CLARA SCHLAICH

G.1.1 Introduction

It has long been recognized that the occurrence of infectious diseases in seafarers is strongly related to working and living at sea. During the current COVID-19 pandemic seafaring was heavily affected not only by the burden of diseases secondary to SARS-COV2 outbreaks on board, but even more so by travel restrictions, strict quarantine measures, lack of access to leisure facilities in ports, general treatment, lack of oxygen, testing and vaccination. Seafarers suffered of mental stress, anxieties and precarious life and family situations.

Maritime physicians need to follow global infectious diseases trends, understand the epidemiological factors affecting infection and transmission on board, the cultural needs of the seafarers and ensure that all regulatory requirements at ports are met.

When advising, health practitioners must keep in mind the features of the workplace, for example, the seafarer’s rank, the ship´s route, flag, size, cargo and the construction of the vessel. Seafarers experience wide variations in living quarters, food, air and water supply. The composition of crew and contact with passengers and with onshore workers also influence the risk of infections. A useful resource to follow global immunization schemes in international seafarers is provided by WHO (1).

The maritime physician needs to be aware that infectious diseases may pose a threat not only to seafarers, passengers, but also to the public health in ports and home countries. Legal notification requirements must be observed. However, risk perceptions may vary widely and be guided by political or economic goals, thus infections control measures often restrict the free movement of seafarers in port areas without appropriate scientific evidence. The focus of the maritime physicians is to protect the seafarer´s health and safety, laid out by international legislation (International Maritime Convention 2006). In doubt, turn to responsible bodies in your port, such as the International Trade Federation (2) or to a port welfare organizations (3).

(1) https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary

(2) https://www.itfseafarers.org/en/your-rights

(3) https://icma.as/

G.1.1.1 Sources of Data

Travel related disease may either result from person-to-person transmission of infectious agents or through vectors such as food, water or mosquitoes on board ships or in ports, as well as from a pre-existing condition. Many, but not all, infectious diseases which have been described in travellers are seen in seafarers as well. This may be due to the fact that more studies are undertaken in travellers than in seafarers but risk patterns may differ.

Equally, the magnitude of infectious disease occurrence in seafarers as an occupational group is ill defined due to several challenges for researchers. The global population of seafarers cannot, by the nature of the profession and organization of the international and national shipping fleet, be described and studied as such. Seafaring includes many different working environments, such as fishing, navy ships, ferries, cargo ships and many others. Also, employers give seafarers contracts with varying durations. Ships under the management of one country may be registered under a different flag and acquire personnel from a crewing agency in another country. Hence there is no single source which can be referred to for information on infectious disease morbidity and mortality for any specific population of seafarers.

G.1.1.2 Common study designs

Common study types concerning infectious diseases in shipping include:

- Longitudinal studies

- medical log books

- surveillance networks

- seafarers national insurance data

- navy registers

- Cross-sectional studies

- pre-employment exams

- data from port medical services or welfare centres

- telemedical consultations

- cross-sectional investigations on board

- Case studies – reviews

- investigations by health authorities

- treatment reports and port doctors

While all of these sources have the potential to improve knowledge about the frequency and prevention of infections in the maritime sector, few have been analysed in any depth.

With a few notable exceptions, no national or international surveillance systems exist to record infectious disease occurrence on ships. Most national or international surveillance systems for infectious diseases do not collect data on professions in general and seafaring in particular. Most studies on infectious diseases in seafarers are prevalence studies in convenient samples, or case and outbreak reports. A further source of bias is the fact that only a few research groups on maritime health exist globally. Most of them are in European countries, for example, the UK, Denmark, Poland and Germany. These traditional maritime nations, while they have active maritime sectors, no longer supply the majority of personnel to the modern shipping industry

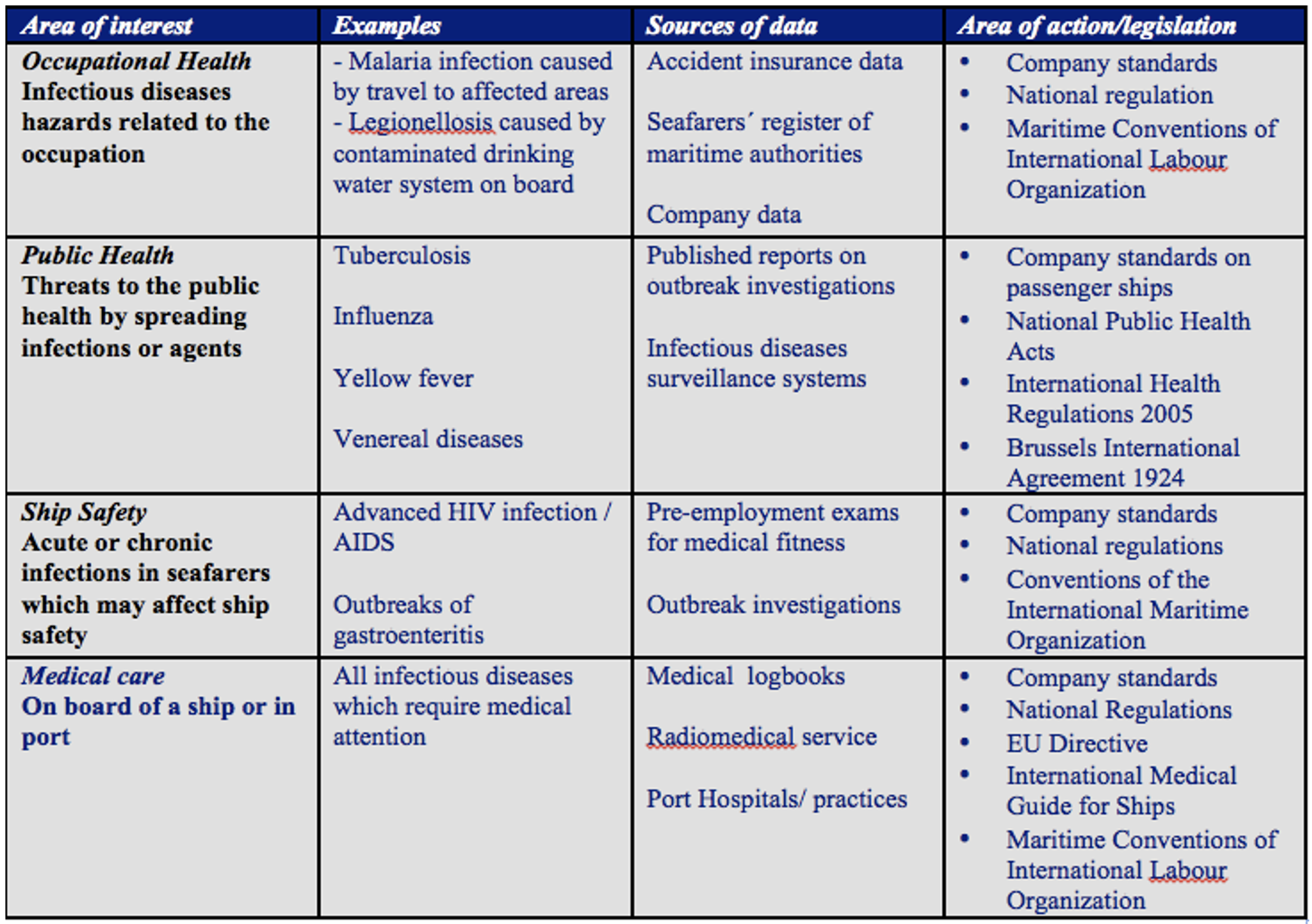

Epidemiological studies are commissioned for a defined purpose. Different interests drive the research and guidelines concerning infections on board of ships. Understanding of the sources of data on infectious diseases in seafarers is needed to draw correct conclusions and give valid advice. While medical care on board and in ports and considerations of ship safety are closely interconnected, research activities also focus on controlling risks to public health from the shipping industry.

Table 1 shows the areas of interest which have driven legislation and research efforts on infectious diseases in seafaring.

G.1.1.3 The magnitude of the problem

The epidemiology, prevention and control of infectious diseases differ substantially in different maritime environments, such as cruise ships, cargo ships, military ships, offshore installations and fishing communities.

Historic events concerning maritime spread of plague, cholera, influenza are well described (1) and led to the introduction of maritime quarantine measures, international sanitary conference and currents laws, such as the 2005 WHO International Health Regulations (2).

During the 2010 IMHA workshop on “Infection on board ships in the 21st century” it was emphasized that important aspects of risk and intervention are different for infectious diseases in the maritime sector and for similar conditions arising ashore (3).

Studies that quantify the current risks of infectious diseases in seafarers as compared to the general population are rare. For HIV, Hepatitis B and C or Hepatitis A the prevalence of the disease in the home country is the strongest predictor for occurrence in seafarers and passengers (4).

Accident insurance data and data from maritime authorities have documented the occurrence of infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, which are commonly recognized as occupational diseases with a relevant travel history or when contact to a case (of tuberculosis) has occurred. Often, these registers underestimate the occurrence of disease due to international crewing practices.

Hansen and co-workers performed a retrospective study based on a national register of all seafarers employed on Danish ships during 1986 to 1993. Infectious diseases were more common among seafarers than in the male Danish population in general. Main causes of death on board of Danish merchant ships were infectious, gastrointestinal, heart diseases and stroke (5).

Also from Denmark, Linda Kaerlev systematically studied time trends in hospital contacts among Danish seafarers and fishermen between 1994 and 2003. She found hospitalization rates for non-officers highest for infectious diseases, fishermen had high hospitalization rates for tuberculosis (15 cases). Alos she described HIV infection among non-officers. (6)

Radiomedical services provide important information on disease activity onboard cargo ships.

Out of 866 cases and 1720 radiomedical contacts in 48 consecutive months from U.S. flagged ships at sea to US emergency medicine physicians for advice, 48% of cases were medical, 14% were injuries and 2% were purely psychiatric. 15% of the medical cases were due to respiratory infections (7).

Data from the radiomedical service in Sweden from 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2009 demonstrated that 33% of all 1290 consultations concerned infections, most often from the respiratory and digestive system. 71% of seafarers completed treatment on board and no further treatment in port or repatriation were necessary (8).

Schlaich et al. showed in a retrospective study based on medical log-books from merchant ships under German flag that during more than 1.5 million person-days of observation from 2002-2008, nearly one fourth of the visits to the ship’s infirmary were due to communicable diseases (45.8 consultations per 100 person-years) (9).

Navy ships provide important insights on infectious disease prevalence and transmission on board, e.g. outbreaks of food-borne disease, respiratory diseases such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, COVID-19, influenza, tuberculosis, hepatitis A, B and C (10,11,12) and others.

The significance of transmission of gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases in commercial cruise ship is widely recognized for decades. Trough the efforts of the US Vessel Sanitation Program (13) and EU projects such as CDC SHIPSAN ACT, SHIPSAN Trainet and others (14) valide surveillance data are generated and control measures evaluated.

In a 3 year prospective documentation of outbreaks on a cruise ships with 440 passengers and 421 crew members, influenza like illness and acute respiratory illness were the predominant reason for consultation as compared to gastrointestinal disease (15).

The ongoing COVID-10 pandemic is advancing our understanding of respiratory disease transmission on board of ships. Across all types of ships, problems in handling outbreaks resulted from a high number of asymptomatic infections, transportation issues, challenges in communication or limited access to health care (16).

Most currently, a research project “ARMIHN” (Adaptive Resiliency Management in Port) assessed the need to srengthen capacities to act in a mass casualty incident due to an outbreak of infectious diseases on cruise ships in the Port of Hamburg (17).

(1) Carter T. Infections at sea past and present. Int Marit Health. 2011;62(3):157-9. PMID: 22258839.

(2) Hardiman M. The revised International Health Regulations: a framework for global health security. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003 Feb;21(2):207-11. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00294-7. PMID: 12615388.

(3) Carter T. Infection on board ships in the 21st century: overview of IMHA workshop, Singapore 2010. Int Marit Health. 2011;62(3):160-3. PMID: 22258840.

(4) GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204-1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

(5) Hansen HL, Henrik Andersen P, Lillebaek T. Routes of M. tuberculosis transmission among merchant seafarers. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(10):882-7. doi: 10.1080/00365540600740512. PMID: 17008232.

(6) Kaerlev L, Jensen A, Hannerz H. Surveillance of hospital contacts among Danish seafarers and fishermen with focus on skin and infectious diseases-a population-based cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(11):11931-11949. Published 2014 Nov 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph111111931

(7) McKay MP. Maritime health emergencies. Occup Med; 2007 Sep;57(6):453-5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm053. Epub 2007 Jul 25. PMID: 17652345.

(8) Westlund K. Infections onboard ship--analysis of 1290 advice calls to the Radio Medical (RM) doctor in Sweden. Results from 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2009. Int Marit Health. 2011;62(3):191-5. PMID: 22258846.

(9) Schlaich CC, Oldenburg M, Lamshöft MM. Estimating the risk of communicable diseases aboard cargo ships. J Travel Med. 2009 Nov-Dec;16(6):402-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00343.x. PMID: 19930380.

(10) Riddle MS, Smoak BL, Thornton SA, Bresee JS, Faix DJ, Putnam SD. Epidemic infectious gastrointestinal illness aboard U.S. Navy ships deployed to the Middle East during peacetime operations--2000-2001. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006 Feb 25;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-9. PMID: 16504135;

(11) Nir-Paz R. Mycoplasma pneumoniae Outbreaks on Navy Vessels. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 May;48(5):1990; author reply 1990. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00113-10. PMID: 20444984; PMCID: PMC2863942.

(12) Kasper MR, Geibe JR, Sears CL, Riegodedios AJ, Luse T, Von Thun AM, McGinnis MB, Olson N, Houskamp D, Fenequito R, Burgess TH, Armstrong AW, DeLong G, Hawkins RJ, Gillingham BL. An Outbreak of Covid-19 on an Aircraft Carrier. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 17;383(25):2417-2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019375. Epub 2020 Nov 11. PMID: 33176077; PMCID: PMC7675688.

(13) Jenkins KA, Vaughan GH Jr, Rodriguez LO, Freeland A. Acute Gastroenteritis on Cruise Ships - Maritime Illness Database and Reporting System, United States, 2006-2019. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021 Sep 24;70(6):1-19. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7006a1. PMID: 34555008; PMCID: PMC8480991.

(14) Hadjichristodoulou C, Mouchtouri VA, Martinez CV, Nichols G, Riemer T, Rabinina J, Swan C, Pirnat N, Sokolova O, Kostara E, Rachiotis G, Meilicke R, Schlaich C, Bartlett CL, Kremastinou J, Partnership TS. Surveillance and control of communicable diseases related to passenger ships in Europe. Int Marit Health. 2011;62(2):138-47. PMID: 21910118.

(15) Pavli A, Maltezou HC, Papadakis A, Katerelos P, Saroglou G, Tsakris A, Tsiodras S. Respiratory infections and gastrointestinal illness on a cruise ship: A three-year prospective study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016 Jul-Aug;14(4):389-97. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.05.019. Epub 2016 Jun 15. PMID: 27320130.

(16) Kordsmeyer AC, Mojtahedzadeh N, Heidrich J, Militzer K, von Münster T, Belz L, Jensen HJ, Bakir S, Henning E, Heuser J, Klein A, Sproessel N, Ekkernkamp A, Ehlers L, de Boer J, Kleine-Kampmann S, Dirksen-Fischer M, Plenge-Bönig A, Harth V, Oldenburg M. Systematic Review on Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 on Cruise, Navy and Cargo Ships. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 13;18(10):5195. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105195. PMID: 34068311; PMCID: PMC815334

(17) Klein A, Heuser J, Henning E, Sprössel N, Kordsmeyer AC, Oldenburg M, Mojtahedzadeh N, Heidrich J, Militzer KC, Belz L, von Münster T, Harth V, Ehlers L, de Boer J, Kleine-Kampmann S, Boldt M, Dirksen-Fischer M, Haralambiev L, Gümbel D, Ekkernkamp A, Bakir MS. A mass casualty incident of infectious diseases at the port of Hamburg: an analysis of organizational structures and emergency concepts. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2021 Aug 31;16(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12995-021-00324-0. PMID: 34465347; PMCID: PMC8406386.

G.1.1.4 Epidemiology of maritime infectious diseases

There is great diversity in the clinical patterns of different infections and hence the features of individual infections are discussed, by reference to their main modes of transmission.