoes.

The hazards in chemical tankers are similar to gas tankers, that is, fire and contact with the cargo. Some cargoes are intrinsically toxic and precautions need to be in place to manage any loss of containment or contamination of seafarers. In addition, chemical cargoes can be carcinogenic in nature and long-term low-level exposure to such cargoes can be hazardous. Between cargoes, tanks may need to be cleaned with strong acids or alkalis and these in turn may injure workers if protective measures are not used and/ or clothing is defective.

Other tankers include those designed to carry edible oils, molasses, etc.

C.2.3 Passenger carriers

Ferries

Ferries are vessels of any size that carry passengers and (in many cases) their vehicles on fixed routes over short cross-water passages. Vessels vary greatly in size and in quality of accommodations. Some on longer runs offer overnight cabins and even come close to equalling the accommodation standards of cruise ships, others offer rudimentary seating only. All vessels typically load vehicles aboard one or more decks via low-level side doors or by stern or bow ramps much like those found on roll-on/roll-off cargo ships.

A special type of ferry is the “double-ender,” built for shuttling across harbour waters with loading ramps at both ends. Special docks, fitted with adjustable ramps to cope with changes in water levels and shaped to fit the ends of the ferry, are always a necessary part of a ferry system of this type.

Figure 14 Ferry crossing Puget Sound, Seattle.© Dwight Smith/Shutterstock.com

Moving vehicles, fumes from vehicles inside the ship, heavy lifting and working in physically wearing postures constitute some of the main hazards in this type of ship. Additionally, there are risks associated to the management of large crowds.

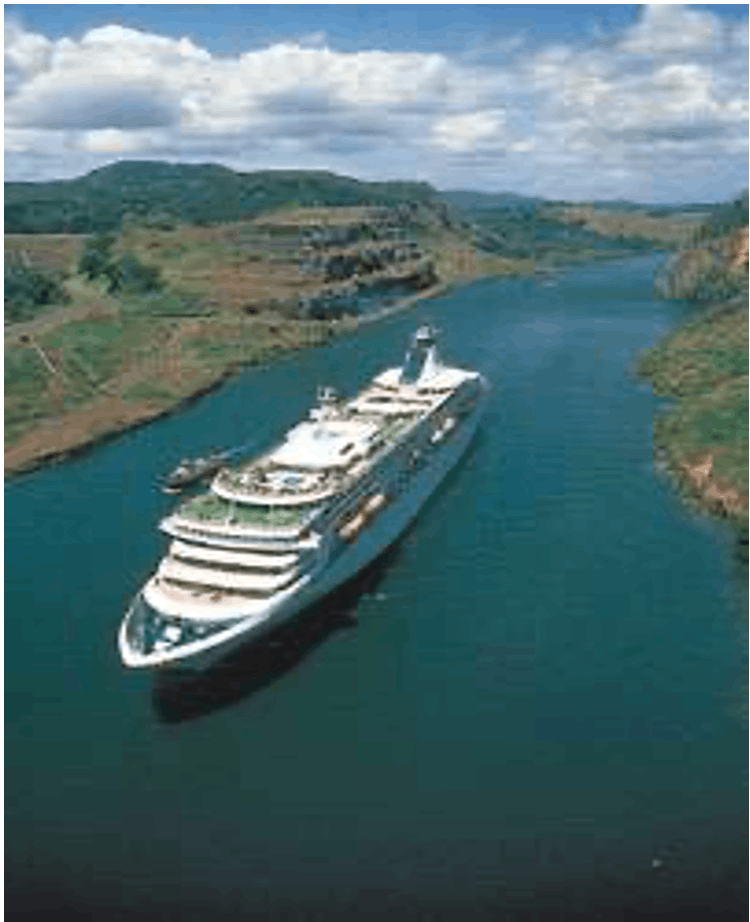

Cruise ships

Cruise ships are descended from the transatlantic ocean liners, which, since the mid-20th century, have found their services pre-empted by jet aircraft. Most of them are designed for large numbers of passengers (perhaps several thousand) and they are characterized by high superstructures of many decks. Since their principal routes lie in warm seas, they are typically painted white all over. Many cruise ships have stern ramps, much like those found on cargo-carrying roll-on/roll-off ships in order to facilitate the transfer of passengers to the launches and to serve as docking facilities for small sporting boats.

Heavy lifting and working in physically wearing postures constitute some of the main hazards in this type of ship. Additionally, there are risks associated to the management of large crowds

High Speed Craft

Another special type of ferry is a high-speed vessel that in many cases is of catamaran (twin-hulled) design. High speed craft are generally employed in short sea routes to compete with conventional passenger ferry traffic. They are usually smaller than traditional ships, may be mono or multi hull vessels and operate at speeds in excess of 40 knots in order to halve crossing times on most routes. However, they do not carry vehicles.

Hazards inherent in this type of vessel should be restricted to those that are unavoidable in ships, such as the gangway or storm steps. The demands on navigating officers of such vessels can be high, especially when in congested shipping lanes or complex channels because of the speed with which a serious incident can arise.

C.2.4 Service vessels

Tugs and tows

Tugs are towing vessels whose principal function is to provide propulsive power to other vessels. Most of them serve in harbours and inland waters and are small in size. Tugs may be used in port for pushing and pulling ships, manoeuvring in the harbour, or for towing structures and vessels at sea. They are normally powerful, compact vessels with specialised towing equipment on the aft deck.

The towing of massive drilling rigs for the petroleum industry and an occasional salvage operation (e.g. towing a disabled ship) demand vessels larger and more seaworthy than the more common inshore service vessels.

The primary hazard for visitors on tugs is that alleyways and stairs tend to be narrow and steep due to the space available. Furthermore, tugs use steel hawsers under tension and these can pose hazards to seafarers working on deck because of changing tow directions or tensions, from winding operations or from hawsers parting and uncoiling.

Icebreakers

Icebreakers are usually owned by government. They are not large in size, since no cargo is to be carried. However, icebreakers are usually wide in order to make a wide swath through ice, and they have high propulsive power to overcome the resistance of the ice layer.

Icebreaker ships are a special class of ships that are designed to break even thickest of the ice and make some of the most inhospitable paths accessible to the world, navigating through the ice-covered waters, for e.g. the Polar Regions. Ice-breakers have a strengthened hull to resist ice-covered waters, a special ice-clearing shape design to move or make a path forward and extreme power to navigate through sea ice.

The prime functions of an icebreakers include clearing the trade routes in the icy waters, especially during winters. Even though some newly constructed commercial and passenger vessels are designed to navigate through the icy waters, the seasonal ice conditions make it difficult for these vessels to manage themselves. Therefore, icebreakers escort these vessels to ensure safe and ease of navigation. In addition to clearing a passage for the commercial and passenger vessels, icebreakers are also widely used to support research programmes conducted in the Polar regions.

The primary hazard on board these vessels is ice. The crew working on board these vessels can be subjected to extremely low temperatures, severe weather conditions, ice crushing pressure on the hull which can lead to emergency conditions and icing of work surfaces.

Research vessel

Research vessels are usually owned by governments and are designed, modified, or equipped to carry out research at sea. The sole purpose for operating a research vessel is to provide a seaborne platform from which scientists can accomplish oceanographic research. Cranes and winches for handling nets and small underwater vehicles often identify them externally. They are not large in size, since no cargo is to be carried. Internally, research vessels are usually characterized by laboratory and living spaces for the research personnel.

Onboard these ships you will find a mix of ship’s crew and scientists and/or researchers. Usually the Master and Chief Scientist (or Researcher) are responsible for the safe operation of the vessel and for preventing pollution, and providing a clear line of communication between the operating crew and the research party respectively.

Conducting research at sea is inherently risky with exposures to various conditions depending on the type or research and time spent at sea.

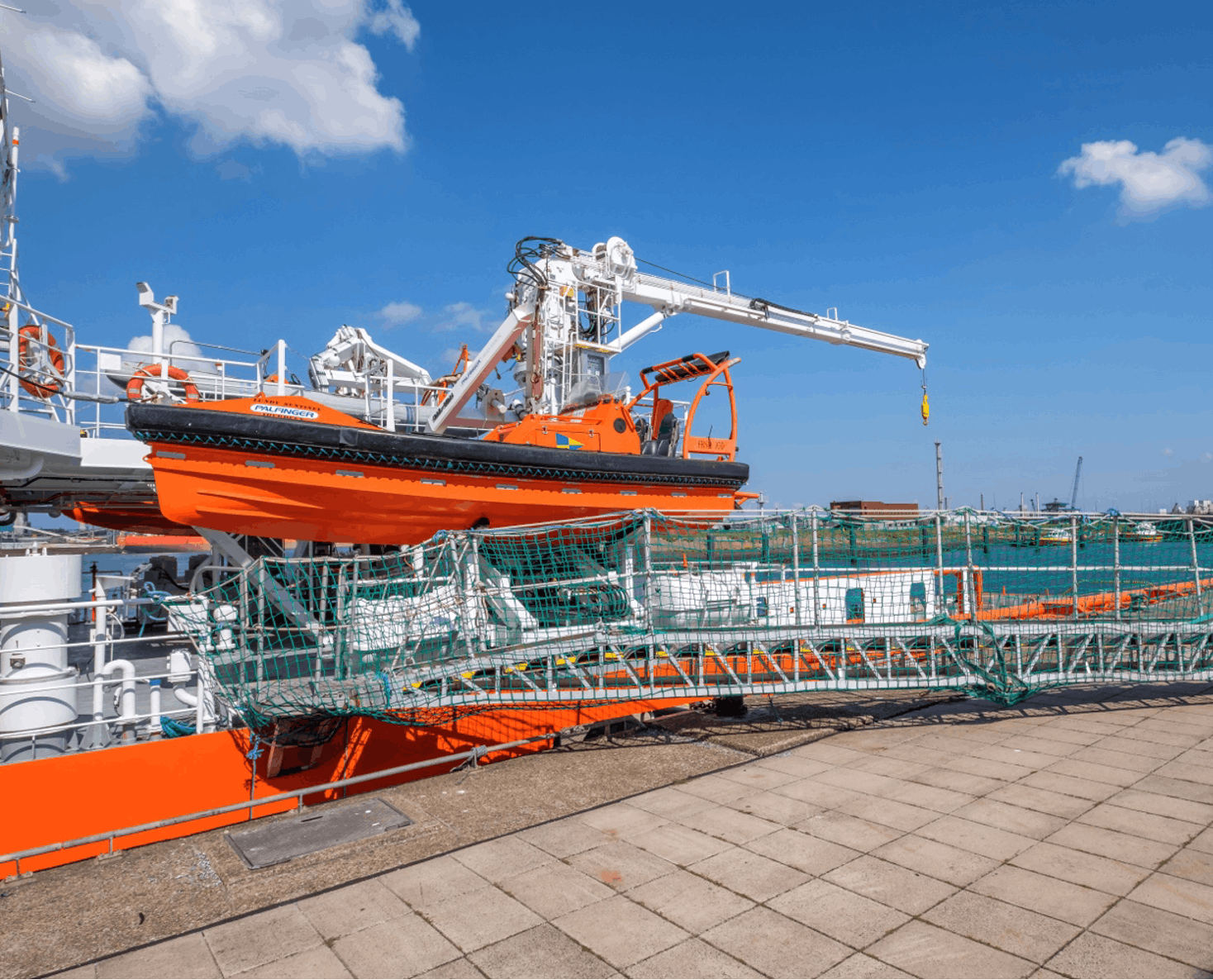

Supply & Stand-By Vessels

Supply vessels and stand by vessels work in offshore oil and gas fields. Supply vessels carry supplies to and from offshore installations on, on a flat deck at the aft end of the ship and in tanks below deck.

Stand-by vessels wait near to the offshore fields to ‘guard’ the fields against traffic which may stray too close to the offshore installations and to respond in the event of an emergency in the field.

Hazards associated with this type of ship are those connected with working cargo, such as gear about the deck and goods moving overhead.

Fleet Auxiliary/Naval logistic support

The ‘Auxiliary’ Fleet is usually part of the merchant navy and employs civilian seafarers whilst supporting the Navy in carrying supplies and stores for the warships.

The Auxiliary fleet, therefore, has a variety of ship types, from tankers to dry cargo ships that undertake specialist work such as replenishing warships at sea, or helicopter operations. They may also be used independently, for instance, in humanitarian relief missions.

The United States’ auxiliary fleet is known as Sealift Command.

Hazards in these vessels are similar to those for other ships of the type, e.g. a tanker. In addition, they may be working in war zones or close to areas of conflict and so be at risk of attack.

Warships and Military Vessels

Figure 23: Credit SteveAllenPhoto iStock

Warships and military vessels, such as those of the Navy, Army and Air Force, are part of the fighting forces and manned by service personnel, rather than civilians.

Warships undertake a variety of roles including defence, security and PR/diplomatic visits around the world, representing their government’s interests.

C.2.5 Industrial ships

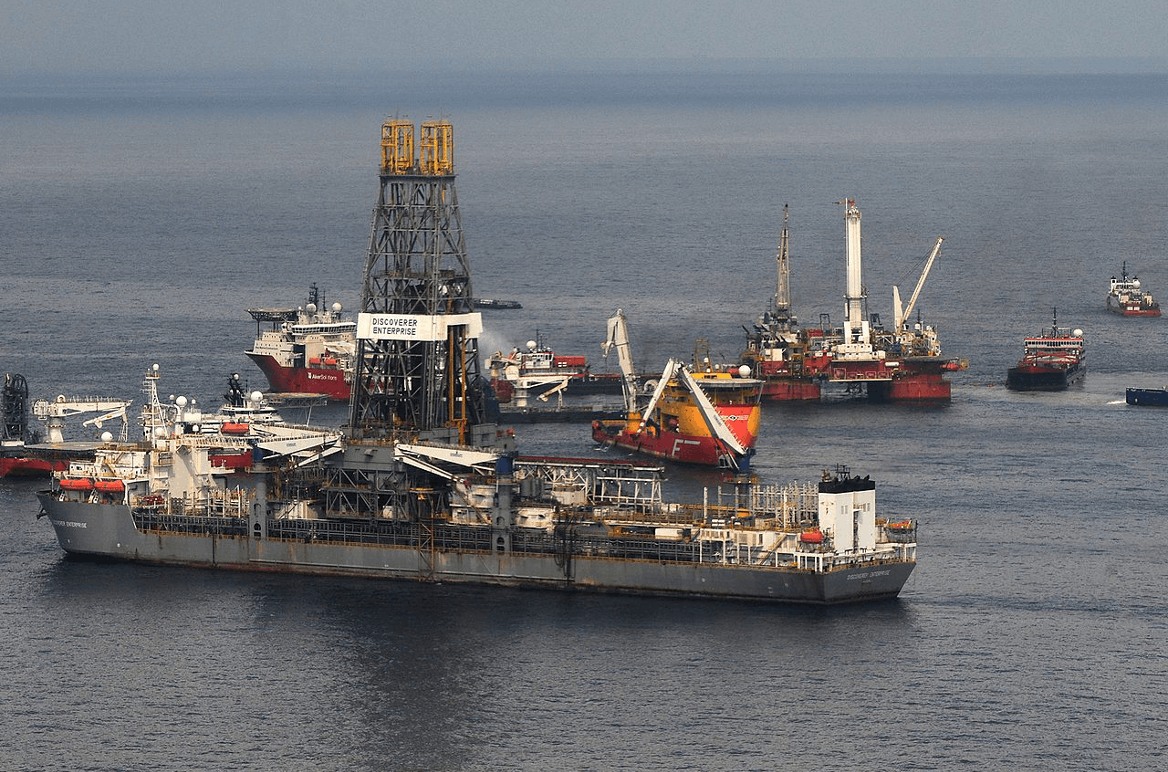

Drill ships

A drillship is a merchant vessel designed for use in the exploratory offshore drilling of new oil and gas wells or for scientific drilling purposes. In more recent years, the vessels are used in deepwater and ultra-deepwater applications, equipped with the latest and most advanced dynamic positioning systems.

Working onboard drillships that operate in deep waters, poses various types of hazards due to weather and operational conditions. For e.g. long work hours and little rest, poses risk of accidents. Some other examples of risks are:

Amputations, which may occur when hands or feet get caught in hazardous machinery.

Fall injuries, often caused by unsecured ladders, slippery stairways, and crowded platforms.

Chemical exposure due to oil drilling operations produce high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide, and prolonged exposure can cause respiratory distress, paralysis, and cancer.

Explosions and fires due to the highly combustible nature of petroleum, fires and explosions are a constant and serious threat. These accidents can cause severe burns and respiratory distress from the inhalation of smoke and toxins.

Fish processing vessel

A factory ship, also known as a fish processing vessel, is a large ocean-going vessel with extensive on-board facilities for processing and freezing caught fish or whales. Modern factory ships are automated and enlarged versions of the earlier whalers and their use in fishing has grown dramatically. Some factory ships are equipped to serve as a mother ship to a number of smaller fishing vessels.

Hazards found in different types of fishing operations are very similar and the levels of risk arising from specific hazards may vary between types of vessels. Compared to inshore fishing vessels, fish processing vessels use heavier machinery, more electricity, have more confined spaces, and are at sea for much longer periods. The most common types of work that are known to be high risk activities for the safety and health of crew members are:

- the winch, cables, ropes and otterboards[1], which are clear causes of occupational injuries;

- tasks associated with fishing operations, such as shooting or hauling in the net, are responsible for

the majority of falls overboard and accidents;

- lighting and visibility in the handling and transit zones is frequently inadequate; and

- the noise to which crews are exposed, even in the rest area, is often at levels regarded as dangerous, particularly for those crew members working in the engine room.

Fishing Vessels

These are usually very hard-working ships that specialise in catching fish. They are often very small compared with merchant ships and fall into two main types:– Trawlers, which tend to have large stern mounted structures designed to handle the nets dragged astern of the ship as she makes way at sea, or Drifters, which set long nets that lie in the water before stopping to drift with the tides/current.

Hazards include the large amount of gear that may be lying about the slippery decks.

Fishermen may spend days at sea often with little sleep, working in worse conditions than most seafarers do. The crew may be suffer from fatigue because of the commercial pressures to keep fishing until there is a full catch. Where fish processing is done on board there are also additional risks, as above. Fishing vessels travel into more and more remote waters in their search for a good catch, for example, the Barents Sea. This increases the risks from bad weather etc and also means that it is more difficult to render assistance if necessary.

A distinct set of problems arise in the coastal and artisanal fishing sectors where small boats are used, and formal employment is often replaced by a profit-sharing agreement among the crew. More information on the fishing industry is available in Ch. 3.2.5.

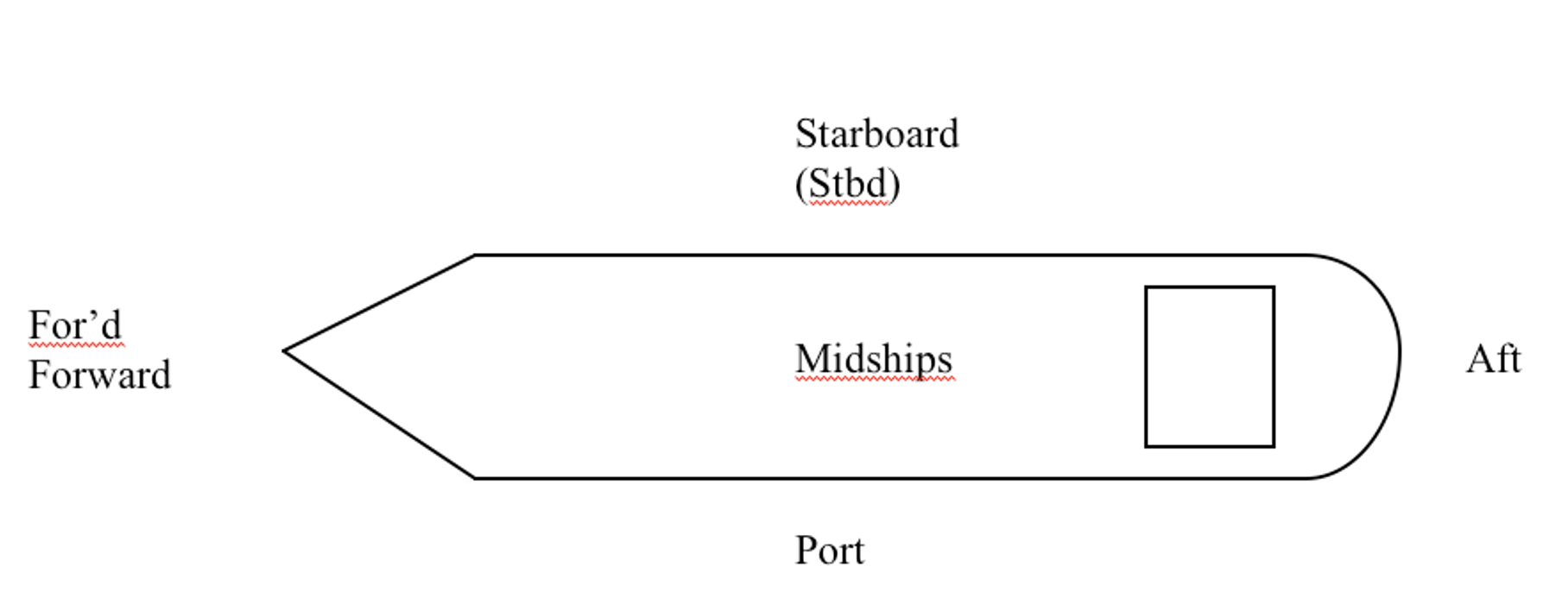

C.2.6 General terms

Terms and names used on board can vary from company to company and ship to ship, but the following will provide a reasonable basis for understanding of some shipboard terminology.

General Layout of vessel

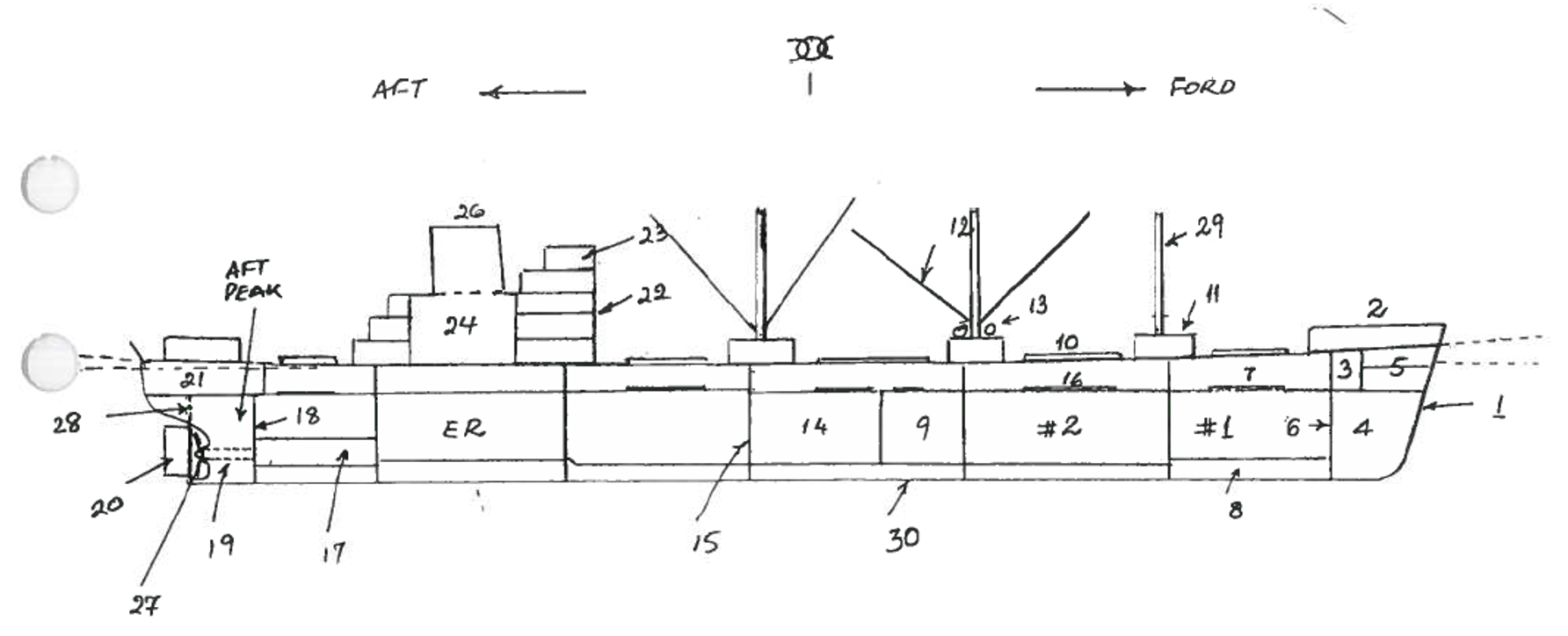

Figure 27 General Layout

1 | STEM | 16 | #2 TWEEN DECK HATCH AND COVER |

2 | FORECASTLE | 17 | SHAFT TUNNEL |

3 | CHAIN LOCKER | 18 | AFT PEAK BULKHEAD |

4 | FORE PEAK TANK | 19 | STERN TUBE |

5 | FORE PEAK STORES | 20 | RUDDER |

6 | COLLISION BULKHEAD | 21 | STEERING GEAR ROOM |

7 | TWEEN DECK # 1 | 22 | SUPER STRUCTURE |

8 | DOUBLE BOTTOM TANK | 23 | BRIDGE |

9 | DEEP TANK | 24 | ENGINE ROOM CASING |

10 | HATCH AND COVER | 25 | POOP DECKS |

11 | MAST HOUSE | 26 | FUNNEL |

12 | DERRICK | 27 | PROPELLER |

13 | WINCH | 28 | RUDDER POST OR STOCK |

14 | LOWER HOLD #3 | 29 | MAST |

15 | TRANSVERSE BULKHEAD | 30 | KEEL |

Basic definitions of selected terms

· Accommodation | · block of superstructure containing the cabins, mess, bridge, etc |

· Alleyway | passage or corridor |

· Amidships (or midships) | · middle of the vessel |

· Bow | · forward/front end of the ship |

· Bridge/Navigation Deck · (known as ‘The Bridge’) | top deck of accommodation |

· Bulkhead | · a wall |

· Bulwark | · solid parapet around the deck (usually the main deck) |

· Control Room | · the engine room control centre |

· Deck | · a floor |

· Deckhead | · a ceiling |

· Flying Bridge or Catwalk | · raised walkway on main deck (usually on tankers) between accommodation and focsle and/or poop |

· Focsle | · (from Fore Castle) forward mooring deck |

· Galley | · the kitchen |

· Heads | · toilets |

· Main Deck | · open area between accommodation and focsle and/or poop |

· Mess Room (or ‘The Mess’) | · dining room. Often one for officers (known as the saloon) and one for crew (known as the crew mess) |

· Monkey Island | · open deck on top of the bridge |

· Muster Station | · place at which personnel gather in emergency |

· Poop | · aft mooring deck |

· Port side | · left hand side looking forward (shows a red side light) |

· Ship’s Office or Cargo Control Room | · centre for ship’s operation in port |

· Starboard | · right hand side looking forward (shows a green light) |

· Stern | · after (aft)/back end of the ship |

· Storm Step | · raised sill in way of doors (to prevent ingress of water) |

· Wardroom | · the officer’s bar |

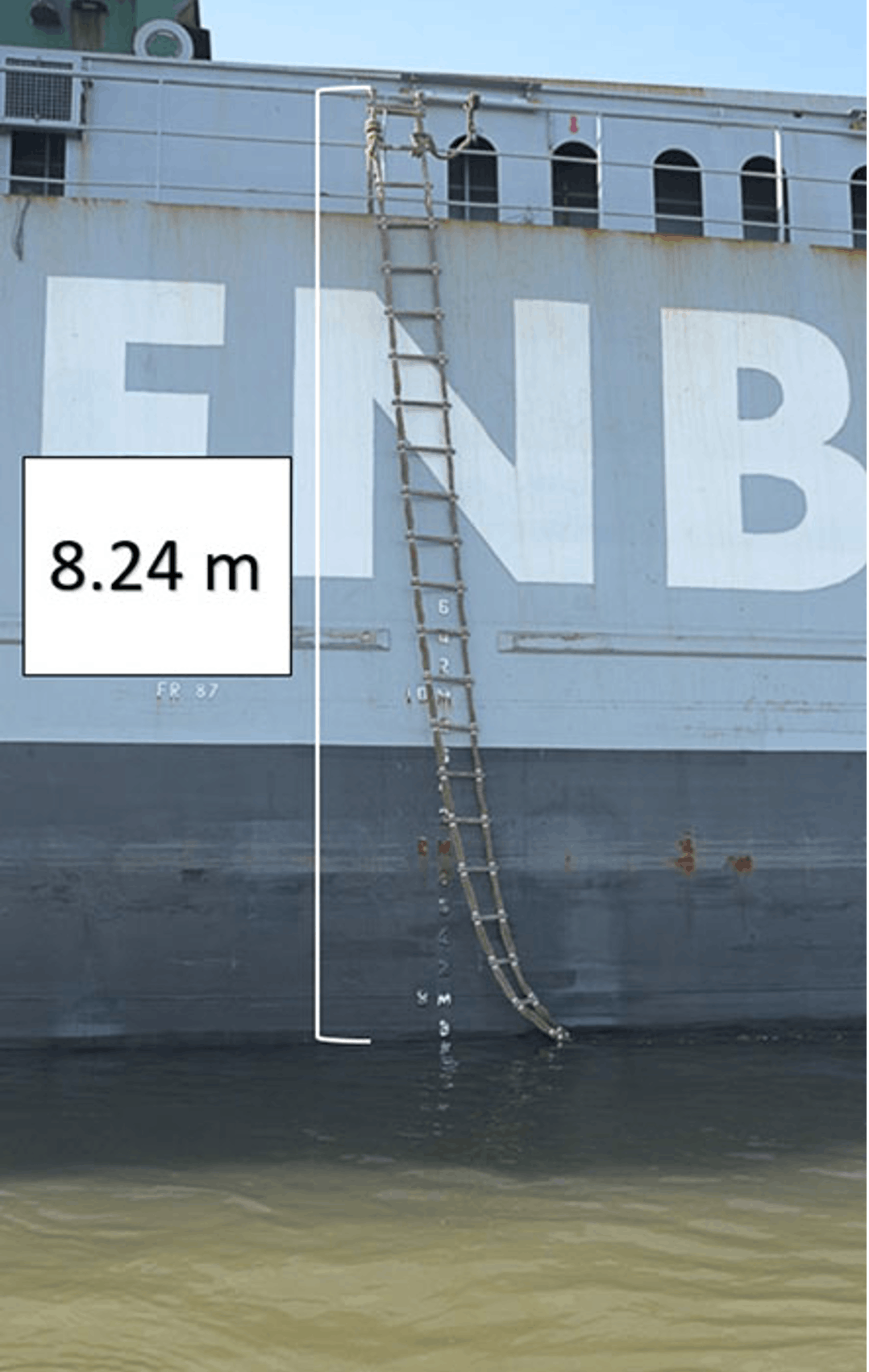

C.2.7 Access to vessels

There are many types of access systems to vessels, and they pose various hazards depending on the type of rigging and location. These hazards are usually associated to incorrect rigging or otherwise in a poor condition and dangerous working practices. There is a constant risk of serious injuries (or deaths), including drowning caused by falls from gangways or embarkation ladders.

Gangway – means of access to a ship, normally set at right angles to the vessel, secured to the ship’s deck at one end and resting on the quay at the other

Figure 28: Credit Frank Cornelissen - iStock

Accommodation Ladder – means of access to a larger ship. It is ship’s gear and normally a permanently rigged ‘stairway’ onto vessels

Figure 29: Credit- UK MAIB

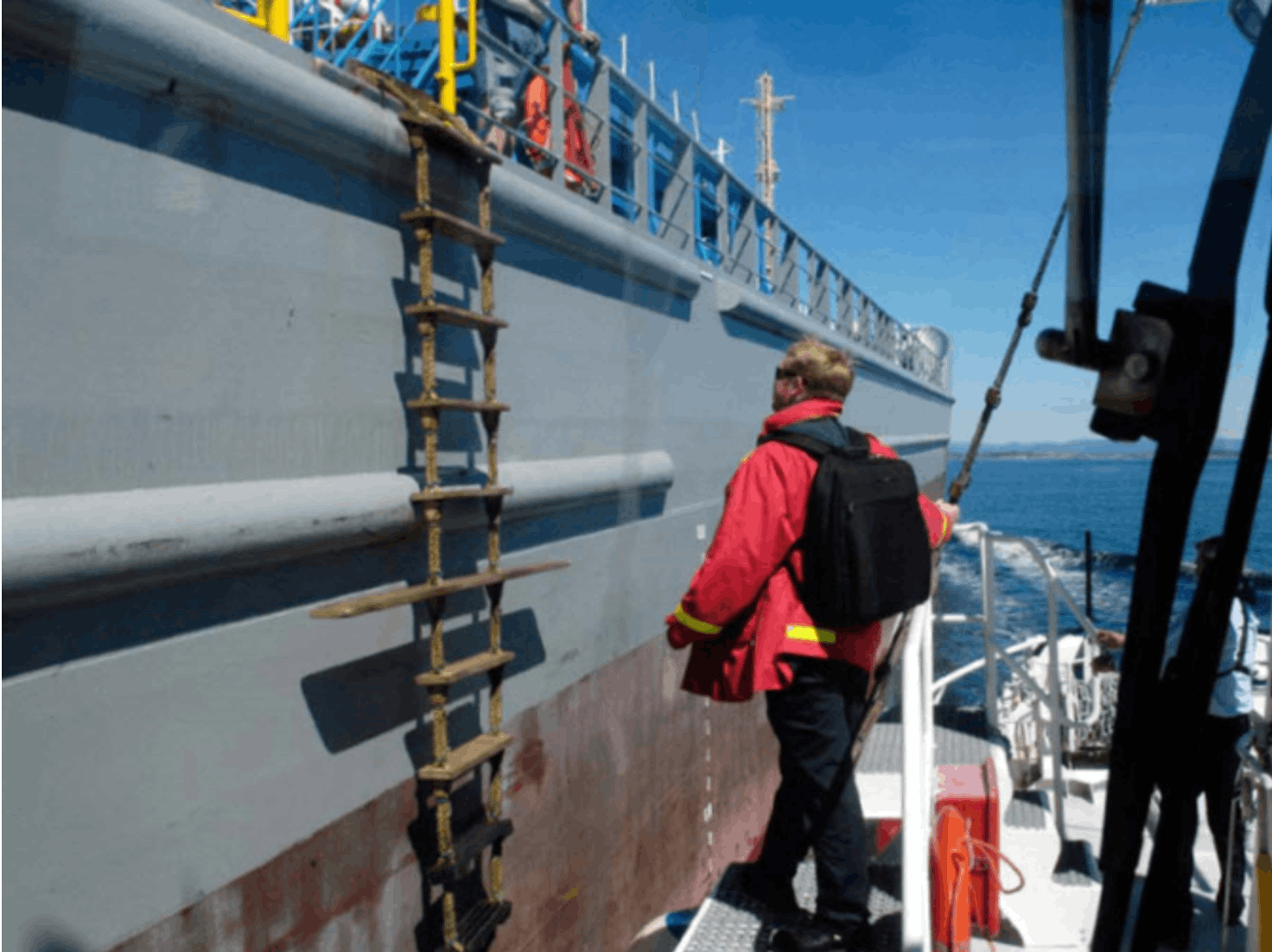

Pilot Ladder – a substantial rope ladder usually lying against the ship’s side.

It is used primarily for embarking and dis-embarking of pilots.

Additionally it may be used during crew changes when other ladders cannot be used.

Figure 30: Credit Gard Alert: Pilot transfers – still a risky business

Jacobs Ladder – a lighter, ‘portable’ rope ladder

Figure 31: Credit The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB)

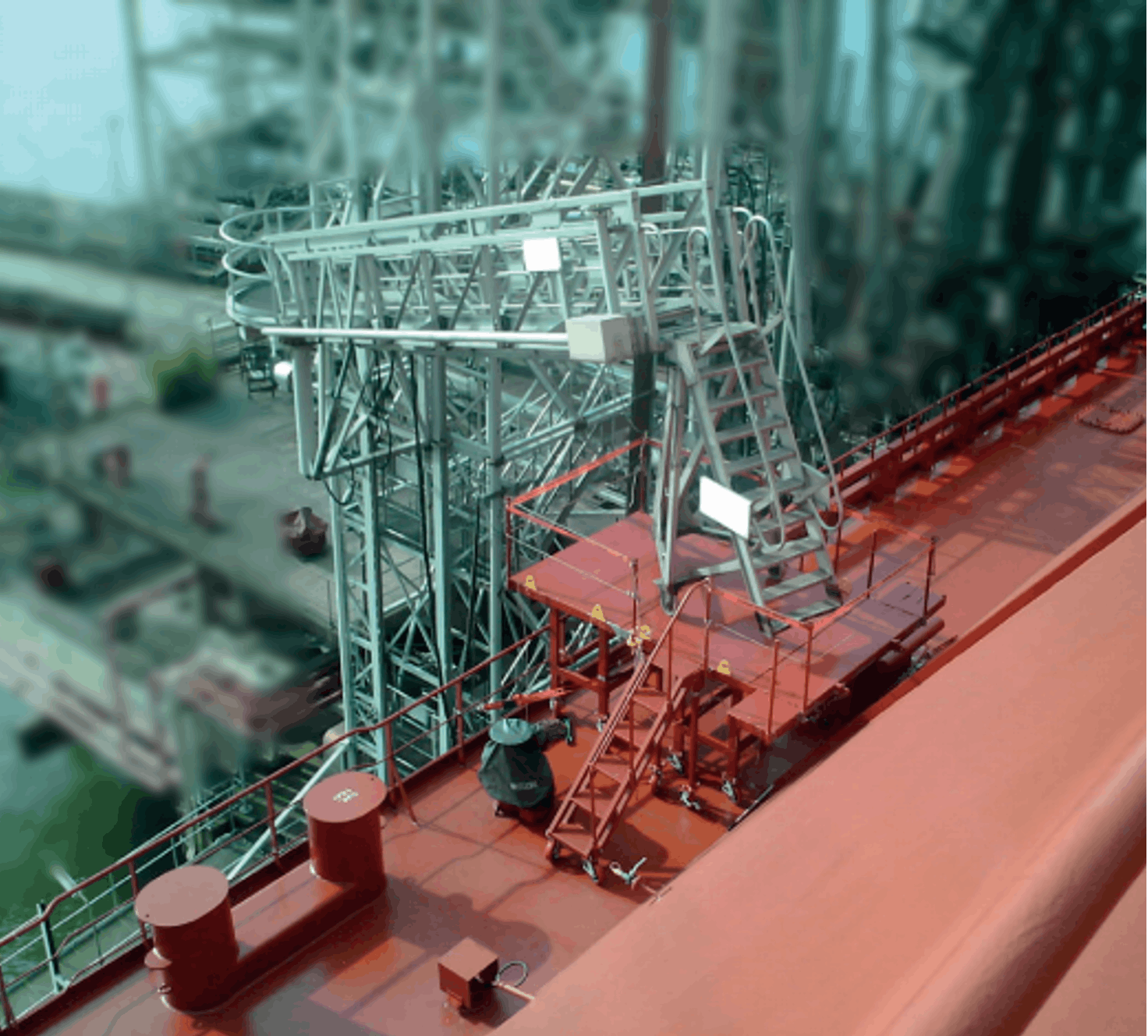

Tower – a rigid, shore-based structure incorporating a stairway up to a platform upon which a ‘gangway’ stretches to the ship

Figure 32: Credit The Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGTTO)

Jetty Ladder – a vertical metal ladder built into a jetty to provide access to craft lying below the level of the jetty

Figure 33: ⓒ 2020 Trelleborg Marine and Infrastructure

Link span – a heavy shore structure over which vehicular traffic gains access to vessels (such as ferries)

Figure 34: Credit MacGregor is part of Cargotec Corporation ©Cargotec 2020.

Ramp – may be bow, stern or side mounted on a ship to allow vehicular access

Figure 35: Credit © 2021 Wärtsilä

References

- MUNRO-SMITH, R. Elements of Ship Design. London; Marine Media Management; 1975

- MUNRO-SMITH, R. Ships and Naval Architecture. Institute of Marine Engineers; 1973

- Muckle W. Naval Architecture for Marine Engineers. Butterworth & Co (Publishers); 1975

- Thomas Charles Gillmer, Bruce Johnson Introduction to Naval Architecture. Naval Institute Press; 1985.

- Stokoe E. A. Naval Architecture for Marine Engineers. Thomas Reed; 1973.

- Klaas van Dokkum. Ship Knowiedge A Modern Encyciopaedia. DOKMAR; 2003

[1] Otterboards are used to keep the net open and may be made of iron, wood, or both. They may be oval, rectangular,

hollow or solid.