G.2.1 Blood or bodily fluids cluster

Potential hazards for blood-borne infections and sexually transmitted diseases include accidents and injuries, unsafe medical care provided to seafarers in ports in highly endemic areas, accidental injuries during medical procedures on board, unsafe blood transfusions, tattooing, piercing and unprotected sex.

Seafarers have traditionally been seen as a special risk group for acquiring and spreading sexually transmitted diseases, as indicated by the Brussels International Agreement of 1924 which requires state parties to provide free medical services to merchant seamen for the treatment of syphilis, urethritis of any aetiology, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguineale and any other venereal diseases (1).

In 1993 the common committee of the International Labour Organization and the World Health Organization identified Hepatitis B and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection / Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome as infectious diseases against which there should be provisions for guidance on prevention (2).

The Maritime Labour Convention 2006 emphasizes the need for HIV/AIDS prevention targeted at merchant seamen (3).

The International Maritime Health Association and the International Trade Federation issued a statement in 2008 in which the organizations advocate against selection for employment based on HIV status (4).

Despite widespread Hepatitis B, C or HIV testing as part of pre-employment examinations, there are no valid data concerning HIV or Hepatitis B /C prevalence in seafarers.

[1] World Health Organization. International Agreement of Brussels 1924. In: World Directory of Veneral Disease Treatment Centres at Ports. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO, 1972.

[2] International Labour Organization. Joint ILO/WHO Committee on the health of seafarers. Seventh session. Geneva, 10-14 May 1993. Report. Geneva: ILO, 1993. (JCHS/7/D (Rev.).

[3] International Labour Conference. Maritime Labour Convention 2006. Geneva: ILO, 2006-. https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/maritime-labour-convention/lang--en/index.htm, last access 14.2.2022

[4] The International Transport Workers’ Federation. Challenging HIV/AIDS in transport. Parris K, ed. Agenda 2008;(2). https://www.itfglobal.org/media/819789/hiv_survey.pdf, last access 14.2.2022

G.2.2 Risk assessment

Potential hazards for the spread of blood-borne infections and sexually transmitted diseases include:

- accidents and injuries,

- unsafe medical care provided to seafarers in ports in highly endemic areas,

- accidental injuries during medical procedures on board,

- unsafe blood transfusions,

- broken skin and skin lesions

- tattooing, piercing and

- unprotected sex.

G.2.3 Risk management

There is a marginal risk of transmission of blood-borne diseases from living and working together on a ship. However, medical care and first aid pose more specific risks of transmission from possible blood contact. Consequently, in the individual risk assessment at a PEME, and during the pre-travel counselling of seafarers, several risk factors for acquiring such infection need to be addressed:

- Risk of infection during first aid and medical care by nautical officers on board,

- Risk of nosocomial infection from unsafe blood products and a variety of medical procedures (injections, dental care, endoscopy, surgery etc.) in port medical facilities

- Unprotected sexual intercourse

- Piercing and tattooing

Additional steps can also be taken that include:

- the use of personal protective equipment, for example gloves when administering first aid and medical care on board

- safe disposal of sharps and other medical waste on board

- careful choice of location and type of medical care received ashore if possible

- continuous information on the risks of unprotected commercial or other sex, possibly accompanied by the free availability of condoms on board

These are the responsibility of the ship owners/operators and can reduce the risk of infection with Hepatitis B and C along with HIV and other infections.

The international Trade Federation provides information to seafarers:

https://www.itfseafarers.org/en/health/hepatitis-b

https://www.itfseafarers.org/en/health/hivaids

G.2.4 Hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections occur worldwide with transmission through infected blood, saliva and semen. One third of the world’s population is infected. The majority of acute Hepatitis B infections remain asymptomatic although 30-50% of adults present with an acute illness with jaundice, fever and abdominal pain. The incubation period is usually 45 to 180 days and all individuals who are HbsAg positive are potentially infectious.

Transmission occurs by percutaneous (intravenous, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intradermal) and mucosal exposure to infective body fluids. Major modes of HBV transmission include sexual or close household contact with an infected person, perinatal mother-to-infant transmission, injecting drug use, piercing and tattooing and nosocomial transmission. The case fatality rate is about 1%, but higher in those over 40 years of age. In a small fraction of adults infected with HBV, a chronic illness with severe complications such as liver cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatoma develop after decades.

A recombinant vaccine is available which protects from acute and chronic infection and is recommended by the World Health Organization for at-risk groups and for inclusion in childhood vaccine schedules.

HBV in seafarers

Available studies do not allow estimates if seafaring is a risk factor for Hepatitis B infection.

Differences in population of seafarers mainly reflect the prevalence of Hepatitis B infection in the country of origin and the availability of routine immunization in the home country of the seafarer. As an example: The prevalence of chronic Hepatitis B in the Philippines was 16,7% in the year 2016 (1).

A study of 2072 male United States naval personnel done in 1989 showed that the prevalence of the hepatitis B marker anti-HBc in military personnel was comparable to that in a concurrent survey of the United States civilian population. Presence of anti-HBc was independently associated with age, black or filipino race, foreign birth, a history of sexually transmitted disease and South Pacific / Indian Ocean deployment (2).

A retrospective longitudinal study from a Danish research database containing all seamen who had been employed on Danish ships between 1986 and1993 and the National Registry for Notifiable Diseases found that the standardised incidence ratio for hepatitis B Virus infection among male sailors compared to the general population was 3.2 (95% CI:1.79-4.78). The main mode of transmission was intravenous drug use (3).

Bellis and co-workers in a prevalence study conducted among sailors arriving at the port of Liverpool in the United Kingdom found a 12 % prevalence of the hepatitis B marker anti- Hbc among a study population of 291 sailors. Sailors from Asia had a higher prevalence of seropositivity when compared with colleagues from Western Europe, and North America (4).

A clinic based prevalence study from Spain in 1998 assessed 2348 seafarers attending health clinics who were examined for evidence of hepatitis. Out of the 98 symptomatic cases 50 (2.1% of study population) carried anti- HBc-, signifying contact to hepatitis B Virus during their lifetime (5).

A cross sectional study conducted among 95 Vietnamese civilian and military seafarers and 45 other maritime workers in the city of Haiphong showed that 58% (55/140) persons in the study population were positive for HBsAg and Anti-HBs. The authors concluded that Vietnamese seamen are a high risk group for hepatitis B infection (6).

A survey of 103 seafarers attending a training course for medical care on board in Denmark showed that the seamen responsible for medical care on board in the absence of a medical doctor do have a risk of exposure to blood and body fluids. Over a 10-year period 19 out of 103 persons reported contact with blood, including 4 accidents with needles, 23 persons had been in contact with other body fluids and hence at a potential risk of infection (7).

In Georgia, a nation that supplies a large number of seafarers to the global market, hepatitis B virus infection is assessed as part of the pre-employment exams. It was found that 6.5% of 1165 male Georgian seafarers were tested positive for HBs Antigen (8).

Overall, available studies do not allow estimates to be made to show whether seafaring is associated with a higher risk of hepatitis B infection. The results mainly reflect the epidemiology of hepatitis B infection and availability of routine immunization in the country of origin of the seafarer.

Chronic hepatitis B infection with no signs (clinical and lab studies) of hepatic impairment and a confirmed low level of infectivity should not restrict a seafarers’ fitness to work (9).

If a chronic hepatitis B infection is accidentally detected during the pre-employment exam, the clinician will have to counsel the patient on further diagnostic and treatment options. The urgency of diagnostic and possibly therapeutic requirements depend on factors including liver function and the availability of therapy in the country (10).

All seafarers positive for Hepatitis BsAg are potentially infectious, the level of infectivity varies with the viral load. Chronic Hepatitis B infection with no clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatic impairment and a confirmed low level of infectivity should not restrict a seafarers’ fitness to work. If a chronic Hepatitis B infection is detected incidentally during the pre-employment medical examination (PEME), the clinician will have to counsel the patient on further diagnostic and treatment options. The urgency of diagnostic and possibly therapeutic requirements depends on many factors including liver function and the availability of therapy in the country.

Beyond any doubt first aid and medical in the shipping environment is an occupational risk for hepatitis B infection. Full pre-travel immunisation of all seafarers against Hepatitis B is strongly recommended (3x vaccination against Hepatitis B) if not included in the childhood scheme of the respective country.

(1) Gish RG, Sollano JD Jr, Lapasaran A, Ong JP. Chronic hepatitis B virus in the Philippines. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May;31(5):945-52. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13258. PMID: 26643262.

(2) Hawkins RE, Malone JD, Cloninger LA, Rozmajzl PJ, Lewis D, Butler J, Cross E, Gray S, Hyams KC. Risk of viral hepatitis among military personnel assigned to US Navy ships. J Infect Dis 1992;165:716-719.

(3) Hansen HL, Hansen KG, Andersen PL. Incidence and relative risk for hepatitis A, hepatitis B and tuberculosis and occurrence of malaria among merchant seamen. Scand J Infect Dis 1996;28:107-110.

(4) Bellis MA,Weild AR, Beeching NJ, Syed Q. Sexual behaviour and prevalence of antibodies to HIV and hepatitis B seafarers visiting Liverpool. J Infect 1996;32:73.

(5) Cerdeiras MJ, Fontenla ME, Romero B. Morbilidad por Hepatitis B en la gente del mar. In: Asociacion Medica Espanola de Sanidad Maritima, ed. I. Congreso Nacional de Medicina del Mar. Tarragona, 1, 2 y 3 de noviembre 1990. Santander 1991:85-89.

(6) Duc Lung N, Son, NT, Thuc PV. Preliminary investigation of HBV incidence in the seamen and other maritime workers in Hai Phong City of Viet Nam. In: The Norwegian Association for Maritime Medicine; The Norwegian maritime directorate, eds. The Fourth International Symposium on Maritime Health. Oslo June 21 to 25 1997. Abstracts. Oslo 1997:12-14.

(7) Nilaus S. Medics’ risk of exposure to infection with hepatitis B. In: 9th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Equity in maritime health and safety – development through research, cooperation and education. Book of Abstracts. Esbjerg, Denmark 3-6 June 2007. Poster 1-12.

(8) Tchkonia G, Akhvlediani. HBV spreading among seafarers and humoral immunity indexes of HBsAg carriers. In: 9th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Equity in maritime health and safety – development through research, cooperation and education. Book of Abstracts. Esbjerg, Denmark 3-6 June 2007. Paper 5-2.

(9) International Labour Organization. International Maritime Organization. 2011. Proposed revised Guidelines on the medical examinations of seafarers. ISBN: 978-92-2-125096-8 (print), ISBN: 978-92-2-125097-5 (Web pdf)

(10) Carter T 2013. Handbook for seafarer medical examiners. http://handbook.ncmm.no/index.php/infections-transmitted-in-body-fluids-hepatitis-non-a (last access 1.10.2013

G.2.5 Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS)

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is caused by Human Immunodeficiency Viruses 1 and 2 (HIV 1/2) which damage the immune system and make an affected person more vulnerable to infections and to other diseases such as cancer.

AIDS is recognized to be a major public health problem throughout the world. It is now known that the patterns of the epidemic differ between regions. In some parts of the world, such as North America, Europe or the Philippines it mainly affects certain risk groups such as intravenous drug users, immigrants or homosexuals but is also a threat to the general population. In other parts of the world, such as Central, Eastern and Southern Africa and some countries of the Caribbean it is primarily seen in heterosexuals. Countries and regions such as Eastern Europe, China or India are facing new public health challenges due to HIV.

HIV is present in the majority of body fluids of an infected person. Most infections result from contact with semen and vaginal secretions or blood and blood products from a person infected with the virus. HIV cannot be transmitted through social or workplace contact with an infected person and there are no documented cases of transmission through kissing.

In the last decade, the risk of infections through different sexual practices has been studied in detail, showing that the often cited value of 0.001 transmissions per 1000 contacts represents a lower estimate with a high variability due to transmission cofactors such as circumcision or genital ulcer disease. While the risk of disease transmission is highest in the early stages of infection, treatment of the disease with successful lowering of the viral load is now recognized as a powerful public health tool that reduces the risk of transmission.

Cure of HIV infection is not possible, but effective treatment options for HIV infection have existed for more than a decade and new ones are constantly being introduced. For most persons to whom this treatment is available, HIV has turned from an acute into a chronic condition. This requires life-long adherence to antiviral medication. The infected persons will usually be perfectly well for several years after infection. During this time the CD 4 count, a marker of infection, will decline slowly over the years. However latency time from infection to the point when treatment is needed is highly variable due to genetic factors, exposure to infections and general living conditions. In general, treatment starts when damage to the system has reached a potentially dangerous level. Strict adherence to therapy and close monitoring of side-effects and immune-status by a specialist are essential for a successful outcome.

8.1.5.1 Work related risk of HIV infection in sailors

Mobile transport workers, mainly truck-drivers, played a major role in spreading the disease in Africa and India in the evolving global pandemic. Very early in the epidemic HIV/AIDS affected the community of seafarers. Later analysis of blood samples taken during the course of disease revealed that as early as the 1950´s an English seafarer died of AIDS (1).

Hansen et al estimated the risk of HIV infection in seafarers by an analysis of medical records from the main HIV treatment centres in Denmark. The risk of HIV infection in seafarers was estimated in comparison to the general Danish population up to the end of 1992. The incidence of HIV infection for Danish seafarers was estimated to be 0.000016 cases/person-year. This was eight times higher than in the general Danish population. The authors found that most infections in seafarers were acquired heterosexually early in the epidemic in high-endemicity areas (2).

A study published in 1992 conducted among a sample of 561 Spanish seafarers seeking attention prior to travelling abroad confirmed HIV-1 infection in 4% of seafarers (3).

A questionnaire survey from Croatia performed in Rijeka in 1989 to 1990 demonstrated that seafarers had inadequate knowledge about the routes of HIV transmission and rarely used condoms for protection against HIV infection (4).

2 positive cases of HIV in African seafarers visiting a port in Belgium were identified among 599 sailors in the early nineties (5).

Demissie and co-workers reported 1996 in a cross-sectional study in 260 Ethiopian sailors found an HIV-1 prevalence of 9.6% as assessed by blood-testing (6)

A study from Poland analyzed serological HIV tests from 1992 to 1996. From 26,988 tests performed in seafarers HIV antibodies were detected in 11 seamen and 3 deep-sea fishermen (0.05%) (7).

Bellis and co-workers performed saliva testing for HIV antibodies in 304 sailors whilst in Liverpool, United Kingdom. A 0.33% prevalence of anti-HIV was reported (8).

In the Philippines a questionnaire was handed to seafarers who presented at manning agencies from August 1997 to March 1998. The results showed that 52% of 300 respondents admitted extramarital sexual encounters (9). A 2005 report from the Department of Health of the Philippines, which supplies the largest number of seafarers of any country globally, analysed 2250 HIV positive cases. 745 were Filipino overseas workers including 36% seafarers. The main mode of transmission was sexual (10).

An analysis of the central register of HIV/AIDS infections from Montenegro in 2007 indicated that 15% of the total of 68 notified HIV infected persons in Montenegro were seafarers by profession. It is suggested that there are about 6000 professional seafarers in Montenegro (11).

Local fishing communities have been identified as among the highest-risk groups for HIV infection in countries with high overall rates of HIV/AIDS prevalence, such as Brazil, Cambodia, Congo, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Uganda. Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS stems from the time fishers and fish traders spend away from home, their access to cash income, the ready availability of commercial sex in fishing ports and the sub-cultures of risk taking and hyper-masculinity fishers. There is a concern that fishers, as they get more integrated in the global market may spread HIV to prevalence populations (12,13).

The following risk factors for HIV infection are identified (14):

- decreased or absence of access to HIV information,

- barriers to voluntary testing and counselling,

- likelihood of engaging in risky sexual practices,

- separation from spouses and families,

- alcohol use,

- time spent in high prevalence regions.

In a current review (2020) it was found, that many seafarers had no specific training and only learned about STIs and HIV through media such as television (15).

Recent surveys on HIV prevalence in sailors are not available in the scientific literature.

In the authors experience HIV infection and AIDS are very rare innthe seafaring population. In the cruise ship industry a small number of employees of euripaean, UK or US/Canada origin are HIV positive, all of them are well controlled under antitretroviral therapy and highly informed about their disease and their rights as employees in the maritime industry.

(1) Zhu T, Korber BT, Nahmias AJ, Hooper E, Sharp PM, Ho DD. An African HIV-1 sequence from 1959 and implications for the origin of the epidemic. Nature. 1998 Feb 5;391(6667):594-7. doi: 10.1038/35400. PMID: 9468138.

(2) Hansen HL, Brandt L, Jensen J, Balslev U, Skarphedinsson S, Jørgensen AF, David K, Black FT. HIV infection among seafarers in Denmark. Scand J Inf Dis 1994;26:27-31.

(3) Ollero, M, Merino D, Pujol E, Marquez P, Gimeno A, Angulo C. Tattoos and hepatitis C virus infection. VIII International Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam ,19-24 July 1992. Int Conf AIDS 1992;8:180

(4) Sesar Z, Vlah V, Vukelic M, Cuculic M.Knowledge of seafarers about AIDS problems and their vulnerability to HIV infection. Bull Inst Marit Trop Med Gdynia 1995;46:19-22.

(5) Verhaert P, Damme P, Cleempoel R. Seo-epidemiological study on syphilis, HBV and HIV among seafarers in Antwerp.Proceedings of the second international symposium on maritime health. June 2nd-6th 1993. Antwerpen 1995. p 213-223.

(6) Demissie K, Amre D, Tsega E. HIV-1 infection in relation to educational status, use of hypodermic injections and other risk behaviours in Ethiopian sailors. East Afr Med J. 1996; 73:819-22.

(7) Towianska A, Dabrowski J, Rozlucka E. HIV antibodies in seafarers, fishermen and in other population groups in the Gdansk Region (1993-1996). Bull Inst Marit Trop Med Gdynia 1996;47:67-

(8) Bellis MA,Weild AR, Beeching NJ, Syed Q. Sexual behaviour and prevalence of antibodies to HIV and hepatitis B seafarers visiting Liverpool. J Infect 1996;32:73.

(9) Estrella-Gust DP. Policies and programs on HIV/AIDS. Tripartite paper: Policy and programs on HIV/AIDS. Quezon City: Department of Labor and Employment. Occupational Safety and Health Center. http://www.oshc.dole.gov.ph/page.php?pid=133. Last access August 2013.

(10) Department of Health (DOH), Government of the Philippines. 2005 HIV/AIDS Registry. www.jcie.org. Last access August 2013.

(11) Jovicevic LJ, Vranes-Grujicic M. HIV/AIDS in seafaring population of Montenegro and prevention suggestions. In: 9th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Equity in maritime health and safety – development through research, cooperation and education.Book of Abstracts.Esbjerg, Denmark 3-6 June 2007.Poster 1-11.

(11) Ford K, Chamratrithirong A. Migrant Seafarers and HIV risk in Thai communities. AIDS Education and Prevention, 208(5), 454-463, 2008.

(13) (6) Smolak A. A meta-analysis and systematic review of HIV risk behavior among fishermen. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):282-91. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.824541. Epub 2013 Aug 13. PMID: 23941609.

(14) Nikolic N. AIDS prophylaxis –achievements due to appropriate strategies. Int Marit Health 2011; 62, 3:176-182

(15) Pougnet R, Pougnet L, Dewitte JD, Rousseau C, Gourrier G, Lucas D, Loddé B. Sexually transmitted infections in seafarers: 2020's perspectives based on a literature review from 2000-2020. Int Marit Health. 2020;71(3):166-173. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2020.0030. PMID: 33001427.

8.1.5.2 Employment and HIV/AIDS

The International Labour Organisation has published an “ILO Code of Practice on HIV/AIDS and the World of Work” in 2001 where the organisation advocates for the continuation of employment regardless of HIV status. However, the ship as a work place has always been seen as a special entity due to the limited access to diagnosis and therapy while on board.

Dahl evaluated the workplace policies of cruise ship companies concerning HIV positive crew on ships. He found a variety of practices, about half of the 15 companies responding require pre-sea HIV testing, some to avoid hiring HIV+ seafarers, others to establish HIV as a pre-existing condition or to ensure proper follow up of the HIV infected seafarers (1)

The decision on the fitness of a HIV positive person for duty on board is complex and involves in depth knowledge of the natural course of disease, treatment options and living conditions at sea. The Handbook for Seafarers´Medical Examiners gives detailed advice on the best means for taking decisions on fitness to work at sea (2)

The main concern when taking fitness decisions in relation to HIV infection is the access to medication during travel. Risks to other crew members are negligible if HIV viral is undetectable and standard precautionary measures are observed.

(1) Dahl E. HIV positive Crew on Cruise ships. .11th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Book of Abstracts 2010: page 27.

(2) Guidelines on the medical examinations of seafarers / International Labour Office, Sectoral Activities Programme; International Migration Organization. – Geneva: ILO, 2013 ILO/IMO/JMS/2011/12 ISBN 978-92-2-127462-9 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-127463-6 (web pdf)

Post-exposure prophylaxis with accidental exposure to blood and other fluids

HIV infection can be prevented after a contact with body fluids from an HIV infected person. Drugs effective against HIV must be given as soon as possible after a risk-exposure to the virus. Post-exposure prophylaxis, if taken correctly reduces the risk of infection by 80%.

Exposure may occur from accidental exposure to body fluids during medical care and first aid, but also from unprotected sex. For this reason Anti-HIV medication is now recommended by the WHO to be carried as part of the ship’s medical chest (1).

However, no specific recommendations for the best use of post-exposure prophylaxis in the marine environment have been agreed. Most recommendations have been developed for the health care sector or for high risk sexual encounters (such as commercial sex). The use of post-exposure prophylaxis must remain an individualized decision depending on the specific circumstances. It can be safely assumed that the risk for seafarers providing first-aid on board is lower than for health care workers in high prevalence countries. However, unprotected heterosexual or homosexual commercial sex in a high prevalence country (such as South Africa) justifies post exposure prophylaxis. Post-exposure prophylaxis is no substitute for availability of condoms and preventative messages to seafarers.

General rules for the use of antiretroviral post-exposure therapy in an injury during first aid are:

- Immediately remove as much as possible of the body fluid

- If a high-risk exposure is suspected and no medical advice is available start antiretroviral prophylaxis if possible within 2 hours, otherwise consult a medical specialist before the start of treatment. Starting post-exposure prophylaxis more than 72 hours after exposure is not effective and should not be done. Consult a specialized medical doctor or radio-medical advice as soon as possible for continuation of prophylaxis (typically taken for 30 days).

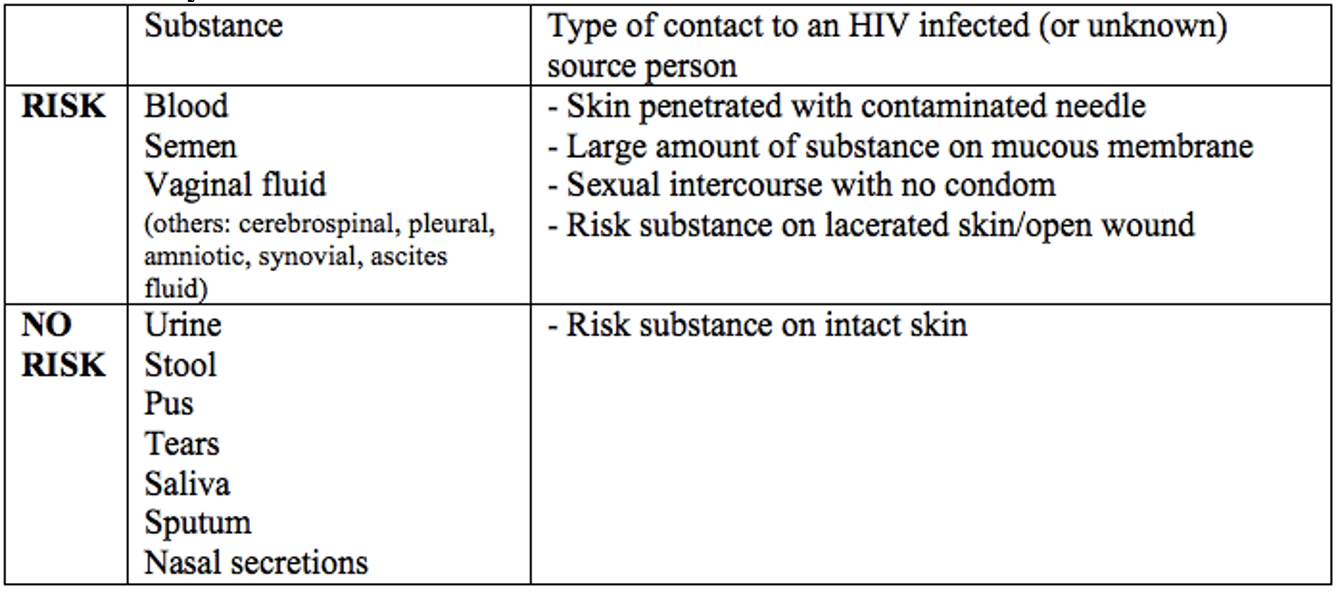

Table 3. Classification of risk of transmission after exposure to HIV

Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases

(1) World Health Organization. International medical guide for ships: including the ship´s medicine chest (IMGS). 3rd edition. Geneva: WHO 2007.

G.2.6 Hepatitis C infection

Hepatitis C virus infection occurs worldwide. Population seroprevalence differs between low – income countries and high income countries.

The main mode of transmission is via reused or shared injections, piercing or tattooing utensils, contaminated blood products or other material contaminated with blood. Spread of disease by sexual intercourse is less likely. Period of communicability is from one or more weeks before onset of symptoms and may persist in most persons indefinitely.

Onset of the disease is usually insidious with anorexia, vague abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting; progression to jaundice is less frequent than with hepatitis B.

Although initial infection may be asymptomatic (more than 90% of cases) or mild, a high percentage of cases (50-80%) develop a chronic infection. About half of those chronically infected persons will eventually develop cirrhosis or cancer of the liver.

No longitudinal studies on the burden of hepatitis C infection in seafarers were identified.

A study published in 1992 conducted among a sample of 561 Spanish seafarers seeking attention prior to travelling abroad confirmed hepatitis C infection in 9% (52/561) of seafarers. Former intravenous drug use and tattooing were found to be independent risk factors for infection with hepatitis C (1).

In a cross sectional study in the United States of n= 2027 Naval military recruits in 1989, the prevalence of hepatitis C virus was found to be 0.4% (9/2072) (2)

A Danish survey among 515 seafarers who sailed in international trade published in 1995 recorded a prevalence of 1.2% antibodies against hepatitis C (3).

In Georgia, Hepatitis C virus infection is routinely assessed as part of the pre-employment exams. It was found that 11.5% (162) of a total of 1400 male Georgian seafarers were anti-HCV positive. Further studies indicated that 157 out of these 162 seafarers had active disease (4).

Medical cards of 270 seamen in Croatia (less than 1% of all approx. 320 000 Croatian seamen) from one general practice in the area of Split were studied in the year 2006 for the presence of hepatitis C infection. Out of 37 test results 8 showed evidence of infection. Documented modes of transmission were intravenous drug use and blood transfusion (5).

Denisenko collected data on Hepatitides among Russian seafarers from 2008 to 2010. Four out of 1630 seafarers were found to suffer from chronic hepatitis C (6).

As with hepatitis B and HIV infection, the prevalence of hepatitis C infection in seafarers is driven by the local epidemiology of the disease. The data from Georgia are conflicting and need further studies.

ILO uses the same principles for hepatitis B and C infection to assess medical fitness in seafarers: With no signs (clinical and lab studies) of hepatic impairment and confirmed low level of infectivity the seafarers’ fitness is not restricted. (7).

No vaccination against hepatitis C is available. Post exposure prophylaxis with IgG is not effective. General control measures for hepatitis B also apply to hepatitis C.

Antiviral medicines can cure more than 95% of persons with hepatitis C infection, but access to diagnosis and treatment is low in many countries due to very high costs of antiviral medication.

(1) Ollero, M, Merino D, Pujol E, Marquez P, Gimeno A, Angulo C. Tattoos and hepatitis C virus infection. VIII International Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam ,19-24 July 1992. Int Conf AIDS 1992;8:180

(2) Hawkins RE, Malone JD, Cloninger LA, Rozmajzl PJ, Lewis D, Butler J, Cross E, Gray S, Hyams KC. Risk of viral hepatitis among military personnel assigned to US Navy ships. J Infect Dis 1992;165:716-719.

(3) Hansen HL, Henrik Andersen PL, Brandt L, Brolos O. Antibodies against hepatitis viruses in merchant seamen. Scand J Infect Dis 1995;27:191-194.

(4) Akhvlediani L, Inaishvili N. The spread of HCV among the seafarers. In: 9th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Equity in maritime health and safety – development through research, cooperation and education. Book of Abstracts.Esbjerg, Denmark 3-6 June 2007.Paper 5-6.

(5) Mulic R, Muslim A, Loncar A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Croatian seamen.In: 9th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Equity in maritime health and safety – development through research, cooperation and education.Book of Abstracts.Esbjerg, Denmark 3-6 June 2007.Paper 5-1.

(6) Denisenko I. Hepatitides amon Russian seafarers sailing under the foreign flag. .11th International Symposium on Maritime Health. Book of Abstracts 2010: page 30.

(7) Guidelines on the medical examinations of seafarers / International Labour Office, Sectoral Activities Programme; International Migration Organization. – Geneva: ILO, 2013 ILO/IMO/JMS/2011/12 ISBN 978-92-2-127462-9 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-127463-6 (web pdf)

G.2.7 Sexually transmitted diseases in seafarers

As indicated above, seafarers have traditionally been seen as a special risk group for acquiring and spreading sexually transmitted diseases.

A literature search did not reveal any recent studies on sexually transmitted diseases known to be of significance in international travel including Chlamydia trachomatis, syphilis, gonorrhea, chancroid, donovanosis, Herpes genitalis. While there is no indication of an increased risk in seafarers the disease(s) can be expected within normal rates depending on regional epidemiology.

The International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN) provides very useful material to educate seafarers on the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/seafarer-health-information-programme/stis-hiv-aids

G.2.8 Haemorrhagic fevers, e.g. Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)

On 8 August 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in accordance with the International Health Regulations (2005).

Since then there have been localized outbreaks ongoing, mostly in the Central Africa. In May 2021 the 12th Ebola outbreak in Africa was declared over A vaccination is available for health-care workers via the World Health Association

Ebola virus disease (EVD), formerly known as Ebola haemorrhagic fever, is a rare but severe, often fatal illness in humans. The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads in the human population through human-to-human transmission. This occurs via direct contact, through broken skin or mucous membranes with the blood or body fluids of a person who is sick with or has died from Ebola, or through contact with objects that have been contaminated with body fluids such as blood, faeces or vomit, from such a person.

People remain infectious as long as their blood contains the virus and the incubation period is 2-21 days. A person infected with Ebola cannot spread the disease until they develop symptoms. Symptoms of EVD can be sudden and include:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Muscle pain

- Headache

- Sore throat

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Rash

- Symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function

- In some cases, both internal and external bleeding (for example, oozing from the gums, or blood in the stools).

The average case fatality rate of EVD is around 50%, ranging from 25 - 90% in past outbreaks. No cases of EVD in seafarers have been reported and there is no risk for seafarers.

The IMO has published advise for ships concerning EVD