TIM CARTER AND KRIS DE BAERE

B.5.1 What is Port State Control?

The responsibility for ensuring that ships comply with the provisions of national and international rules rests upon the owners, masters and the Flag States. Some Flag States fail to fulfil their commitments as specified in agreed international legal instruments and subsequently some ships may sail in an unsafe condition, threatening the lives of the crew as well as the marine environment.

Port State Control is the process by which a nation exercises authority over foreign ships when those ships are in waters subject to its jurisdiction. Nations that are party to certain international conventions are empowered to verify that the ships of other nations, which are operating in their waters, comply with the obligations set out in those conventions[1]. In addition, a nation may enact its own laws, imposing requirements on foreign ships trading in its waters.

More practically speaking, Port State control is a system of harmonized inspection procedures designed to target sub-standard ships with the main objective being their eventual removal from international trading[2].

ILO states: “The practical consequence of the port state control provisions of Title 5, are that ships of all countries, irrespective of ratification, will be subject to inspection in any country that has ratified the Convention, and to possible detention if they do not meet the minimum standards of the Convention.”

All ships, whether or not their flag state has signed the ILO convention, can be inspected by port state control inspectors and will be treated likewise.

The “Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in Implementing Agreements on Maritime Safety and Protection of the marine Environment “ (MoU 1982) outlines the conditions imposed by the most important international conventions, in a co-ordinated check system[3].

It is important to note that the MoU is an agreement between maritime administrations and not governments. This detaches the memorandum of all political responsibilities and consequences.

B.5.2 Paris Memorandum of Understanding

The origins of port state control in Europe lie in the memorandum of understanding between eight North Sea States signed in The Hague in 1978.

This agreement dealt mainly with the enforcement of shipboard living and working conditions, as required by ILO Convention no. 147. However, just as the Memorandum was about to come into effect, in March 1978, the super tanker, ‘Amoco Cadiz’ grounded off the coast of Brittany, France, resulting in a massive oil spill. This incident caused a strong political and public demand for far more stringent regulations with regard to the safety of shipping.

This pressure resulted in a more comprehensive memorandum that covered

- Safety of life at sea.

- Prevention of pollution by ships.

- Living and working conditions on board ships.

Subsequently, a new, effective instrument known as the Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control was adopted in January 1982. Initially signed by 14 European countries, it entered into operation on 1 July 1982[4].

Since that date, the Paris Memorandum has been amended several times to accommodate new safety and marine environmental requirements from the IMO, as well as other important developments such as the various EU Directives which address marine safety.

Today, the Paris MoU incorporates 27 participating maritime administrations and covers the waters of the coastal European States and the North Atlantic basin from Canada to Europe. The countries are Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

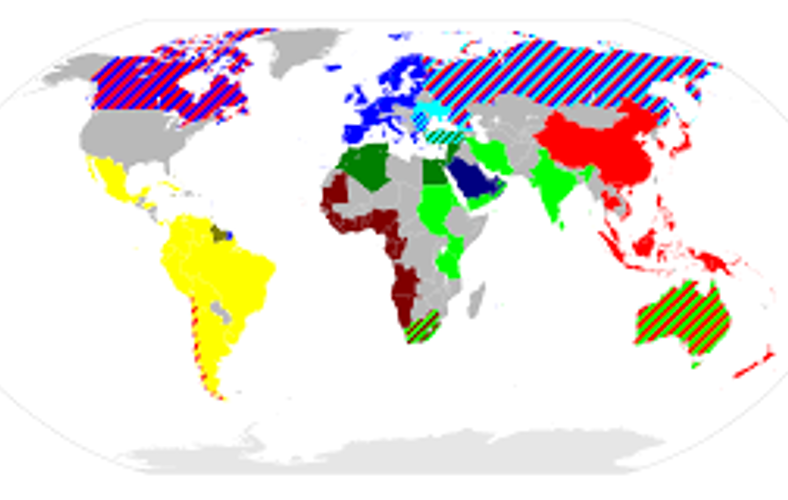

Figure 12.3 2 Country members of Paris MOU 20186

B.5.3 Other Regional MoUs

Worldwide there are currently nine regional agreements on Port State control, with 126 member states.

These regional agreements are:

- The Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control 1982 (Paris MoU) (27 members)

- The Acuerdo De Viña del Mar Agreement on Port State Control 1992 (Latin American Agreement) (13 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Asia-Pacific Region 1993 (Tokyo MoU) (18 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Caribbean Region 1996 (Caribbean MoU) (10 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Mediterranean Region 1997 (Mediterranean MoU) (9 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control For the Indian Ocean Region 1998 (Indian Ocean MoU) (19 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control for the West and Central Africa Region 1999 (Abuja MoU) (23 members)

- The Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Black Sea Region 2000 (Black Sea MoU) (7 members)

- The Riyadh MOU 2004 (6 members)

- Wikipedia Port state Control

Figure 12.3‑3 Regional memoranda of understanding[5].

Signatories to the Paris MOU (blue), Tokyo MOU (red), Indian Ocean MOU (green), Mediterranean MOU (dark green), Acuerdo de Vina del Mar (yellow)[1], Caribbean MOU (olive), Abuja MOU (dark red), Black Sea MOU (cyan) and Riyadh MOU (navy).

The United States Coastguard (USCG), although not a signatory to any of the MoUs, carries out Port State control for compliance with the US Code of Federal Regulations and other International Maritime Conventions.

B.5.4 Port State Control: relevant instruments

The intention of PSC is to ensure compliance with the requirements laid down in the major international maritime conventions. These conventions are called ‘relevant’ instruments in the Memorandum and include the IMO conventions relevant to ship safety and environmental protection, as well as the ILO Maritime Labour Convention 2006.

B.5.5 Basic Principles[6]

Under the Paris MoU, Member States agreed to inspect 25% of the estimated number of individual foreign merchant ships that enter their ports during a 12 month period. This percentage - as well as the relevant instruments - is different in the other regional MoUs. It is very important that these inspections do not cause any economic disadvantage and all possible efforts are made to avoid unnecessary delay of the ship. The inspections are unannounced. In general, the “average” ship will not be inspected within 12 months of a previous inspection in a MoU port, unless there are “clear grounds” for further inspection.

All ships are inspected according to the same guidelines, regardless of which flag they fly.

B.5.6 The Port State Control Officer

A Port State Control Officer (PSCO) carries out Port State control inspections. Also referred to as an Inspector, the PSCO is a properly qualified person, authorized to carry out Port State control inspections in accordance with the relevant MoU, by the Maritime Authority of the Port State by who employs them. . All PSCOs carry an identity card, issued by their maritime authority, and act under its authority.

Various training courses and Seminars for PSCOs are organized by national Maritime Authorities, the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) and the Secretariat of the Paris MoU.

PSCOs board a ship without announcement and start their inspection with a verification of the ship's documents for completeness and validity. Then the PSCO will carry out an expanded inspection of the ship's condition and the required equipment. The Captain will receive an official inspection report consisting of Form A and B. Form A lists the ship's details and the validity of the relevant certificates. Form B shows the list of deficiencies found (if any), with an action code which describes a timeframe for correction of each deficiency. If clear grounds are established that the ship forms a hazard to safety and/or the environment, the PSCO has the right to detain the ship in port until defects have been remedied or even ban the ship from visiting in future (see 12.3.6.3) until the respective deficiencies have been rectified and resurveyed.

The PSC authority will either resurvey using its own inspectors or ask for a survey report from the classification society surveyor (see 12.4) to verify the rectification. In case of a detention or banning the PSC authority has the right to charge for their inspection activities. Any detention or banning has to be reported as soon as possible by the authority to the Flag State, the classification society and the IMO. Data about the inspection and the timeframe for rectification is entered in a computer system used by all members of a regional PSC agreement[7].

B.5.7 Refusal of access or the banning of ships by PSC

There are three reasons for a ship to banned, that is to be refused access to ports in the Paris MoU region:

- When a ship flying the flag of a State on the black list of the Paris MoU has been detained 3 times within a period of 36 months

- When a ship flying the flag of a State on the grey list of the Paris MoU has been detained 3 times within a period of 24 months

- When a ship jumps a detention

- When a ship does not call at the agreed repair yard following a detention

Other MoUs may have slightly different criteria depending on the agreement.

B.5.8 Inspection Efforts by Paris MoU

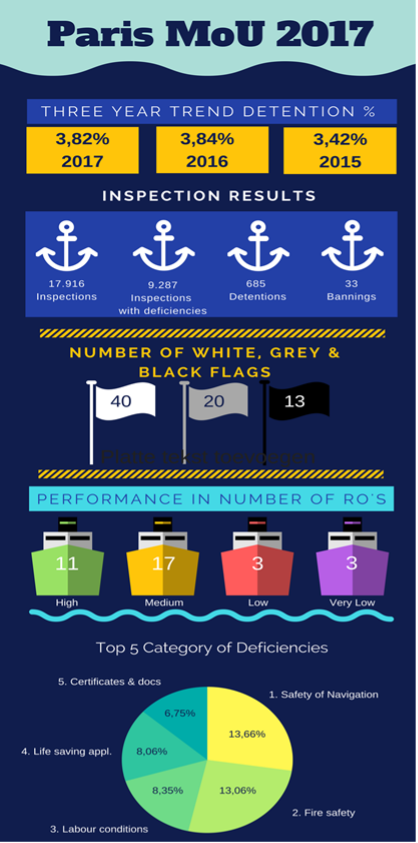

The number of individual ships inspected in the Paris MoU region is increasing. In 2017, the total number of inspections was 17,916. The percentage of ships detained rose from 3.42% in 2015 to 3.84% in 2016 and has stabilised in 2017 at 3.82%.

In 2017, the average number of inspections per ship was 1.17 inspections per year and the average number of deficiencies per inspection was 2.3

All member States reached the 25% inspection commitment in the Memorandum. The individual and joint efforts of Paris MoU members are published in the “annual report”[8].

B.5.9 Ship Targeting

Every day PSCOs select a number of ships for a Port State control inspection throughout the region. To facilitate such selection, the central computer database, known as ‘THETIS’ is consulted for data on ships’ particulars and for the reports of previous inspections carried out within the Paris MoU region.

The THETIS information system, hosted by the European Maritime Safety Agency, informs national PSC authorities which ships are due for an inspection. It also provides data on ships’ particulars and reports of previous inspections carried out within the Paris MoU region.

Each ship in the information system will be attributed a ship risk profile (SRP), in accordance with Annex 7 of the Paris MoU text. This SRP will determine the priority for inspection, the interval between its inspections and the scope of the inspection.

Ships are assigned high, standard or low risk based on generic and historic parameters and calculated according to an agreed protocol.6

A ship’s risk profile is recalculated daily taking into account changes in the more dynamic parameters such as age, the 36 month history and company performance. Recalculation also occurs after every inspection and when the applicable performance tables for flag and recognized organizations are changed[9].

- High Risk Ships (HRS) are ships that meet criteria to a total value of 5 or more weighting points.

- Low Risk Ships (LRS) are ships that meet all the criteria of the Low Risk Parameters and have had at least one inspection in the previous 36 months.

- Standard Risk Ships (SRS) are ships that are neither HRS nor LRS.

Every selected ship has to pass at least an initial inspection. This includes a check of the relevant certification and documentation of the ship and its crew, as well as a check of the overall condition of the ship including the bridge, the accommodation, the main deck and the engine room. A “paper check” alone is not sufficient.

If “clear grounds” are assessed, as defined in the Paris MoU, a more detailed inspection will be carried out. Further assessments are then carried out at intervals dependant on the ship’s risk profile.

B.5.10 Deficiencies, Detentions and Rectifications[10]

The PSCO will exercise professional judgment in determining whether to detain the ship until the deficiencies are rectified or to allow it to sail with certain deficiencies without unreasonable danger to safety, health, or the environment, having regard to the particular circumstances of the intended voyage.

During inspection the PSCO will further assess whether the ship and/or crew is able to:

- navigate safely throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- safely handle, carry and monitor the condition of the cargo throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- operate the engine room safely throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- maintain proper propulsion and steering throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- fight fires effectively in any part of the ship if necessary during the forthcoming voyage;

- abandon ship speedily and safely and effect rescue if necessary during the forthcoming voyage;

- prevent pollution of the environment throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- maintain adequate stability throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- maintain adequate watertight integrity throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- communicate in distress situations if necessary during the forthcoming voyage;

- provide safe and healthy conditions on board throughout the forthcoming voyage;

- provide the maximum of information in case of accident (as provided by the voyage data recorder).

If the result of any of these assessments is negative, taking into account all deficiencies found, the ship will be detained. A combination of deficiencies of a less serious nature may also warrant the detention of the ship.

For further details on the detention of ships and the causal deficiencies, please consult the Paris MOU website and more exactly the document “Guidance on Detention and Action Taken”[11]

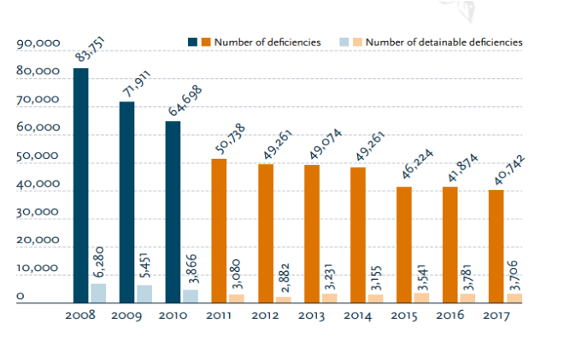

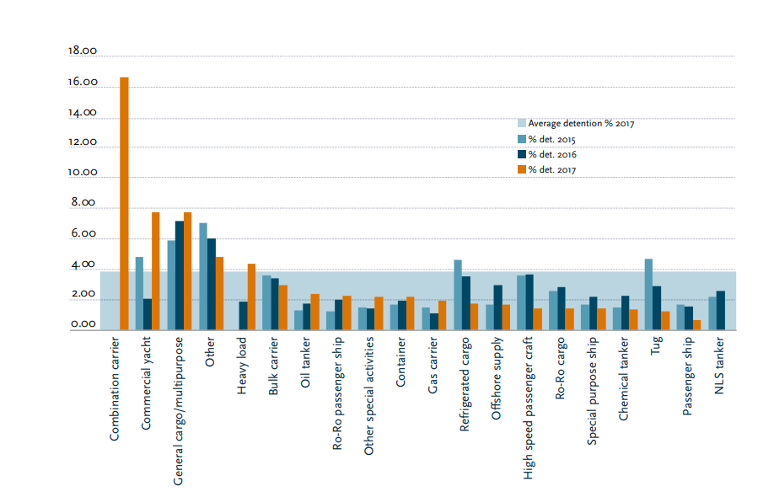

B.5.11 Does the Port State Control System work?

The Paris MoU annual reports demonstrate a steady decrease in the number of deficiencies and detentions found over recent years. In 2017, the detention rate for combination carriers, commercial yachts, general cargo & multi-purpose ships and heavy lift ships was above average. The other ship types have lower detention rates. For more details, the annual MoU reports can be consulted.[12]

Figure 12.3‑11 Paris MoU infographics 19

Major Deficiencies 2017

Figure 12.3‑12 Detention rate per ship type 2015- 2017 12

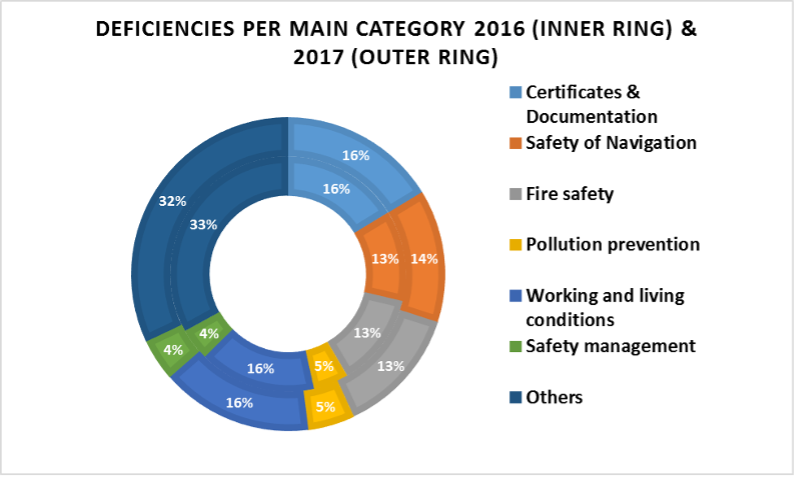

Figure 12.3‑13 Deficiencies per category. 12

B.5.12 The “medical” inspection by PSC officers

The “medical” inspection of ships by the PSCO is based on 2 legal instruments, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) and the ILO convention No 147[13].

Besides the improvement of the safety of life at sea and the prevention of the pollution by ships, the improvement of the working and living conditions on board ships is mentioned as a third objective.

The ILO convention is more specific and prescribes a set of standards relating to the minimum age and the medical examination of seafarers, the prevention of accidents, social security, shipboard conditions of employment and living arrangements to be observed in merchant shipping registered under any signatory flag state. ILO also includes the officer’s STCW certificates of competence.

Any Port State Control inspection starts with the verification of the documents on board the ship. These documents include, amongst others, the certificates of medical fitness of the crew, vaccination lists, de-ratting certificate and the certificate of yearly inspection of the medicine chest and medical equipment.

As part of the inspection of the ship, special attention is given to the condition and use of the shipboard hospital, state and settings of the refrigerators and deep freezers, the hygienic condition of the galley and the condition of the sanitary provisions.

The PCSO thoroughly checks all deficiencies regarding conditions on board and takes action as deemed appropriate. If necessary, the ship will be detained until appropriate corrective action is taken.

The introduction of a “maritime labour certificate” (MLC) enhances the inspection of ships. Issued by the Flag State, or its recognised organisation, this certificate verifies that labour conditions on board comply with national legislation. It will have a validity of 5 years and identifies the “ship-owner” as responsible to satisfy the obligations of the Convention.

A second certificate, a declaration of maritime labour compliance, covers the national law and the owners plan for implementing 14 areas of standards regarding

- minimum age

- medical certification

- qualifications of seafarers

- seafarer employment agreements

- use of a recruitment and placement services

- hours of work or rest

- manning levels

- accommodation

- on board recreational facilities

- food and catering

- health and safety and accident prevention

- on board medical care

- on-board complaint procedures

- the payment of wages.

Port State Control is central to verifying compliance with the 2006 MLC. The possession of the Maritime Labour Certificate and the Declaration of Maritime Labour Compliance will be prima facie evidence of such compliance.

A more detailed inspection is conducted if there are “clear grounds” or “reasonable grounds” for suspecting that the ship has been re-flagged to avoid compliance or there are complaints alleging non-conformance. Non-conformities with the relevant international conventions may result in detention.

B.5.13 References

1. International Chamber of Shipping, ICS, Key facts, overview of international shipping industry. Available from: http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts [accessed August 2018].

2. European Maritime safety Agency, EMSA, The world merchant fleet in 2016, Statistics from Equasis. Available from: http://www.emsa.europa.eu/ [accessed August 2018]

3. European Maritime safety Agency, EMSA, The world merchant fleet in 2013, Statistics from Equasis. Available from: http://www.emsa.europa.eu/ [accessed August 2018]

4. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD, review of maritime transport 2011. Available from: http://unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2011_en.pdf [accessed May 2012].

5. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea III, UNCLOS III, UN, London, 1973, art 91, 92, 94 and 97. Available from: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf [accessed August 2018]

6. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: www.parisMoU.org [accessed August 2018]

7. Greenaway C, Port State Control – A guide for members, London, Thomas Miller and Co, 1998.

8. Somers E, Inleiding tot het internationaal zeerecht, Universiteit Antwerpen, 2004.

9. Oya Özçayı, Z, The impact of Caspian oil and gas development on Turkey and challenges facing the Turkish straits, The Marmara Hotel, Istanbul, 2001.

10. Port State Control. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_State_Control , [Accessed August 2018].

11. UK P&I Club. Available from:http://www.ukpandi.com/ [Accessed August 2018].

12. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU, Annual report 2017. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/2017-paris-MoU-annual-report-%E2%80%9Csafeguarding-responsible-and-sustainable-shipping%E2%80%9D [Accessed August 2018]

13. Det Norske Veritas, DNV, The Paris MoU New Inspection Regime, Hovik, 2010.

14. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU, Explanatory note – “White”, “Grey” and “Black List”. Available from:

https://www.parisMoU.org/system/files/Explanatory%20Notes%20Annual_0.pdf [Accessed August 2018]

15. Mikhail Perepelkin, Sabine Knapp, German Perepelkin, Michiel de Pooter, A method to measure flag performance for the shipping industry, 2009.

16. Pietro del Rosso, Port State Control, unpublished course, I.I.S.S. “Amerigo Vespucci” – Molfetta – Italy & Mediterranean Training Center Ltd, SD.

17. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/sites/default/files/Information%20on%20detention%20and%20action%20taken.pdf [Accessed August 2018]

18. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/sites/default/files/Information%20on%20detention%20and%20action%20taken.pdf [Accessed August 2018]

19. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parismou.org/infographic-paris-mou-annual-2017 [Accessed August 2018]

20. International Labor Organization, ILO. Available from: www.ilo.org [Accessed August 2018].

21. Ludwiczak J, Marine Labor Convention INTERTANKO North American Panel Meeting, Stamford CT - 20 March 2006.

22. World Health Organization, WHO. Available from: www.who.int [Accessed August 2018].

23. STCW convention, IMO. Available from: www.IMO.org [Accessed August 2018]

24. International Labor Organisation, ILO. Available from: www.ilo.org [Accessed August 2018)

25. Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parismou.org/inspections-risk/library-faq/banning [Accessed August 2018]

[1] Greenaway C, Port State Control – A guide for members, London, Thomas Miller and Co, 1998.

[2] European Maritime safety Agency, EMSA, The world merchant fleet in 2016, Statistics from Equasis. Available from: http://www.emsa.europa.eu/ [accessed August 2018]

[3] Somers E, Inleiding tot het internationaal zeerecht, Universiteit Antwerpen, 2004

[4] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: www.parisMoU.org [accessed August 2018]

[5] Port State Control. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_State_Control , [Accessed August 2018].

[6] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: www.parisMoU.org [accessed August 2018]

[7] UK P&I Club. Available from:http://www.ukpandi.com/ [Accessed August 2018].

[8] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU, Annual report 2017. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/2017-paris-MoU-annual-report-%E2%80%9Csafeguarding-responsible-and-sustainable-shipping%E2%80%9D [Accessed August 2018]

[9] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD, review of maritime transport 2011. Available from: http://unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2011_en.pdf [accessed May 2012].

[10] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/sites/default/files/Information%20on%20detention%20and%20action%20taken.pdf [Accessed August 2018]

[11] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/sites/default/files/Information%20on%20detention%20and%20action%20taken.pdf [Accessed August 2018]

[12] Paris Memorandum of Understanding, Paris MoU, Annual report 2017. Available from: https://www.parisMoU.org/2017-paris-MoU-annual-report-%E2%80%9Csafeguarding-responsible-and-sustainable-shipping%E2%80%9D [Accessed August 2018]

[13] Merchant Shipping (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1976 (No. 147), revised by the MLC 2006.