CHRISTOPHER PETRIE

H.10.1 Introduction

A ship and its crew do not normally carry uninvited guests. Merchant vessels sail the world’s oceans in a distinctly self-contained and self-sufficient environment, where routine and procedure are usual. There are, however, occasions when the traditional seafaring life can be interrupted and the crew forced to respond to urgent, sometimes life-threatening situations at sea. Different scenarios include stowaways, refugees, migrants and persons saved at sea. Each has its own distinct set of challenges and responsibilities for the crew.

Stowaways

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) defines a stowaway as:

"A person who is secreted on a ship, or in cargo which is subsequently loaded on the ship, without the consent of the shipowner or the Master or any other responsible person and who is detected on board the ship after it has departed from a port, or in the cargo while unloading it in the port of arrival and is reported as a stowaway by the master to the appropriate authorities".

The IMO Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic, (FAL Convention) of 1965 addresses the issues surrounding the prevention of stowaways in port areas and the repatriation of stowaways once discovered. The IMO has continued to raise awareness of the humanitarian, safety and security problems associated with stowaways.

At the review of the Convention in 2018, the IMO stated: ‘The FAL Convention sets out clear ship and port preventive measures and recommended practices on the treatment of stowaways while on board and disembarkation and return of a stowaway. Taking into account that incidents of stowaways represent a serious problem for the shipping industry, and that no signs of improvements have been seen regarding the reduction of stowaway cases, the Organization strongly encourages Member States to fully implement the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), chapter XI-2 on measures to enhance maritime security, and the ISPS Code, which also contain clear specifications on access control and security measures for port facilities and ships.

However, the language of both the FAL and SOLAS Conventions is more recommendatory than obligatory. In practice, each nation-state enforces its own rules and regulations when responding to stowaways, their disembarkation and eventual repatriation. Thus, the vessel’s obligations will vary from country to country. Experienced ship owners, have developed excellent routines for responding to stowaway situations, particularly when their vessels are trading in Africa and the expectation is that all stowaways are to be treated humanely and according to UN/IMO standards.

Refugees and Migrants

The United Nations defines a refugee as

“someone who, due to fear of persecution for reasons of race, nationality, political beliefs or other similar factors, is unable or does not want to stay in the country where he is and wishes to move to a new country.”

The plight of refugees world-wide is precarious at best and when refugees take to the sea the risk factors multiply significantly. Under the time honoured traditions of seafaring and as set out under Article 98 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982, all merchant ships have a duty to assist those in peril. This is reinforced by three additional conventions administered by the IMO:

- The International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, 1979;

- The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974; and

- The Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic, 1965.

As recent events in the Mediterranean have shown merchant shipping is exposed to many such complex and costly rescue operations involving the safety and security of the ship and its crew. This often includes the immediate medical treatment of the additional persons taken on board.

As noted by the IMO:

A ship should not be subject to undue delay, financial burden or other related difficulties after assisting persons at sea; therefore coastal States should relieve the ship as soon as practicable.

Normally, any Search And Rescue (SAR) co-ordination that takes place between an assisting ship and any coastal State(s) should be handled via the responsible Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC).

Each RCC should have effective plans of operation and arrangements (interagency or international plans and agreements if appropriate) in place for responding to all types of SAR situations.

There is no formal definition of an international migrant althoughthere is general agreement that it is someone who changes their country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal status. Migrants are often found alongside refugees and the industry continues to struggle with the problem of sea-borne migrants.

Persons Saved at Sea

The IMO defines a person saved at sea as

“any person who is neither a stowaway nor a refugee, but who requires urgent life-saving and/or medical attention.”

The classic example is an injured or seriously ill fisher who cannot be attended to on a poorly equipped fishing vessel at sea, far from shore, or a lone yachtsman in distress in the middle of one of the oceans. A radio distress message will be put out and any larger, better equipped vessel in proximity will be called upon to alter course and attempt a rescue.

These cases often require urgent medical care that may be provided on board a larger ship, at least initially and in conjunction with Telemedical Assistance Services (TMAS). In these situations, the vessel will prepare for the patient and contact a chosen telemedicine provider to guide them through the response. Telemedicine plays an important role in minimizing the risk of death or permanent disability. Such persons do not usually have additional needs, nor pose a threat to the ship or people on board and are not considered further here.

H.10.2 Stowaways

Trends and routes

There are certain geographical regions which are more high risk than others. Continental Africa poses the biggest challenge, followed by Central America, Colombia, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. When migrant camps have closed within Europe, there has been an increase in stowaways emanating from European ports, such as in Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain.

Vessels used

Stowaways are mostly found on board bulk, container, general cargo vessels and car carriers.

Who are the stowaways

As most stowaways embark vessels in various African ports, the majority are of African origin, followed by Syrians and Albanians. They tend to board ships that are heading westwards

Management on board

Security on board

This is particularly important in stowaway cases. By nature, stowaways dislike being caught, - at least until the vessel is two or three days sailing time from the port where they hid aboard.

When discovered most stowaways hope that the vessel will continue on its voyage to the next port of call. However, many ships turn around and head back to the port of embarkation because of the legal problems associated with trying to disembark undocumented persons in ports around the world.

When stowaways are told they are being returned to the same port in which they gained access to the vessel, they can become violent. In these situations, the Master’s duty to maintain the safety and security of the vessel and its crew is the most important consideration. Therefore stowaways can be locked in a room where they are provided with only basic humanitarian assistance. This could potentially limit the ability of the officer responsible for medical care on board to treat the stowaways until the vessel reaches the return port.

Medical care

Stowaways may require medical attention on the ship and hospitalization at the port of disembarkation. These costs are borne by the ship owner, there being no one else to step in and assume responsibility for the stowaway.

Repatriation

If the ship does not return to the country of origin, the stowaway will need to be repatriated once the ship has docked in another port. Again, the costs of repatriation are borne by the ship owner including the cost of an airfare (with security escorts). It also includes costs and expenses in guarding and processing the individuals through normal immigration channels as well as fines attributed to the vessel for landing the stowaway.

These costs and expenses, subject to certain conditions, are covered under the vessel’s P&I insurance policy. Further information is available in Ch. 5.13.

H.10.3 Refugees and other migrants

TORDIS MYRSETH

Trends and routes

The phenomenon of people traveling the seas in search of refuge, safety, or simply better economic conditions is not new. Large scale departures of people often follow crises and conflicts in their home countries. Recently, international attention has focused on the movement of Somalis and Ethiopians across the Gulf of Aden and, after the Libya crisis, an outflow of people from North Africa to Europe. These days, the conflict in Syria continues to be by far the biggest driver of migration, followed, in terms of the number of people, by Eritrea and Kongo. Many migrants make their way by land, but the vast majority arrive by sea and irregular maritime movements are, independent of major crises, a reality in all regions of the world. People smuggling has become a large industry, and people smuggling networks earn huge sums from their criminal activities. Most of the profits are used to fund other illicit undertakings, such as illegal drugs and weapons. The networks will always adapt to where there is a need and even though the migrant flow varies, the networks are established and will not disappear.

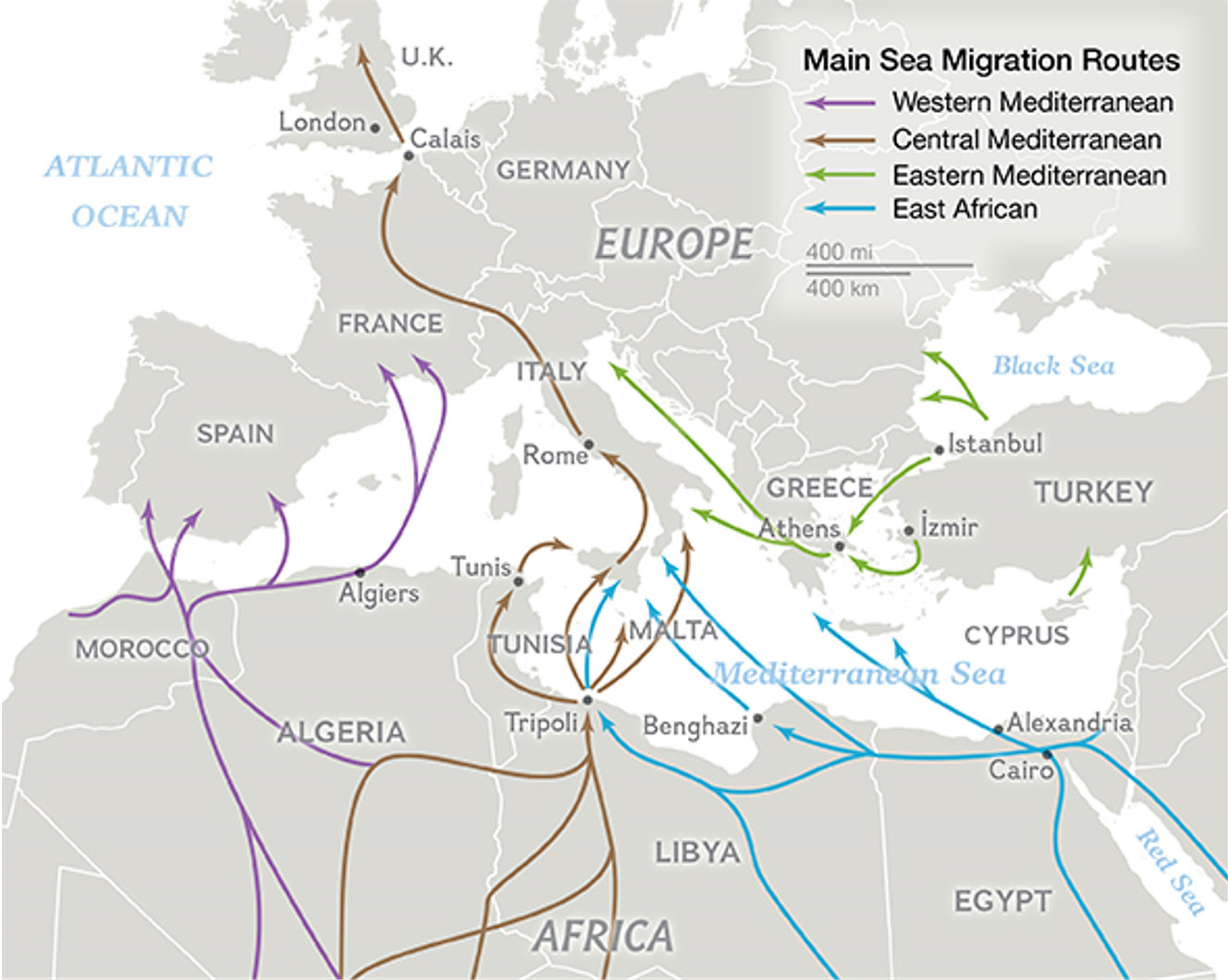

The Mediterranean Routes

The main sea migration routes towards Europe (1).

The two most commonly used routes to enter Europe are the relatively short voyage from Turkey to Greece, known as the Eastern Mediterranean Route, and the longer route from Libya to Italy, known as the Central Mediterranean route.

These routes have been the entry points to the European Union (EU) with the largest migration pressure. In 2015, more than 1 million immigrants arrived on the Greek and Italian shores. This number has decreased substantially, and in 2020 the number was down to 95000 (2).

The Eastern route

The Horn of Africa, Saudi Arabia and Yemen (3).

In recent years, the route between Africa and Yemen has become the busiest maritime migration route on earth. This so-called Eastern route has reported more crossings than the Mediterranean routes for two years in a row. In 2019 most of the migrants arrived at Yemen`s southern coast from Somalia, but a large amount also departed from Djibouti (4). Over 138 000 people crossed the Gulf of Aden towards the Arabian Peninsula in 2019, which is approximately 11500 every month. The majority were of Ethiopian nationality (4).

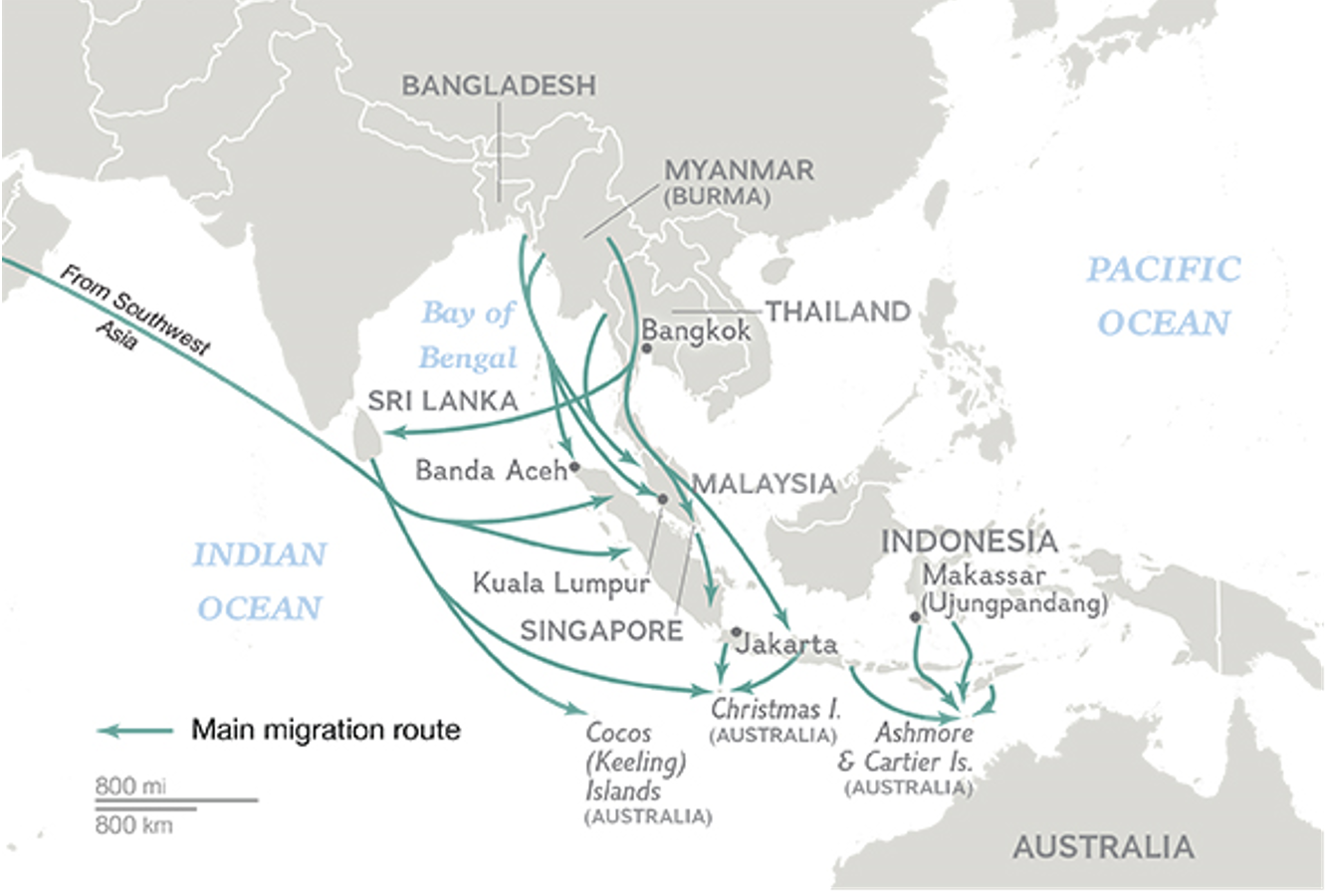

The southeast Asian route

Various migrant routes in southeast Asia (1).

Ongoing and long-lasting conflicts in Myanmar have forced hundreds of thousands to flee in recent years, heading for other southeast Asian nations. Still the numbers of migrants reported to have travelled by sea through the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea was only about 1600 between January 2018 and June 2019 (5). The movements take place manly outside of the monsoon season of June- September, when rough seas, heavy rain or storms are common, heading southeast towards Malaysia and Thailand (5).

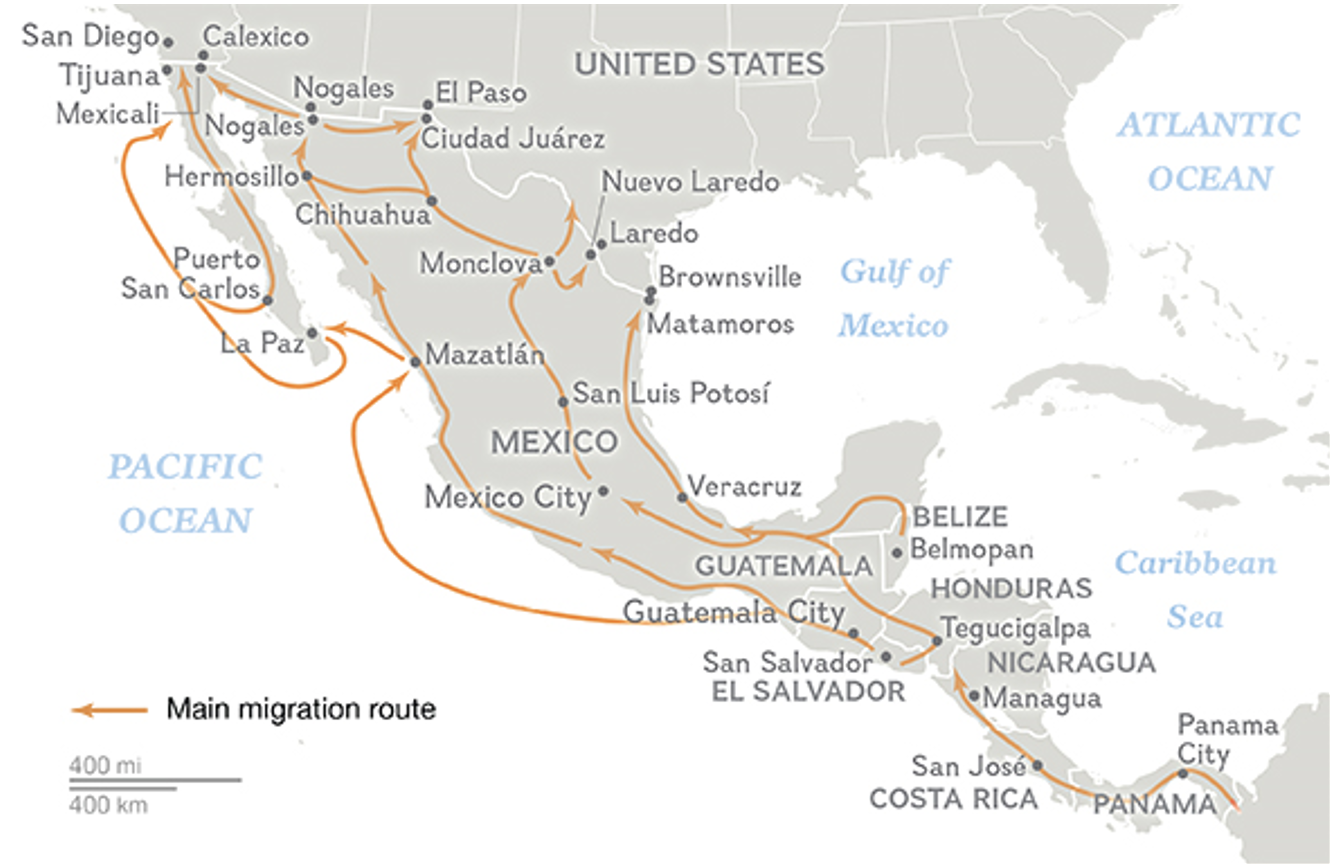

The Central American route

Migrant routes towards the USA (1)

Cross-border smuggling at sea towards the USA is a well-known phenomenon. These routes carry residents from far beyond Mexico, including people from China and Yemen as well as countries in South and Central America (6). Although the number of migrants at sea is nowhere near the same heights as the sea-routes from Africa and over the Mediterranean Sea, it is increasing, due to stricter land-border enforcement on the border between Mexico and the USA. The fact that migrants who apply for asylum in the USA have to stay in Mexico while the application is being processed, may cause even more migrants to attempt to reach the USA through sea-routes without crossing Mexican territories.

The exact death toll for any of these migration routes around the world will probably never be known, as some of the vessels used by the migrants disappear without trace, and there is no registration of how many are on board each vessel.

Type of vessels used

The form of transportation varies. Most migrants travel in flimsy rubber dinghies or wooden boats of various sizes. The boats are in poor condition, overcrowded, and seldom suitable for the voyage. The engines are often deliberately supplied with too little fuel to reach the planned destination, as the smuggling industry experience is that most of the migrant boats are detected and the people taken onto civilian or boarder control vessels, or vessels from non-governmental organizations. Other, even smaller boats are also used, such as the inflatables intended for beach play.

In many cases, migrants are stowed under deck in large numbers, and suffocate due to a lack of oxygen. They are rarely proper equipped with life jackets, and their swimming skills are also often poor.

Who are the migrants?

The term migrant refers to all people who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum, including people fleeing from war stricken countries as well as people seeking better lives and jobs. They are a heterogeneous group of individuals, with a variety of sociodemographic, geographical, ethnical and cultural backgrounds. This also reflects the range of migrants one can meet in boats in need of help at sea. The route used will often reflect the home country of the migrants, and this also influences their motives for migration.

The Eastern Mediterranean route has been mostly used by Syrians, followed by people from Afghanistan and Iraq. These are typically educated people, often travelling as families. On the central Mediterranean route and Eastern route from Africa, the majority are young men traveling alone. The Asian routes have a higher rate of women and children than routes in other parts of the world (5).

But despite the differences, common to all is that they are travelling in the hope of a better future, and they are willing to risk their lives to get there.

Observation and preparation for assisting migrants at sea

Approaching a boat in need, and the transfer of the migrants on to safe boats/ vessels, is a critical part of the operation to ensure the safety of these people.

When a boat is detected, it is of great importance to observe and seek information as what to expect. Is this an area with security issues? In many cases, the facilitator(s), that is the people smugglers are also on board together with the migrants.

- What is the condition of the boat?

- Is it filled to bursting, and the migrants lack lifejackets?

- Are there signs of organisers/facilitators on board?

For security reasons it is inadvisable to ask too many questions to try to discover who is possibly involved in the smuggling amongst the migrants. There have been cases where smugglers have been involved in shooting incidents to resist arrest. It is best to observe closely and pass relevant information on to the authorities in the port the migrants are transported to.

Approaching with caution is key and one of the main objectives is to avoid panic. Migrants can try to reach the vessel that has come to help, and their swimming skills are often poor. Also, if the migrants move too much the turbulence on the boat can cause it to tip over or be destroyed, resulting in a more complex rescue operation with a large number of casualties.

What to expect

As mentioned above, drowning can be encountered in varying degrees, mass drowning being a worst-case scenario. Another common health challenge is dehydration, depending on how long the migrants have been at sea.

Depending on location and season, hypothermia is also a problem that may arise. Migrants traveling in wintertime, with wet clothes from water that enters or strikes the boat and no possibilities for drying or changing clothes, will get cold. This can also occur in the summer, especially on the shorter routes, where most boats set out at night.

Most irregular maritime movements today are ‘mixed movements’, involving people from different countries. Many have been waiting to set out to sea for a long time, under bad living conditions where diseases spread easily. In addition, spending days crowded on a boat, with no facilities and bad hygiene will increase the spread of diseases. This problem is most relevant on the longer routes, such as the Central Mediterranean route from North Africa to Europe. It is equally important to bear in mind what some of the migrants carry with them in the way of bad experiences from war, flight or long stays in detention camps, and so on. Some can be highly traumatized, and therefore behave irrationally.

Receiving migrants on board the rescuing vessel

There are clear duties under international maritime law, and a longstanding maritime tradition, to assist persons in distress at sea. The 1974 Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, SOLAS, adopted by most nations worldwide, says that any ship becoming aware of persons in distress are obligated to provide assistance, irrespective of their nationality, status or the circumstances in which they are found. Furthermore, the vessel must co-ordinate so that the persons are disembarked in a place of safety as soon as possible (7).

Communication on board

Regardless of the reason people flee/travel, the fear of being returned is great. The migrants need for information must be met. This is especially important when transport time to the port of destination is long. Migrants have different backgrounds, and often have a great problem with confidence. Providing them with information whilst they are on board will create a better sense of peace. Language problems can be a challenge. Some of the migrants may speak English, possibly other languages, and it is useful to identify them and use them, if appropriate, to pass on information end even obtain information.

Security on board

It is an advantage to search the migrants brought on board, if possible. They should not be permitted to bring items such as knives or other sharp objects on board. Other items, such as money or cigarettes, are often a reason for conflicts. It is advisable to try to limit the personal belongings kept in their possession, so they do not have access to things that can be exchanged/traded, or reasons for conflicts, on the crossing. The belongings can be marked with names or numbers, and returned to their owner on disembarkation.

Additional items, like diapers, tampons or extra food/water, should be provided in a way that is not visible to others than those in need, for the same reasons as listed above. If the distance to the nearest safe port is long and takes days, the danger of conflicts between the migrants is greater. Keeping the women and children separated from the men can be expedient, or at least separating families from those travelling alone.

Infection control

Good infection control is essential, to avoid any further infection between the migrants, and transfer of infection to the ship's crew. The use of personal protective equipment such as goggles, gloves and masks are good methods, preferably protective suits if available, and careful disinfection of the areas contaminated. Disinfection of the migrant`s hands and feet when transferring can also limit infection. Dividing the ship into zones, where the migrants have access to a limited area with its own toilet(s) is important. This is to avoid possible infection spreading from the migrants to the crew. The green zone shall be clean, and only accessed by the crew. The red zone is where the migrants are, this also includes a treating area if medical assistance is needed, and a storage area for dead bodies. The red zone can be divided into separate areas for families, women, etc. Between the green and the red zone, a yellow zone should be established. In this zone, the decontamination of all equipment and personnel takes place, after contact with migrants. The intersection between the different zones must be well marked, and preferably physically closed.

Always wear protective equipment when entering the red zones, and keep strict routines going in and out of the different zones. Once the migrants disembark, decontaminate all surfaces and equipment that has had any contact with them.

The ability or capacity of merchant vessels to respond to large numbers on board

Incidents involving large numbers of refugees saved at sea can create severe conditions on board the rescuing ship. Recent events in the Mediterranean, now well documented on television news reports, show that as many as one to two hundred people at a time may require rescue at sea. However the merchant vessels trading in these waters will have stores and medical provisions for only approximately twenty crew members.

To make matters worse, refugees are usually in poor medical condition, having recently gone through enormous mental and physical trauma. Understandably, the ship and its crew will quickly become overwhelmed by the state of affairs on board.

While the officer responsible for medical care may attempt a triage of sorts, he or she cannot be expected to perform any kind of complicated or lengthy medical response. Imperative for the rescuing vessel is simply to safely embark those rescued and head to the nearest port, as ordered by the coast guard or naval authorities.

References

1. National Geographic. Map of Sea routes. [Online] 2021 Jun [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/150919-data-points-refugees-migrants-maps-human-migrations-syria-world.

2. UNHCR. Operational data portal, refugee situation. [Online] 2021 Jun 7 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean.

3. Info Migrants. Trapped in Yemen: African migrants face growing animosity and danger amid COVID-19 outbreak. [Online] 2020 Jun 22 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/25524/trapped-in-yemen-african-migrants-face-growing-animosity-and-danger-amid-covid-19-outbreak.

4. International Organization for Migration (IOM). Journey from Africa to Yemen Remains World’s Busiest Maritime Migration Route. [Online] 2020 Feb 14 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://www.iom.int/news/journey-africa-yemen-remains-worlds-busiest-maritime-migration-route.

5. UNHCR. Refugee Movements in Southeast Asia. [Online] 2019 Jun 30 [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Avaliable from: http://www.unhcr.org.

6. Chivers, C.J. Risking everything to come to America on the open ocean. [Online] 21 Feb 3 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/magazine/customs-border-protection-migrants-pacific-ocean.html.

7. International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Convention for the Safety of Life At Sea (SOLAS). [Online] 1974 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Avaliable from: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201184/volume-1184-I-18961-English.pdf.

H.10.4 The general health of migrants

JON MAGNUS HAGA

The health of migrants may be thought of as a product of their pre-flight health, exposures, and healthcare access, adjusted for their experiences and exposures while underway (1) (2). Some migrants may have fled from fragile states or from war, escaping violence and persecution; others may have fled from famine, lack of clean water, inadequate healthcare, drought or poverty (1) (3) (4) (5).

Their journeys are often lengthy, exhausting and pass through high-endemic areas (6). The migrants may be jammed together in the back of a truck with restricted access to sanitation, clean water, adequate nutrition, healthcare services or suffer from a lack of oxygen when locked up in confined spaces. The mode of transportation may have an impact on health.

The most common health issues reported in migrants in 3 studies (7) (8) (9) are

- Respiratory tract infections/pneumonia

- Dehydration

- Nausea/vomiting/diarrhoea

- Scabies and other skin conditions

- Tuberculosis

- Injuries

- Musculoskeletal pain

Physical and sexual violence, torture, detainment and separation may affect the health of migrants, both pre departure and throughout their journeys. Surveys have shown that at least 50% of migrants (3) and possibly even higher numbers, 94.2% of male and 80.0% of female (5), had experienced physical violence during their journey. In this latter study, more than half of the female, 53.3%, and one in five, 18% of male participants had also experienced sexual violence/rape, of whom 41% reported having suffered this on a daily basis. The exposure of migrants to the potentially traumatic exposures of violence and sexual violence increases the risk of injuries and genitourinary disease, as well as the risk of mental health disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression. This has previously been reported in Syrian migrants settling in Europe (10). Despite being impossible to diagnose or reliably predict in the acute phase, PTSD may surface in the aftermath of traumatic exposures and trouble migrants for years. In addition, migrants may also suffer from a wide range of pre-existing chronic disease, which may or may not be exacerbated by their migration experiences (11).

References

- Adams, K. M., Gardiner, L. D., & Assefi, N. (2004). Healthcare challenges from the developing world: post-immigration refugee medicine. BMJ, 328(7455), 1548-1552. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1548

- Müller, M., Khamis, D., Srivastava, D., Exadaktylos, A. K., & Pfortmueller, C. A. (2018). Understanding refugees' health. Paper presented at the Seminars in neurology.

- d’Angelo, A., Blitz, B., Kofman, E., & Montagna, N. (2017). Mapping refugee reception in the Mediterranean: First report of the evi-med project. In.

- Ben Farhat, J., Blanchet, K., Juul Bjertrup, P., Veizis, A., Perrin, C., Coulborn, R. M., . . . Cohuet, S. (2018). Syrian refugees in Greece: experience with violence, mental health status, and access to information during the journey and while in Greece. BMC Med, 16(1), 40. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1028-4

- Reques, L., Aranda-Fernandez, E., Rolland, C., Grippon, A., Fallet, N., Reboul, C., . . . Luhmann, N. (2020). Episodes of violence suffered by migrants transiting through Libya: a cross-sectional study in "Medecins du Monde's" reception and healthcare centre in Seine-Saint-Denis, France. Confl Health, 14, 12. doi:10.1186/s13031-020-0256-3

- Castelli, F., & Sulis, G. (2017). Migration and infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect, 23(5), 283-289. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.012

- Blitz, B. K., d'Angelo, A., Kofman, E., & Montagna, N. (2017). Health Challenges in Refugee Reception: Dateline Europe 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 14(12). doi:10.3390/ijerph14121484

- Di Meco, E., Di Napoli, A., Amato, L. M., Fortino, A., Costanzo, G., Rossi, A., . . . Petrelli, A. (2018). Infectious and dermatological diseases among arriving migrants on the Italian coasts. Eur J Public Health, 28(5), 910-916. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky126

- Shortall, C. K., Glazik, R., Sornum, A., & Pritchard, C. (2017). On the ferries: the unmet health care needs of transiting refugees in Greece. Int Health, 9(5), 272-280. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihx032

- Peconga, E. K., & Hogh Thogersen, M. (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in adult Syrian refugees: What do we know? Scand J Public Health, 1403494819882137. doi:10.1177/1403494819882137

(11) Trovato, A., Reid, A., Takarinda, K. C., Montaldo, C., Decroo, T., Owiti, P., . . . Di Carlo, S. (2016). Dangerous crossing: demographic and clinical features of rescued sea migrants seen in 2014 at an outpatient clinic at Augusta Harbor, Italy. Confl Health, 10, 14. doi:10.1186/s13031-016-0080-y