JON MAGNUS HAGA, KATINKA SVANBERG

D.8.1 Introduction

Maritime search and rescue (SAR) refer to a wide range of medical and logistical measures that aim to prevent loss of health or life in the event of distress at sea.

The nature of SAR operations vary according to geographical and climatic constraints, as well as the availability of SAR assets. SAR operations may take the form a coordinated response, for example, led by a maritime rescue coordination centre (MRCC) and including land-based, airborne and floating assets. It may involve a single responder, for example, from another vessel in the proximity of the individual or unit in distress. Often it is somewhere in between. The ‘search’ of SAR is the effort to locate a person or vessel in distress and the ‘rescue’ includes the operations aimed at retrieving a person or a vessel in distress, providing medical and non-medical assistance and evacuating individuals in need to a place of safety.

Maritime search and rescue is regulated by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Convention on Search and Rescue (SAR convention)[1], the Maritime Labour Convention 2006[2] (MLC) and the United Nations Convention on the Law Of the Sea (UNCLOS)[3] and is the shared responsibility of all seafarers, as well as coastal states. Telemedicine is an integral part of maritime SAR as discussed in Ch. 5.7.

D.8.2 History of search and rescue

The dangers at sea have troubled seafarers and challenged seafaring for as long as man has navigated the seas. Throughout history, shipwrecks have claimed the lives of countless numbers of seafarers and illnesses, disease and malnutrition at sea have claimed the lives of many more.

It has been argued that the dangers faced at sea have promoted a sense of community and a shared understanding between seafarers, that they will come to each other’s assistance in the event of an emergency. In that sense, search and rescue is by no means a new invention.

The Rhodian Sea Laws provide the first written reference to the management of distress at sea. Recorded in 600-800 AD, the law detailed how the lightening of ships by dumping cargo in the event of maritime distress was permissible in the Byzantine empire, and how coming to someone’s rescue would be compensated. Although it should be noted that the primary concern of the law was the value of the cargo, rather than the lives of the seafarers, it may be considered an early precursor to modern day search and rescue at sea.

In the later mediaeval sea laws, including the French Rolls of Oleron in the 1200s and the Wisby Sea Law in the 1500s, a stronger emphasis on wellbeing of seafarers were included, introducing penalties for those harming or plundering a shipwrecked seafarer. Further information on the history of the maritime industry is available in Vol IV.

D.8.3 The modern day legal framework

The first legal obligation to come to a seafarer’s assistance was introduced with the Brussels Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules with Respect to Assistance and Salvage at Sea in 1910. This stated that ‘every master is bound, so far as he can do so without serious danger to his vessel, her crew and her passengers, to render assistance to everybody, even though an enemy, found at sea in danger of being lost’.

Later, in 1974, the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)[4] convention called for the establishment of coastal maritime search and rescue (SAR) services and in 1979, the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue was agreed[5]. It states that ‘Every coastal State shall promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements co-operate with neighbouring States for this purpose.’

Later conventions, have included the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982) and the International Convention on Salvage of 1989[6], the latter replacing the Brussels Convention. These have reaffirmed the shipmaster's duty to render aid in the event of distress, which forms the basis of the modern day search and rescue legal framework.

D.8.4 What is distress at sea?

Distress at sea is a situation in which severe and imminent danger threatens a person or a vessel and immediate assistance is required due to an inadequacy of resources, knowledge, experience, or any combination of these factors. In general, distress situations may be grouped into three categories:

- malfunctioning of the ship, e.g. threats to integrity of the ship, engine failure, flooding and fire

- medical conditions, such as injury or illness

- seafarers falling overboard

The maritime context may influence the urgency of the distress situation. For example, an engine failure occurring close to shore in heavy weather may result in more serious consequences than would the same occurrence on a calm day on the high seas. In reverse, a particular medical condition may be constitute a more serious threat to health when evacuation options are long or access to evacuation assets is unreliable. Thus, situations that may be easily managed ashore may constitute a distress situation at sea, due to limited resources, knowledge, experience or access to external support.

D.8.5 What is maritime search and rescue (SAR)?

Maritime search and rescue (SAR) refers to a wide range of medical and logistical measures that aim to ease or resolve potential or actual distress at sea, and prevent the loss of health and/or the loss of lives. SAR operations include searching for and recovering those who have gone missing, assisting those who are injured or sick and evacuating individuals in needs to a place of safety.

Maritime SAR may draw on all available assets in the area of maritime distress. Assets may include private and public actors including:

- vessels afloat in the area including regular merchant ships, military vessels or designated SAR vessels,

- airborne assets, such as helicopters, airplanes or drones and

- land-based assets, such as the national or regional maritime rescue coordination centres (MRCC) and medical treatment facilities, provisional evacuee reception centres, next of kin information centres, call centres and so forth.

D.8.6 Organisation of SAR services around the world

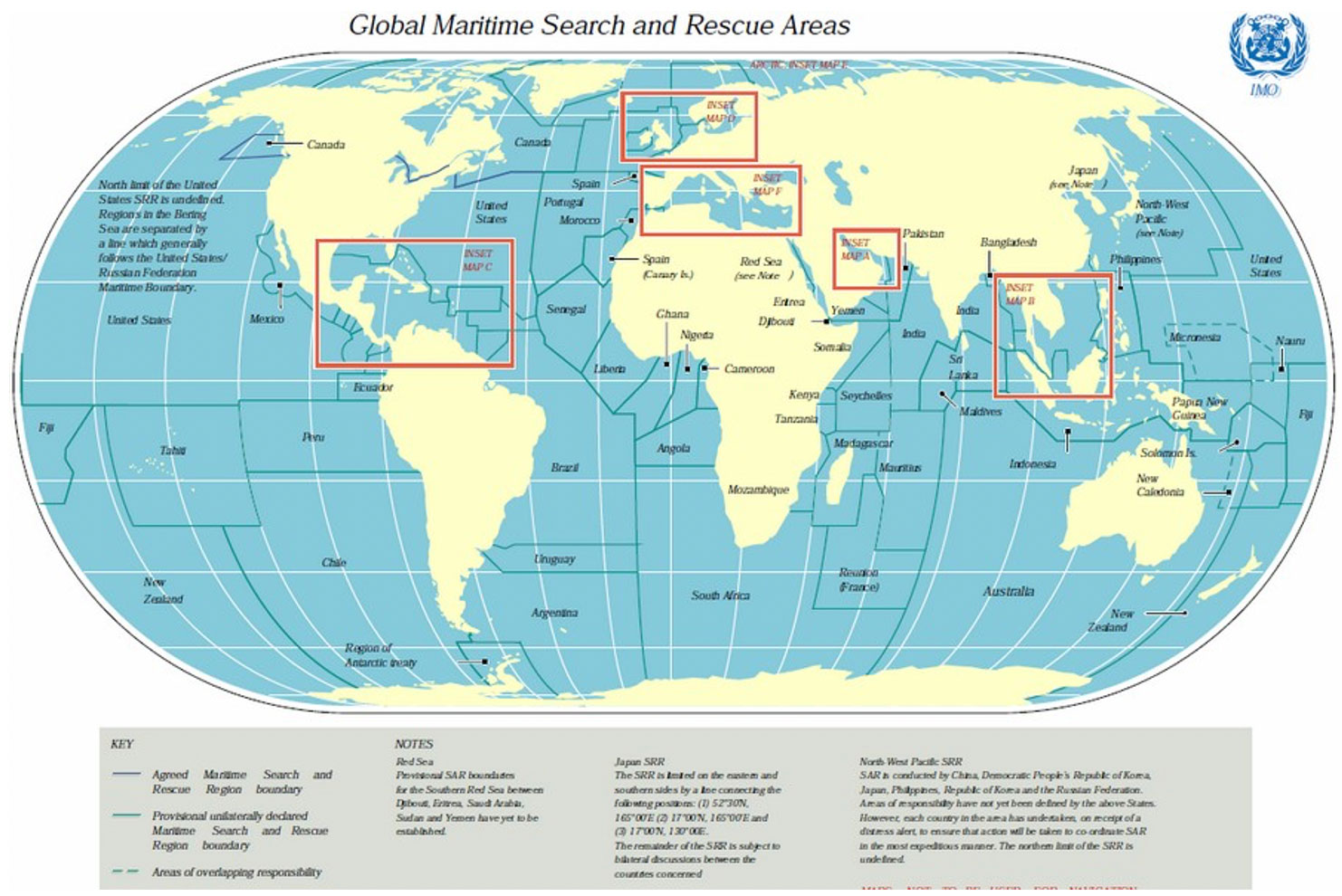

The SAR Convention of 1979 divides the seas into 13 geographical search and rescue areas, in which coastal states are responsible for coordinating search and rescue through a maritime rescue coordination centre (MRCC). Search and rescue is the responsibility of the coastal states and should be offered to the best of their abilities to anyone in distress in the search and rescue areas, regardless of the national origin of the seafarer, the flag of the ship or the circumstances. Nonetheless, despite a legal framework providing for a complete coverage of geographical responsibilities for search and rescue, many sections of the high seas inevitably remain remote. Thus, the SAR-convention is no guarantee that there will be any actual rescue assets available in an area of maritime distress.

Responsibilities of the coastal state

KATINKA SVANBERG

Coastal states and the individual seafarers share responsibilities for search and rescue, according to international law. Every coastal state shall promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service.

Under the SAR Convention, a coastal state shall receive the notification of a person in distress and that coastal state would then assume the lead in the search and rescue mission, usually through its coastguard, together with the flag State of the ship.

The national regulations of several states require medical staff to be included in any search and rescue mission. In addition, a ship that conducts a rescue mission must be prepared for its Medical Officer to provide medical treatment to the survivors and to ensure the provision of hot food and drinks.

D.8.7 Operational challenges

SAR services face many challenges in conduction operations. These include

- Time and climate. These are often critical in survival of distress at sea. When climate is harsh, the time limit for timely rescue may be dramatically reduced. This relationship is often referred to as the “Arctic delta”, and implies that similar circumstances may involve different sense of urgency of in the Arctic than elsewhere. In order to meet the maritime challenges in the Polar Regions, the Polar Code, detailing additional demands for ship construction and survival equipment, was adopted by IMO in 2014[7].

- Political issues. These may also challenge maritime SAR. Piracy and terrorism at sea may hamper maritime SAR efforts. Furthermore, individuals being rescued may be refused entry into a coastal state, the coastal state may not be safe or the coastal state may not be able to provide adequate health services to the seafarer.

- Passenger vessels in distress may prompt mass rescue operations. Mass rescue operations may be defined as operations in which rescue capacities are overwhelmed. Constraints to rescue capacity may relate both to the quantity and quality of rescue assets available and to the number of rescue assets that may operate safely at the same time.

D.8.8 When To Stop Searching

KATINKA SVANBERG

If the missing persons cannot be found during the search, the question of when to stop the search for survivors will arise. There is no definite time limit in which a SAR mission should be completed, only that there should be no hope of survival.[8]

This can lead to conflict between the coastal State and families of the missing who may, understandably, want the search and rescue to continue. Such conflict occurred when a cattle ship, The Gulf Livestock 1, capsized in a typhoon in the East China Sea off the coast of Japan in 2020. The 140 metre vessel, with an international crew of 43, and carrying 6000 cows, issued a distress call on 2 September, when it capsized after losing engine power in the stormy weather. Japan’s coast guard raced to find seafarers but heavy winds and rain from the typhoon slowed the initial rescue operation. Only 3 survivors and one fatality were found. One further casualty died in hospital after being found floating unconscious two days after the rescue mission started. On 9 September Japan decided to end the search with 36 Filipino, 2 New Zealanders and 2 Australians still missing. The decision to stop the search came after several days during no additional survivors or signs of the vessel were spotted. The Australian families pleaded with the Australian government to continue searching, but the Australian government announced that this was a responsibility of the coastal state according to the SAR Convention. After failed attempts at seeking Australian Governmental assistance, family and friends of the two missing Australians launched a private rescue mission funded by donations at a cost of approximately 10 000 AUD per day. Still, after three months, no one was found.[9]

[1] https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Maritime-Search-and-Rescue-(SAR).aspx

[2] https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/maritime-labour-convention/text/WCMS_763684/lang--en/index.htm

[3] https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[4] https://www.imo.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/ConferencesMeetings/Pages/SOLAS.aspx

[5] International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR),1979; Entry into force, 22 June 1985. https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Maritime-Search-and-Rescue-(SAR).aspx

[6] https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Salvage.aspx

[7] https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/Polar-default.aspx

[8]Annette L. Adams, et al., Search Is a Time-Critical Event: When Search and Rescue Missions May Become Futile, Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, Vol 18:2, 2007, p.95 -101, p.100.

5 [9] Emily Consenza, Families will never give up hope of finding missing crew members one month on from Gulf Livestock 1 sinking, The Australian, Oct.9, 2020.